Country Spotlight: Singapore’s TraceTogether Program

Student contribution

The following was written by Melyssa Eigen, J.D. Candidate at Harvard Law School, under the guidance of Professor Urs Gasser. This is the third installment in a series of briefing documents about COVID-19 apps in several countries around the world. Previous briefing documents cover Switzerland and Germany.

An Overview

On March 20, 2020, Singapore’s Ministry of Health (MOH) and Government Technology Agency (GovTech) launched TraceTogehter, the world’s first nationwide contact tracing app. Recently, Singapore also released a wearable token as part of TraceTogether for those who do not have mobile devices, notably seniors, which began distribution on June 28, 2020. While slightly different in technology, the token is interoperable with the app and also functions to supplement the ongoing contact tracing effort. The following describes the program’s technological, data, institutional and behavioral aspects as well as some other key points about TraceTogether.

Technological:

The TraceTogether app is a Bluetooth-enabled contact tracing app. Like many of the apps being used elsewhere, it detects other phones in their vicinity, exchanges encrypted IDs, and records encounters. What’s different, however, is that if a user becomes infected with COVID-19, the MOH will request that the user upload the data from their app to a central server, so that it’s accessible to MOH. MOH will then contact other users who were in contact with the infected user, based on the app’s contact log, and will provide them with additional instructions. TraceTogether was built before Apple and Google developed their decentralized DP-3T model, and uses the BlueTrace Protocol instead. The app had compatibility issues with iOS and battery life issues early on, but recent updates that allow the app to run in the background have helped.

The early compatibility issues and a desire for accessibility led Singapore’s government to introduce the TraceTogether token. The token uses the same BlueTrace Protocol to collect encrypted IDs of contacts for encounters within 2 meters for 30 minutes or more. The tokens, which are designed to be worn on a lanyard or placed in a pocket, not only work with other tokens but also with the app itself. They do not have GPS, internet or cellular connection, and have a battery life of up to 9 months. If a user becomes infected, the MOH will ask them to turn in their token, so that the MOH can perform contact tracing.

Data:

Like other apps, neither the TraceTogether app nor the token collect location data, just the Bluetooth proximity data that is stored locally on the devices using encrypted IDs. Beyond this, the app only stores the user’s phone number, while the token stores no additional information at all. Each token has a unique QR code, designed to be used by the specific recipient only. Only the MOH has access to a private decryption key that allows them to read the contact data that is provided by infected users. For the app, the MOH only can decrypt the data once it is uploaded by the user. For the token, data cannot be accessed remotely and users must physically turn in their token in order to extract the data. The encrypted contacts are automatically deleted after 25 days. While the encrypted data is generally deemed secure, its reversible nature has caused criticism due to the possibility of the MOH’s decryption key becoming compromised.

Institutional:

The TraceTogether program was developed by the MOH and GovTech in a cohesive response effort to COVID-19. Further, the task of distributing the tokens and providing instructions has been given to volunteers from Singapore’s Silver Generation Office. Singapore’s long standing Infectious Disease Act (IDA) largely confers power to the MOH to manage a pandemic, allowing them to issue ‘Stay at Home Notices’, monitor those who are infected and penalize those who violate restrictions. The IDA specifies the data which can be collected by the MOH, giving a legal basis for the data collected by TraceTogether. Singapore’s 2018 Public Sector Governance Act in combination with their Public Sector Data Review Committee provide protections against data misuse and provide data security measures that the government must comply with. Singapore also has a Personal Data Protection Act, but this does not apply to data collected for and used by public agencies.

The TraceTogether app is voluntary, except for migrant workers who must download the app to be eligible to work in Singapore. For these workers, the TraceTogether app is integrated into another app, SGWorkPass, which lets the workers know each day whether or not they are approved to leave their residence for work. There is an ongoing debate over whether to make the app mandatory for everyone, not just for migrant workers. Currently, the token is also voluntary, and there is similar debate over whether it will become mandatory. The token has mainly been a government endeavor, but the bid for production was awarded to PCI, a Singapore-based technology company. Beyond this, the government invited a small group of hackers to examine the tokens in what was called a ‘Tear Down’.

Behavioral:

Since the app’s release in late March, an estimated 35% of Singapore’s population have downloaded it. While helpful, the government did not believe the app was effective enough, leading them to develop the token. The token has created a privacy backlash in Singapore, a place where people usually respect and do not question the government, leading some to sign a petition against the token. Phrases like “surveillance state” have been thrown out by those concerned, fearing for compulsory use and the government scaling the token’s infrastructure to track its citizen’s movements. Despite this, participants in the government’s ‘Tear Down’ generally approved of the technology, finding it to be secure. Beyond potential privacy concerns, one participant discussed the difficulty in rolling out bug fixes as a downside to the token. Still, the reactions from the first batch of token recipients have been generally positive -- one stated that even though he didn’t know how it worked, he felt more assured. Another said that carrying it around has been convenient.

What makes TraceTogether interesting?

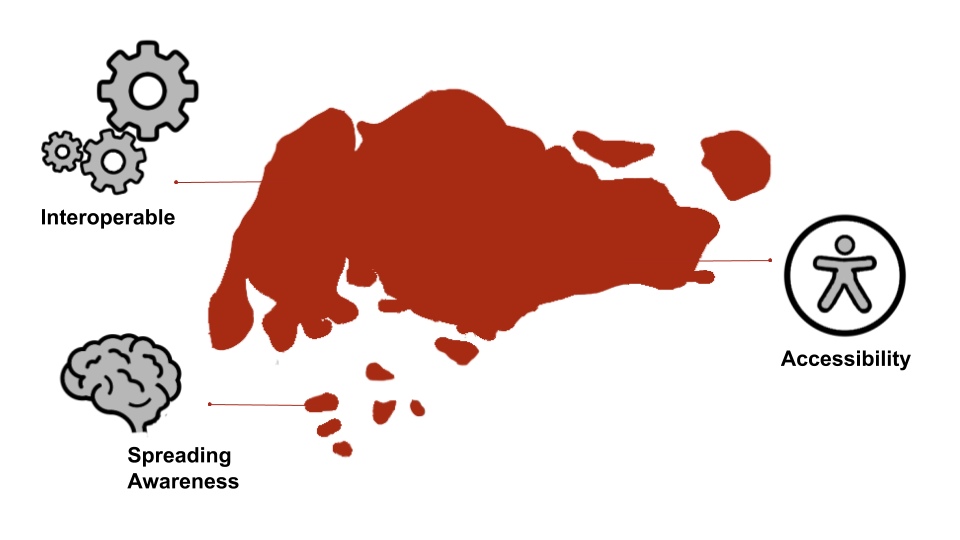

Interoperable:

TraceTogether is not just an app, but a multi-tool program. While it began with the app alone, GovTech could have decided to amend the BlueTrace Protocol or scrap the app altogether after experiencing battery life problems and compatibility issues with iOS. Instead, Singapore chose to design the tokens to supplement, but not replace, the existing framework. The tokens use the same BlueTrace Protocol and thus work in tandem with the app -- the tokens can detect each other as well as phones with the app. Regardless of whether the user has the app or the token, they are still recording their encounters and aiding in the contact tracing process. If successful, the tokens may serve as a model to other countries. As of July 6, 2020, the TraceTogether app is also integrated with Singapore's SafeEntry, an app where users check in and out when they enter businesses. Users can now scan the SafeEntry QR codes with their TraceTogether app, making the process more efficient. For all businesses currently in operation, SafeEntry is mandatory for “employees, associates, and vendors”, and in many places, is also mandatory for consumers or anyone else visiting the business. Additionally, the TraceTogether app is also integrated with Singapore’s SGWorkPass, an app that allows foreign workers living in Singapore to check their work status -- it tells them whether they are able to leave their residence to go to work, which is based on their health, location, and company’s status. While they each serve their own purpose, TraceTogether, SafeEntry and SGWorkPass all work towards a united response to COVID-19.

Accessibility:

Beyond technological issues, Singapore designed the token to fill in the gap for those people who have not or cannot download the app. The government estimates that 20% of all Singapore residents do not have mobile devices. This “digitally excluded” population includes poor communities, the elderly and young children. As such, these groups are the government’s targets for the token, which will be provided for free, in an effort to increase the effectiveness of contact tracing by making tools more accessible to all groups. Not much has been said about how exactly the government is prioritizing and selecting token recipients. However, the first batch of 10,000 tokens was distributed to the most “vulnerable” amongst these groups, specifically seniors who live on their own without a support system or those who are physically more susceptible.

Spreading Awareness:

Another benefit to Singapore’s approach is the added opportunity for public engagement, and thus, increased awareness about the country’s efforts to mitigate COVID-19. Key to the token’s rollout are volunteers who will personally deliver them to recipients. These volunteers will explain how to use the token and why they are important, and will even leave an instruction infographic with each recipient. Unlike with the app alone, where people can download it without really understanding it, physical delivery of the token makes the public more aware and perhaps more likely to adhere to the government’s recommended practices. Given that there is no open source code available for the token, although the source code for the app has recently become available, the in-person instruction is important towards making recipients feel assured. Further, members of the government plan to engage with seniors over the phone and in other forums to continue spreading awareness.

[1] Thank you to Nydia Remolina and Professor Mark Findlay at the Singapore Management University for their input on this topic.