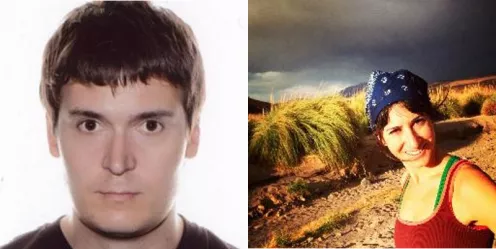

Welcome New Fellows: Dariusz Jemielniak and Rebecca Richman Cohen

By Summer 2015 Interns Sandra Rubinchik and Muira McCammon

Q&A with Dariusz Jemielniak

http://www.jemielniak.org/

@JemielniakD

Dariusz Jemielniak is a professor of management at Kozminski University in Warsaw. He heads the Center for Research on Organizations and Workplaces (CROW) and founded the New Research on Digital Societies (NeRDS) group at Kozminski. Jemielniak’s interests include open collaboration communities, so it’s no surprise that he is an active participant in, as well as critic of, the Wikimedia movement. Jemielniak is currently working on a study about the professional identity of LL.M. graduates, and he also created and runs ling.pl, the largest and most popular Polish online dictionary.

This interview was conducted by Berkman summer intern Sandra Rubinchik. When Sandra wasn’t working on the Privacy Tools project, she was researching Cambridge coffee shops and subsequently funding the ones with the best oatmeal chocolate chunk cookies.

What are some of the environmental and other factors that are necessary for an open collaboration community to thrive? Are there certain projects that are not well suited for open collaboration?

First of all, the minimal contribution that is required to participate must be really small - that is, escalation of commitment must progress gradually. Also, there cannot be too much collaboration in "collaboration" required - all cross-dependencies increase the risk of failure. Additionally, we know from experience that people prefer projects that do not rely on external credentials and allow people to take the role of experts in different fields.

In your studies, what is the most interesting or unexpected thing you have learned about the Wikipedia community?

I was actually surprised by the level of conflict and aggression present on Wikipedia - even though I have to proudly admit that we, Wikipedians, are taking large steps to change that!

What are some of the differences between the Polish and the U.S. Wikipedia communities?

Polish Wikipedia is a much smaller community, practically all admins know each other, at least virtually. As a result, there is much less careless and uncontrolled actions from them, which is good, as any hostility or injustice, especially towards newcomers, is detrimental to user acquisition. Also, the Polish Wikipedia community appears to be a bit more flexible about rules, when needed, yet both suffer from extreme bureaucratization (which is surprising for a movement so ostensibly anti-establishment and anti-structural).

Could you give us a little glimpse into your study on LL.M. students and the professional identity of a lawyer?

My findings show that LL.M. lawyers, quite universally, suffer from the same time pressures and deskilling practices of large corporations all over the world. Time, rather than quality of work, often becomes the more important performance indicator. Interestingly, lawyers share strong commitment to their clients, and even if they unanimously complain on the conditions of work they have to face, they are highly dedicated (which is characteristic of many other professions).

What sparked your interest in creating an extensive online Polish dictionary?

It was the most natural impulse in the world - I needed one! At the time there was no good online dictionary, especially aggregating results from many different dictionaries all together. So I started one and currently it is by far the largest database of this sort in Poland.

And this might be the hardest question, so apologies in advance — what is your favorite word in any language, and what does it mean?

Haha, a tough one indeed! I like the word "pundit", as it has nice origins and I use it as a jocular nick on Wikipedia. I also like "denouement", as even when people know how to spell it correctly, they often mispronounce it. It is also a good word to check dictionaries for - many will not contain it. But I'll have to go with "jejune shenanigans" as my favorite phrase in English, not just because I enjoy the way it sounds, but also because I enjoy what it denotes.

***

Q&A with Rebecca Richman Cohen

http://racinghorsepro.com/

@rebeccaracing

Rebecca Richman Cohen has been a Lecturer on Law at Harvard Law School since 2011. She is an Emmy Award nominated documentary filmmaker and graduated from Harvard Law School and was a 2012-2013 Soros Justice Fellow. Her first documentary War Don Don (2010) examines the trial of Issa Sesay, a former Sierra Leone rebel leader, at the Special Court of Sierra Leone; her second film, Code of the West (2012), looks at the many stakeholders involved in Montana’s marijuana policy reform. She will be a Berkman Fellow for the 2015-2016 academic year.

Muira McCammon is a current M.A. candidate in Translation Studies at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, where she explores the interplay between language barriers, law, and libraries. Her most recent work has been published in The Kenyon Review Online and Words without Borders. Muira’s current research focuses on the U.S. military-run libraries at Guantánamo Bay. This summer, she interned with Internet Monitor!

Before filming War Don Don, you spent a summer working on the Defense Team at the Special Court for Sierra Leone and earlier, in 2005, you made a short documentary titled Nuremberg Remembered. Were you - based on your background - ever tempted to just do documentaries on exceptional courts and military commissions exclusively? There seem to be so many war and military tribunals whose stories haven't been told in full yet.

No. I was not even a little tempted. When you're doing long form storytelling, it's a very immersive experience; it tends to consume you for a number of years. One of the things I like about being a documentary filmmaker is that in a meaningful way, I get to be a generalist; I get to learn a lot about a lot of different things. Generally, I think I'm most interested in things related to the world of criminal justice and reform but very disparate parts of that reform movement. I'm usually very excited to try something new when a project's finished.

So then, how do you go about deciding which documentaries you want to pursue?

I'm interested in the same things that took me to law school in the first place, which is how do you make the world a better place even on a small scale, even in ways that are difficult to quantify, like changing opinions or challenging assumptions. And law is one vehicle to do that, even though it may be a very limited vehicle . So, knowing how to interface with the media is an incredibly powerful tool and one that is gaining momentum as a new element in law school curricula. But to get back to your question, all of my films have been driven by the desire to show in a visual way, in an emotional way, the experience of being impacted by our laws and policies. For me, I have been drawn to explore a range of issues, from international criminal justice to direct marijuana policy reform. Right now I'm working on a film about sex offender laws.

To go back to an earlier comment you made about films being vehicles, it's interesting to track how both of your documentaries have had different afterlives. Wasn't part of your documentary, Code of the West, ultimately used in court? Could you talk about that experience and explain what happened?

In documentary filmmaking communities, calling something an “advocacy film” can be sort of derogatory. It can signal that you're privileging advocacy over craft. Many very well-crafted films also have advocacy campaigns that go along with them, but a commitment to storytelling and craft first. I don't think we set out with clear intentions to make Code of the West as an advocacy film but sixth months into filming, the story took a sharp turn. The marijuana farmers we had filmed for more than six months were raided by the federal government – and we knew that we had a responsibility to reveal the profound injustice of it all.

The film was used as evidence in the sentencing phase of Tom Daubert's case. And there was a very flattering article that was headlined: "Did Rebecca Richman Cohen's Medical Marijuana Documentary Save a Man from Prison?" Nonetheless, I think that's actually a very misguided title, because the answer is no, my film didn’t “save” Tom Daubert. But we were able to convincingly demonstrate to the federal judge that these guys were giving tours of the grow house to state law enforcement officials and legislators, secure in the knowledge that they were in compliance with state law.

An even more powerful use of the film was the seven minute New York Times op-doc that I produced about Chris Williams' case (he's also featured in the film). In a short time it attracted hundreds of thousands of views and Congressmen as well as celebrities were tweeting it. It seemed to have a constructive effect that was hard to measure. But I think the most tangible responses to the film was not reflective of the hundreds of thousands of people who saw it on The New York Times' website, but rather the commentary of The New York Times editorial board, which last summer voted unanimously to support ending federal marijuana prohibition, citing Chris Williams' story as one of the things that swung the editorial board’s opinion.

Impact is a big question with documentary filmmaking. How do we measure the impact of a film? It's a question that filmmakers often resist and resent, because it's very hard to measure certain things that films do well. It's hard to measure engagement and empathy, creating understanding and awareness. These are important qualities that films capture that shouldn't necessarily be reduced to a numerical value.

It may be difficult if not impossible to gage how the film influenced hundreds of thousands of people. Yet it has become clear that the film was influencing a very select number of people, who were in positions of power. I think filmmakers need to think creatively, both about how to engage very broad audiences but also very narrow, specific audiences.

That ties back to the work that I'm doing at the law school, which is teaching how to use video as a tool for advocacy. It's an important to think about how to engage a mass audience, but it's also a very important to think about how to engage a specific audience, like judges or juries or policymakers. The later calls for a very different, but related skillset than then that required for making films for mass audiences.

How has your perspective on the importance of documentary filmmaking changed?

That's a great question. I think my perspective on this field is always changing. I teach a seminar and a reading group that are both related to media literacy, helping law students watch film and media in a sophisticated way. And often on the first day of class, one of the things I'll do is encourage students to eschew the use of the word "objective." That's a word that really irks me. It seems to be a default that lots of people invoke instead of saying, "That was a very fair portrayal or a truthful rendering." They'll say, "That was such an objective portrayal." I have come to the conclusion that framing a response in this manner reflects a profound misunderstanding of the way that media is produced as well as consumed. It fundamentally ignores the ways in which we bring our perspectives and experiences to bear on creating and consuming representations of the world.

So, I often start class with a screening of the Rodney King beating and ask students what they see. Across the board, students say, "Oh, the police officers were using excessive force. That was incredibly brutal." Then you see how a very talented group of defense lawyers represented it to a largely white jury in suburban Los Angeles, and how that jury saw something very different.

The way we understand the context around the images that we consume really changes the meaning of those images. They are not locked in a specific meaning. And so, one of the purposes of the class is to bring context into sharp relief. I see the importance of doing so when my students react to all these horrific videos documenting police violence that have emerged in the last two years. It's hard. Students have really pushed and initially said: "Well, look at the Walter Scott shooting; that looks like objective evidence. You don't have to be a black person. You don't have to have a specific context to understand." But subsequently, they come to appreciate how the meaning of the evidence can be manipulated by creative rendering. For this reason, I think this generation of students is more media literate than previous generations of students.

Does that give you hope?

Yes. I mean, the question is: how do you translate media literacy into activism, into a sustained social movement? I'm hopeful that these videos will be a catalyst for more than fleeting engagement, that it will produce meaningful change, that they will engender outrage in Americans who are not exposed first hand to the brutalities that people of color experience with such frequency. I think that is something important to explore and unpack in a classroom setting, and I think that's directly related to the work of lawyering for social justice.

I want to return to the metaphor that documentary films are vehicles. There's a clearer paper trail for what happened to Code of the West. It's harder for me to tell what happened in Sierra Leone after War Don Don came out. What type of outreach did you all do, and where did War Don Don travel?

We dubbed the film in Krio and then also traveled around doing public screenings of the film in communities across the country. The Court worked with our team and provided an outreach officer, who came to answer questions about the Court. In the end, they were very supportive, even though it was a film that raised some criticisms of their work. I think we both wanted the same thing: to have a dialogue about the Court and its efforts, about how you measure its success. Most of the major tribunals held screenings with judges and lawyers. The FBI War Crimes Investigation Unit hosted a screening. The CIA and State Department did as well. We did a screening in Congress. So, policymakers and people in positions of power saw the film. But still, it's not a film that advocates for an unambiguous outcome. It's not a film that says, "Let's get the bad guy."

There seems to be a lot of uncertainty at the end of War Don Don.

Right. It's an open-ended film, but what we set out to do was to show the inner workings of the Court in a way that's very hard to see from the outside, to provoke a critical discussion about its purposes. So much of the pursuit of international criminal justice seems to be dependent on the willingness of states to support it, while the domestic politics of these states may not be aligned with criminal justice goals. As a result, the domain of international criminal justice has needed a lot of cheerleaders. This need to muster support for these tribunals has dampened the enthusiasm of its advocates to enter into a critical debate about its purposes and effects.

The other thing we were trying to do was portray a man, who was accused and ultimately found guilty of egregious crimes, as a human being, because there is a narrative that pervades the international criminal justice movement which argues that the commission of such crimes is the responsibility of a few bad apples. There's the idea that if we take out these very powerful, terrible people, like Kony in 2012, the world would be a much better place. And yet, while removing people from power who have abused their authority can be a good thing, that alone may not be sufficient to restore justice.

I think there's lots of powerful reasons why the pursuit of international criminal justice is of the utmost importance, but I think that pushing the narrative of a few bad actors obscures the root causes of these conflicts and makes it harder to confront them. The international criminal justice movement does a disservice to itself, when it paints perpetrators of war crimes as - in the words of David Crane, the Chief Prosecutor of the Special Court for Sierra Leone - as people who have "no soul." If you can see perpetrators of mass atrocity not as people who have no souls and are not human, but if you can see them instead as very human, then I am persuaded a very profound transformation is at play. That would be a measure of success for transitional justice mechanisms to appreciate the nuances and complexities of these situations and to hold in our minds the cognitive dissonance of seeing people both as victims and perpetrators without having to paint them in such stark black and white colors.

So, what are your goals as your year as a Berkman Fellow? It sounds like you have a lot on your plate for this upcoming year.

My intention for this year is to think through how to deepen and expand the work of familiarizing aspiring social justice lawyers with the uses of media as a tool for advocacy. I say deepen, because it's work that's already been going on in a meaningful way at the Harvard Law School; a number of clinics have launched media advocacy projects. I had the privilege of working with the Human Rights Clinic two years ago, and we produced a short video that was employed in human rights litigation in South Africa. Students affiliated with the Food, Law, and Policy Clinic and I are about to finish a short video about food expiration dates in support of federal legislation they're proposing. These have been incredible experiences, which have afforded the students opportunities to do hands on work—strategizing, messaging and figuring out how to use visual language, how to use video as a tool to support their campaigns.

One of the questions that I'm excited to think through in a community of people who do similar work, who use media and the Internet as resources to seek social justice, is how to bring these initiatives to scale, which concretely translates into how to engage a much larger number of students.