Algorithms and Justice

Examining the role of the state in the development and deployment of algorithmic technologies

This post looks at some of the lessons we’ve learned over the last year in our work as part of the Ethics and Governance of AI Initiative, a collaboration of the Berkman Klein Center and the MIT Media Lab.

Image courtesy of Pixabay user blickpixel, CC0

I. Introduction

Our work on “Algorithms and Justice,” as part of the Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Initiative, explores ways in which government institutions are increasingly using artificial intelligence, algorithms, and machine learning technologies in their decisionmaking processes. That work has been defined (loosely) by the following mission statement:

The Algorithms and Justice track explores ways in which government institutions incorporate artificial intelligence, algorithms, and machine learning technologies into their decisionmaking. Our aim is to help the public and private entities that create such tools, state actors that procure and deploy them, and citizens they impact understand how those tools work. We seek to ensure that algorithmic applications are developed and used with an eye toward improving fairness and efficacy without sacrificing values of accountability and transparency. Our work begins with a focus on the United States, while developing more generalizable lessons and best practices.

What follows is a retrospective from this first year of work, describing research modes and outputs and identifying takeaways. Headlines include the following:

- The Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Initiative is well-positioned to be a resource for government actors, who are open to expert engagement and input on difficult technical questions. From legislators to judges to state attorneys general, we were pleased that our efforts at outreach with government officials whose work intersects with the use of autonomous technologies were well-received and that state actors are so interested and open to further guidance and input on these issues.

- Stakeholders with an interest in the use and development of algorithmic tools are demanding clear data and information to inform decisionmaking, and academic initiatives like ours are well-suited to become data clearinghouses. After months carefully designing variables and functionality alongside members of the research and advocacy communities, data collection for the risk assessment database is underway for a launch at the end of summer 2018. Our team is already finding new information about how risk assessments are developed and used and uncovering trends across tools and developers that will be both fodder for significant research and a basis for further data collection efforts.

- Procurement is one component of a larger process and must be considered in its broader context. We often speak of the importance of government procurement officers and of ensuring those responsible for purchasing decisions understand the impact of algorithmic technologies. But, procurement is part of a process that extends beyond the point of purchase or licensing and includes assessment of the technical development process, adoption of implementation guidelines, and rigorous testing and review. We have been researching this larger ecosystem over the past year to provide robust resources and guidance to government such that they can consider the context and make smart systems-level decisions.

- The operations of government actors in this space raise some issues that are unique, novel, and discrete and other issues closely connected to concerns raised by the operations of private and commercial actors. It is impossible to completely divorce consideration of government use of AI, algorithms, and machine learning technologies from a broader conversation about fairness, transparency, equality, inclusion, and justice, as they relate to development and use of these tools in the private sector.

We look ahead with an eye toward maximizing impact and engagement with key constituencies as we move our work forward.

II. Research Map / Methodology

A. Implementing Tools in Government: A Four-Step Process

The Algorithms and Justice research project proceeds from the assumption that use of AI, algorithms, and machine learning technologies by government institutions raises issues that are related to — but warrant consideration separate from — the use of those technologies in the private sector. Early in the course of examining tools that automate (or facilitate) functions of government, it became clear that the use and implementation of such tools is typically characterized by a four-step process.

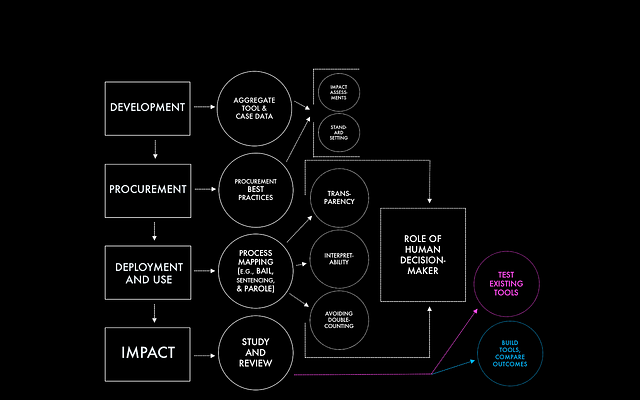

Fig. 1.1 — Research Map and Methodology: Fundamentals of Government Tech Implementation

That process begins with development of a tool to suit a particular set of needs (often — but not always — by a private developer). A government office¹ then procures the tool — acquiring or licensing it. The tool is deployed and used by government officials to carry out their duties. And, finally, the use of the tool (necessarily, by design) has an impact on the population (or a subset thereof) within the relevant jurisdiction.

B. Research and Advocacy

For each element of this four-step process, the Algorithms and Justice team identified gaps that we could fill through research and advocacy. We sought to illuminate existing practices, identify weaknesses, and elevate ethical approaches to government use of automated tools that consider issues such as justice and fairness.

Fig. 1.2 — Research Map and Methodology: Research Interventions

From the beginning, in conversations with stakeholders, we identified a significant demand for data about the development process of tools deployed by government entities throughout the United States and aggregation of available information about tools in one place. The role of government procurement policies and practices and individual procurement officers emerged as key levers for engagement on these issues, and those responsible for procurement too often lacked guidance on best practices when identifying and evaluating tools. Once developed and procured, tools are not used in a vacuum; instead, they are deployed (a) against the backdrop of long-standing legal processes (e.g., in the criminal justice context, legal regimes that govern bail, sentencing, and parole); (b) by individuals (who require rules to govern the role of human decisionmakers and the nature and scope of their interactions with such tools).² Finally, there is significant room for rigorous and long-term study and review of the impact of these tools in government, to assess efficacy and permit modification as needed.³

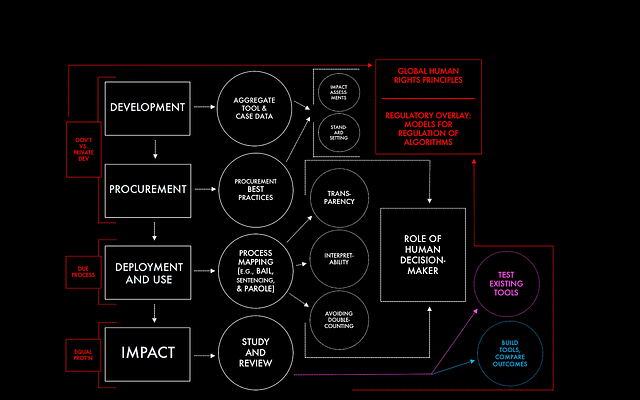

C. Legal and Regulatory Overlay

These various stages in the implementation process raise different clusters of legal issues.

Fig. 1.3 — Research Map and Methodology: Legal and Regulatory Overlay

The development and deployment phases (which are separate in a typical case of private development and public procurement) raise a wide variety of concerns around government contracting, interactions between public officials and private developers, and the nature of procurement processes. The ways in which tools are deployed and used may raise due processconcerns, as criminal defendants and others affected by decisions of government demand appropriate levels of procedural transparency and accountability around decisions that impact their rights. In evaluating impact, one must look at the impact of decisions on constitutionally protected classes of persons to ensure all have the appropriately guaranteed equal protectionunder the law. All of this proceeds in the context of moves toward governance of algorithms and related technologies in other fields, meaning there is room for analogies to the broader range of regulatory models that might be appropriate to address government use of algorithms. And, all of it proceeds against the backdrop of global legal, ethical, and regulatory regimes, including international human rights standards established via treaty obligations.

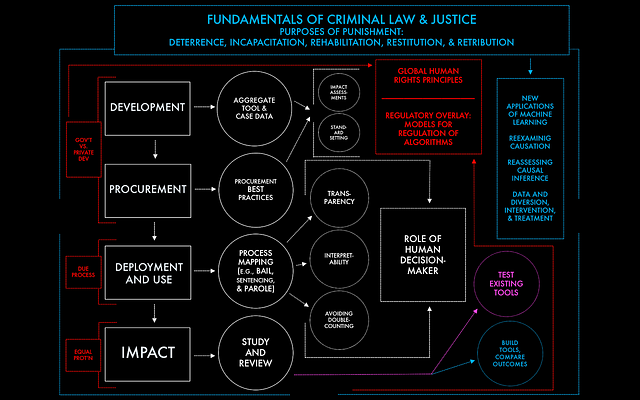

D. Fundamentals of Justice, Alternative Applications of Algorithmic Technologies

Finally, we recognize that this approach is very descriptive. It maps onto existing mechanisms for fostering adoption of tools in government or suggests processes and safeguards that involve relatively subtle tweaks thereto. But, evaluating how the government uses given technologies may require more radical re-imaginings of the role of government and the underlying purpose of the systems we are seeking to automate.

Fig. 1.4 — Research Map and Methodology: Fundamentals of Justice Overlay; Alternative Approaches

One of the first questions that computer scientists ask lawyers when considering use of algorithms generally (and, particularly, to facilitate functions of government) is — for what are we optimizing? In the specific case of criminal justice, these conversations frequently take us back to fundamental questions about the purpose of punishment and the criminal justice system as a whole. In addition, as we entertain questions and flag concerns regarding existing uses of AI and related technologies in government, we must think about new or alternative applications of these technologies. This includes systems-level approaches that go beyond automation of discrete, existing government functions in discrete, existing contexts; interventions that look beyond correlation and more fully incorporate consideration of causation; and applications of technology at different stages in the process of of administering justice or delivering government services beyond merely evaluating risk and the propriety of incarceration. Some of these more expansive investigations of the potential for use of technology by government have been the subject of work by our colleagues at the MIT Media Lab, including Karthik Dinakar, Chelsea Barabas, and Madars Virza and the Media Lab’s “Humanizing AI in Law” or “HAL” initiative. HAL’s work has included examining ways to build and integrate algorithmic systems outside the narrow, often punitive focus we so often see in play today.

III. Key Takeaways

With this framework as our guide, several key takeaways emerged from our work during the first year of the initiative:

- We understood going into this year that procurement represented an important inflection point in the process of implementing algorithmic tools and ensuring they operate in ways that are fair and reasonable, just and unbiased. It is now more clear than ever before that we should devote significant attention to developing and creating resources to make government procurement officers savvier customers of increasingly complex technical tools. Many avenues for revising or improving algorithmic tools, as well as their rollout trajectory, are defined by procurement agreements signed before implementation begins. The role of procurement as pivotal in shaping government use of algorithmic tools was highlighted throughout the year as we engaged with government officials, including state attorneys general (through our spring 2018 AGTech forum on AI),⁴ state legislators in Massachusetts (through our advocacy around the Massachusetts criminal justice reform bill, early versions of which incorporated calls for adoption of risk scoring technologies during the pre-trial phases of criminal adjudication),⁵ and judges. The Media Lab’s HAL team has also contributed to this effort through its’ team members engagement with administrators in state-level pretrial service agencies on the one hand, and organizations involved in the bail reform movement on the other.

- We decided early on to address the need for data on existing tools (and regulation and adjudication of disputes regarding those tools) by developing a risk assessment tool database, collecting publicly-available information on tool use, design, and caselaw and related interventions addressing the implementation of such tools.⁶ As we collected information for the database and read about and spoke to participants in government programs that incorporate algorithms in their decisionmaking, it became clear that some key causes for concern stem from poorly-defined programmatic goals, hazy visions of success, and vague approaches to measurement and evaluation. Part of the reason procurement plays such a pivotal role in ethically implementing algorithmic tools is the opportunity it presents for: (a) laying out a comprehensive adoption framework with clear goals; and (b) deciding upon means of rigorous study and evaluation. In their paper “Interventions over Predictions: Reframing the Ethical Debate for Actuarial Risk Assessment,” the HAL team, along with Joichi Ito and Jonathan Zittrain, connected this pragmatic realization with an ethical one, reframing the debate about risk assessment tools as “not simply one of bias or accuracy. Rather, it’s one of purpose.”⁷ We see a clear opportunity to help governments better map out their policy aims in their turn to algorithmic tools (and whether they match the capabilities of said tools); to educate them on the need to regularly and empirically evaluate such programs; and to point them toward tools and resources to aid in such evaluation.

- There is an immense appetite in the research community for: (a) access to tools; and (b) access to data sets on which to test new and existing tools. Both of these raise complexities, but each merits significant attention. Our risk assessment tool database will provide important information about available tools to direct a variety of further inquiries from researchers and activists alike; however, in most cases it will not offer access to the tools themselves. Opacity around the technological underpinnings of risk assessment algorithms (and other algorithmic decision-making tools) continues to present roadblocks to research — roadblocks we hope may be addressed as public engagement with these issues incentivizes companies and governments toward transparency. Regarding data sets, in particular, we and our colleagues on the HAL team have begun a dialogue around what it might mean to create robust data sets for use in pursuit of scholarship and the public interest. These efforts began with a multi-stakeholder meeting at the Media Lab in March 2018 and will continue as we look to develop coalitions to collect such data.

- We began this process with an inkling that there might be conflicts between: (a) the need for explainable algorithmic decisions to satisfy both legal and ethical imperatives (on the one hand); and (b) the fact that AI systems may not be able to provide human-interpretable reasons for their decisions given their complexity and ability to account for thousands of factors (on the other hand). We continue to have those concerns. A working group of computer scientists, lawyers, and social scientists collaborated this past year to elucidate these competing factors and suggest a way forward in “Accountability of AI Under the Law: The Role of Explanation,” with Finale Doshi-Velez of the Harvard University John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and Mason Kortz of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society as lead authors.⁸ We anticipate significant further work in this field.

- Entering this year of inquiry, we noted that many stories about government use of algorithms tended toward the hyperbolic. Their use was disastrous or inspired, and their spread an inevitable tragedy or cause for celebration. To an extent, the ability to influence this trend in the name of justice or fairness was also viewed in the language of extremes: government actors were not knowledgeable about AI and likely not to understand its broader implications in time to make thoughtful policy. We aimed to bring nuance and pragmatism to the conversation over the past year by highlighting research that contextualized specific government uses of algorithmic tools and making a concerted effort to engage decisionmakers from this perspective. At our May AGTech Forum, state attorneys general and their staff participated in hypothetical exercises around AI applications and discussions with experts to think about how they might change their work to anticipate the challenges these technologies bring. We also made proactive appeals to the Massachusetts state legislature to provide context and recommendations during the criminal justice reform process, in two letters co-authored between Media Lab and Berkman Klein Center experts. These appeals emphasized a measured and research driven-approach to the decision to adopt a risk assessment tool for pretrial rather than full-scale adoption. In these and other moments, it became clear that, given an opportunity to learn, those who develop policies and enforce laws understand the inherent issues around government use of algorithms and can become savvy and interested parties at the table.

- Our initial approach and methodology focused attention on US legal frameworks and constitutional considerations like equal protection and due process that arise in the context of tools that are opacity and susceptible to bias. But, we quickly realized that a more global approach — including comparison with other national approaches and consideration of transnational legal and governance regimes — is vital to full consideration of these issues. To that end, the Berkman Klein Center has undertaken two separate initiatives. First, the Center has joined as an Associate Partner the SIENNA project, coordinated by the University of Twente (Netherlands) with Trilateral Research (United Kingdom) serving as deputy coordinator. The project has 11 partners and 2 associate partners from Europe, Asia, Africa and America, seeking to — among other things — map the global legal and regulatory environment for a wide range of AI and robotic technologies. he project aims to address ethical issues in the emerging technology areas of human genomics, human enhancement and human-machine interaction and has received funding under the European Union’s H2020 research and innovation programme. We expect to complete a US legal mapping exercise later this year. In addition, the Center has collaborated with the Government of Canada’s Digital Inclusion Lab to address broader human rights implications of artificial intelligence and related technologies. The objective of this ongoing project is to evaluate the impact of AI technologies within the context of the Uniform Declaration of Human Rights. We are developing a set of materials that: (a) highlight the risks that AI may pose to human rights; (b) identifies best practices for identifying, mitigating, and remedying those risks; and (c) recognizes opportunities for such technologies to improve human rights outcomes.⁹

- Along with this more global approach comes a recognition that, while discrete consideration of government activities is meaningful, that cannot happen in a manner entirely divorced from broader consideration of issues relating to fairness and social justice. Governments use black-box algorithmic tools and, simultaneously, regulate the development and deployment of such tools in the private sector. Both sets of actions impact fundamental rights of individuals, and some cross-pollination between the study and evaluation of government activities and government approaches to private activities can lead to better outcomes for all.¹⁰

IV. Looking Ahead

Mindful of lessons learned during our first year of work, we look ahead with some of the following priorities in mind:

- There is a clear sense among researchers in this space that significantly more data are required in order to more adequately and accurately assess the efficacy of existing tools and test new ones. Much of these data relevant to algorithmic tools deployed in the criminal justice system is within the domain of states and local governments. Some such data are routinely collected but difficult to access. Other data may not exist in usable form in the first place. With our Media Lab colleagues, we aim to pursue three avenues regarding increased access to data: (a) continuing to forge connections with government actors to broker data sharing arrangements; (b) identifying existing datasets in the hands of private parties (companies and researchers), and developing mechanisms for enhanced data sharing; and (c) considering whether on-the-ground, observational data collection efforts — e.g., efforts undertaken in collaboration with criminal defense attorneys, regarding courts’ pre-trial and bail practices — might play a role.

- Related to the above, we intend to incentivize increased clarity around legal questions (including privacy issues) implicated by data sharingto ensure that we balance responding to a critical need for data with legitimate privacy, security, and related concerns of those whose data is used to train algorithms. These privacy considerations are especially acute as we seek to pursue some of the aforementioned alternative approaches — designing new uses of algorithmic technologies that operate outside well-defined regimes and processes (and may require data from different fields and jurisdictions).

- From the earliest stage of the initiative, stakeholders interested in developing regimes and protocols to govern tool development and adoption have spoken in the language of standards and standard-setting. This may be conceived as a two-step process: (1) establish technical standards for algorithms that incorporate considerations of transparency, mitigation of bias, and explainability and interpretability; then (2) advocate for procurement guidelines in government that prohibit procurement of applications that fail to meet those technical standards. There is a third, intermediate step between these two, which involves auditing and certification of standards compliance. A number of legal, regulatory, and intra-industry regimes exist to do this sort of thing in a wide variety of sectors, including privacy, security, and health-and-safety. But, this may be a particularly difficult task when it comes to AI, algorithms, and machine learning, due both to technical complexity and opacity. It is vital that we probe available models for this step that ensure compliance and properly align incentives.

- We seek to expand and deepen our government engagement efforts, continuing our involvement with the state attorneys general community through our AGTech Forum programming and expanding our educational role with judges (in Massachusetts and beyond). With our greater understanding of the importance of procurement decisions in this environment, we will develop new modes of engagement for government procurement officers to improve their capacity as discerning customers for algorithmic technologies. This effort will include refinement procurement best practices and development of educational materials and programming to serve these communities.

- In the first year of the Algorithms and Justice work, we sought to holistically understand the environment for development, procurement, and implementation of algorithmic tools as it currently exists. As we look to the next year and our efforts to educate government about making algorithmic decisionmaking more transparent, fair, and equitable, we hope to also engage the many groups that develop algorithmic tools for government. We hope to bring them to the table to discuss their work and ours and ways in which they might help better the ecosystem for all players involved.

- Finally, we have long described criminal justice as a case study of government use of technology. We have focused on risk assessment in the context of bail, sentencing and parole, but we have always planned to take lessons learned in the context of risk assessment and apply them to a broader range of technical interventions in government. This coming year, we hope to carry through and consider the role of algorithmic technologies in connection with issues such as those raised by use of algorithms in assessing Medicaid benefits to evaluating teacher performance.

Conclusion

We look ahead toward the second year with a few slight modifications to our underlying mission statement, recognizing the unique value of a focus on government action while acknowledging that considerations that impact government use of these tools are inextricably intertwined with a larger movement toward just and fair models of development and deployment:

The Algorithms and Justice project: (a) explores ways in which government institutions incorporate artificial intelligence, algorithms, and machine learning technologies into their decisionmaking; and (b) in collaboration with our colleagues working on Global Governance issues, examines ways in which development and deployment of these technologies by both public and private actors impacts the rights of individuals and efforts to achieve social justice. Our aim is to help companies that create such tools, state actors that procure and deploy them, and citizens they impact to understand how those tools work. We seek to ensure that algorithmic applications are developed and used with an eye toward improving fairness and efficacy without sacrificing values of accountability and transparency.

We are thrilled with the significant attention being paid to the use of AI, algorithms, and machine learning technologies in government and to the larger social justice issues implicated by the use and development of those tools. We are pleased to be one node in a large network of individuals and organizations thinking critically about these issues, and we encourage feedback, welcome collaboration, and look forward to refining our approach over the coming year.

¹ Much of the action to date with respect to use of algorithmic tools in government takes place at the state and local level, though this same basic rubric might be applied at the federal level.

² Jonathan Zittrain highlighted some issues around the nature of human interaction with autonomous systems in a piece last year that teed up a number of the issues that have been at the heart of our work. See Jonathan Zittrain, “Some starting questions around pervasive autonomous systems,” Medium (May 15, 2017), available at https://medium.com/berkman-klein-center/some-starting-questions-around-pervasive-autonomous-systems-277b32aaa015.

³ Development of technical approaches to testing — and even building of new tools and comparing outcomes among them (or across new and existing applications) — are vital parts of this process. Some of these functions are being handled by collaborators and colleagues in the broader Berkman Klein Center orbit.

⁴ The Berkman Klein Center held two convenings during the past year under the banner of its newly-constituted AGTech Forum program. The second of these — held in spring 2018 — addressed the ways in which state attorneys general are addressing the use of AI and related technologies in their enforcement activities. The scope of this convening — which included state Attorneys General, Assistant Attorneys General, and others from around the United States — encompassed both public and private sector applications. We hope it will serve as just the first step in longer-term engagement with state attorneys on issues that range from consumer protection to health-and-safety to criminal justice. See Kira Hessekiel, Eliot Kim, James Tierney, Jonathan Yang, and Christopher T. Bavitz, “AGTech Forum Briefing Book: State Attorneys General and Artificial Intelligence” (May 8, 2018), available at https://cyber.harvard.edu/publications/2018/05/AGTech.

⁵ Spearheaded by members of the BKC and MIT Media Lab teams, a number of MIT- and Harvard-affiliated researchers joined open letters sent in fall 2017and spring 2018 to Massachusetts legislators considering statewide criminal justice reform legislation. Early versions of what ultimately came a bill passed in Massachusetts in spring 2018 called for adoption of risk assessment tools during pre-trial (bail) stages of criminal adjudication; the final legislation, as passed, called for creation of a commission to study the issue for a year.

⁶ We expect to launch the database later this year.

⁷ Chelsea Barabas, Karthik Dinakar, Joichi Ito. Madars Virza, Jonathan Zittrain, “Interventions over Predictions: Reframing the Ethical Debate for Actuarial Risk Assessment” (2018), available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.08238.

⁸ Finale Doshi-Velez, Mason Kortz, Ryan Budish, Chris Bavitz, Sam Gershman, David O’Brien, Stuart Schieber, James Waldo, David Weinberger, Alexandra Wood, “Accountability of AI Under the Law: The Role of Explanation (last revised November 21, 2017), available at https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.01134.

⁹ These materials include a set of online visualizations — ”Artificial Intelligence and Human Rights” — developed with support from the Digital Inclusion Lab, Global Affairs Canada, available at http://ai-hr.cyber.harvard.edu/.

¹⁰ This theme resonates with themes emerging in other areas of study concerning online conduct and discourse, as we recognize and reckon with the extraordinary power and impact of private actors. In some arenas, such power may eclipse the power of government. For example, speech regulation by the state may raise concerns about civil liberties and the right to free expression not technically implicated by private actors’ moderation practices. But, both have extraordinary impacts on real people. Lessons learned in the context of speech regulation by courts and legislatures (including the large body of First Amendment law that sets the bounds around the government’s very limited right to restrain speech) may not directly apply to private actors setting policies to address online harassment, extremism, and the like. But, frameworks (particularly around transparency and process) may have resonance in both arenas. The same is true as we evaluate public and private actors’ deployment of the types of technologies that are subjects of our Initiative — algorithms used to assess risk at the time a court makes a bail decision, algorithms used by a self-driving car as it seeks to balance safety and efficiency in its driving decisions, and algorithms used by online platforms in delivering content to users raise concerns that are both unique and discrete (on the one hand) and tightly linked (on the other hand). None of these may be considered in a vacuum.

The development, application, and capabilities of AI-based systems are evolving rapidly, leaving largely unanswered a broad range of important short- and long-term questions related to the social impact, governance, and ethical implementations of these technologies and practices. Over the past year, the Berkman Klein Center and the MIT Media Lab, as anchor institutions of the Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Fund, have initiated projects in areas such as social and criminal justice, media and information quality, and global governance and inclusion, in order to provide guidance to decision-makers in the private and public sectors, and to engage in impact-oriented pilot projects to bolster the use of AI for the public good, while also building an institutional knowledge base on the ethics and governance of AI, fostering human capacity, and strengthening interfaces with industry and policy-makers. Over this initial year, we have learned a lot about the challenges and opportunities for impact. This snapshot provides a brief look at some of those lessons and how they inform our work going forward.

You might also like

- storyAI as commons