Textbooks: Difference between revisions

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

However, uncertainty regarding monetizing new free-content models (as seen in the newspaper industry), along with the perception of massive piracy in the music and film industries, has led to traditional publishers seeking ways to deliver textbook material through proprietary digital platforms or sell e-textbooks copyright-protected by digital rights management. What remains unclear is whether the market logic of the major publishers is ideologically incompatible with the open, unregulated commons, and which balance of economic, political, and social factors represents the greatest barrier to such innovation. | However, uncertainty regarding monetizing new free-content models (as seen in the newspaper industry), along with the perception of massive piracy in the music and film industries, has led to traditional publishers seeking ways to deliver textbook material through proprietary digital platforms or sell e-textbooks copyright-protected by digital rights management. What remains unclear is whether the market logic of the major publishers is ideologically incompatible with the open, unregulated commons, and which balance of economic, political, and social factors represents the greatest barrier to such innovation. | ||

=== NEXT STEPS FOR QUADRANTS === | |||

* Vary size of the actors in each area | |||

** For-profit: volume of sales per company | |||

** OER: volume of materials generated, adoption by schools, some kind of weighted index(?) | |||

* Move for-profit and OER projects along axes based on policies and presence of copyleft experimental projects. | |||

* Does Pearson's relative size allow for it to experiment with copyleft more than other for-profit publishers? Is this a new cloud? | |||

* Questions on Data Gathering | |||

** Where can we access lists of mandated materials by publishers? At the state-level? District-level? Can we ask major distributors like Blackwell--contact via Albert N. Greco? | |||

** Is there a way to track individual faculty members (K-12 and HE) that have adopted OER in the classroom? Can we start with a list of contributors to each OER project and extrapolate from there? Can CCCOER give us a list of OER adoptions in its network? | |||

** Can we develop an index that weights volume of OER modules with number of contributors, adopters, and state or college sanctioning of a given OER project's materials? Can this compared to traditional publishers' influence in a post-MakeTextbooksAffordable educational landscape? | |||

= Navigation = | = Navigation = | ||

Revision as of 17:37, 10 August 2009

Introduction

Although our study is not limited to textbooks, particularly when one considers how digital expressions of educational content have begun to blur the definition of a “textbook”, the prominence of this form of EM acts as an important gateway to understand the rest of the EM field. The price of and access to quality textbooks, particularly at the higher education level, has been a recent highly controversial issue. Notably, The Student Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGs) brought the issue to widespread attention with the publication of their report Rip-off 101: How the Current Practices of the Publishing Industry Drive up the Cost of College Textbooks (see #Summary of The Student PIRGs Findings below).

Subsequent government-funded studies and policy movements have created a proliferation of research on the textbook market that unites the ideological questions of access and regulation. Simultaneously, technological affordances have resulted in alternative models of EM production and delivery gaining ground in both the K-12 and higher education levels.

Textbooks in Higher Education

Production and Distribution Cycle

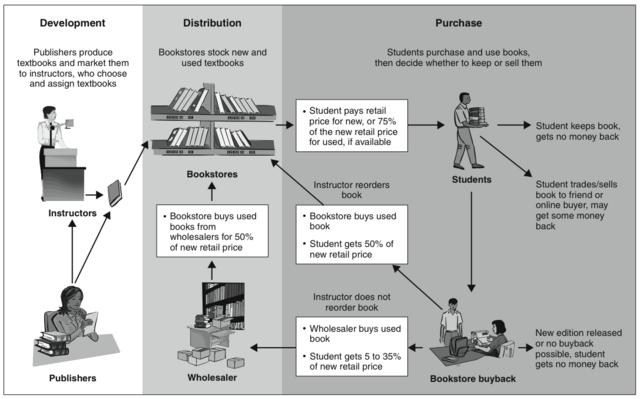

Lisa Shamchuk defines 15 basic steps in the production and distribution cycle of textbooks (Source: Shamchuk 2009, 9):

- Author submits proposal to publisher.

- Publisher conducts a market review.

- A contract is established.

- Editorial team + author develop manuscript.

- Manuscript is reviewed.

- Author approved revisions.

- Cover is designed.

- Supplemental materials is prepared.

- Marketing strategy is developed.

- Index is prepared.

- Book is sent to the printer.

- Book is promoted by sales representative.

- Adoptions are secured.

- Books are shipped to the bookseller.

- Profits are distributed.

The GAO report summarizes the stages in the following picture (GAO 2005, 5):

Summary of The Student PIRGs Findings

The Student Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGs) have brought the issue of access to quality textbooks to widespread attention through their Make Textbooks Affordable campaign, inaugurated in 2004 when they published a research report entitled Rip-off 101: How the Current Practices of the Publishing Industry Drive up the Cost of College Textbooks.

As noted in trade magazines like Publishers Weekly (http://www.publishersweekly.com/article/CA500814.html), the PIRGs study criticizes the industry on the following points:

- Textbook prices are rising "at more than four times the inflation rate for all finished goods" (Rube 2005, 1);

- The most popular texts have new editions published every three years;

- New editions are priced 12% higher than the editions they are replacing, "almost twice the rate of inflation" (Rube 2005, 1);

- Bundled texts are on average 10% more expensive than unbundled counterparts;

- 55% of bundled textbooks are not available unbundled;

- The average textbook costs 20% more in the U.S. than U.K. and some are dramatically more expensive.

Price and Access Issue

Between 1986 and 2004, textbook prices rose 186 percent in the United States, or slightly more than six percent per year. (GAO 2005, 8)

Textbooks in K-12

Quadrants Mapping

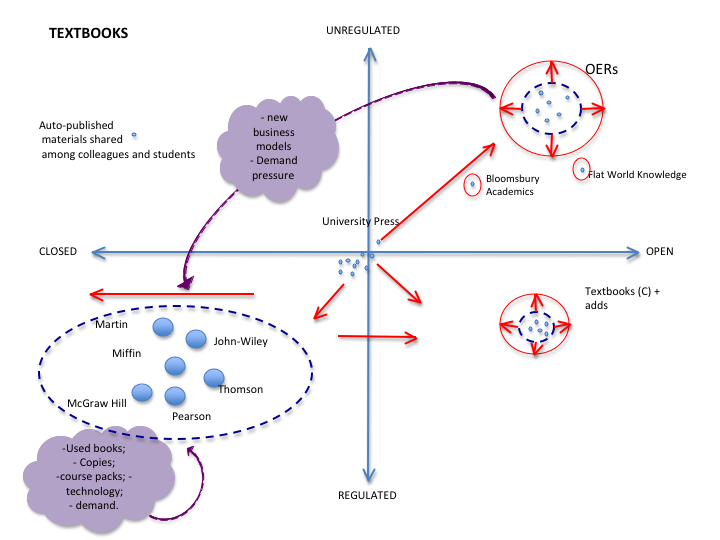

We have plotted our descriptive research of the major actors, market forces, and outputs of the Higher Education textbook market onto our Quadrants tool; our most recent mapping of actors with regard to representative types of commons is shown below. Even with crucial political-economy differences between the textbooks in K-12 and textbooks in Higher education, the final picture of these fields are very similar when regarding the strategies used by incumbents and challengers.

Closed versus Open in the EM Field

The closed versus open axis represents the level of access to participation in the textbook production. The business models of the traditional publishers are vertical in their use of individual authors or small teams of co-authors in producing textbooks. Much of the scholarly works published by university presses are on the closed side of participation as well. On the opposite side of the participation axis, the alternative model of peer-produced and open-source textbooks sponsored by advertising and OER projects allow for open access to the production process. However, some models we could identify on textbooks based on advertisement are “free as in beer,” and not “as in freedom” - representing just a distribution model for e-books, which, in general, have a printed version available for a higher price. This relates to the placement of such models in a different part of the quadrant as they retain more regulations than models where rights are provided to users in addition to no-cost content.

Regulated versus Unregulated in the EM Field

The regulated versus unregulated axis represents the level of regulation of usage embodied by intellectual property tools employed in the licensing of actors’ outputs and also the propensity of the actors enforce their intellectual property rights. OER projects generally use open licensing such as Creative Commons or the GNU Free Documentation License, which has a limited set of regulations regarding the conditions of use of resources â and in most cases enforces different levels of openness. In contrast, traditional publishers and the textbooks sponsored by advertising use copyright in its more traditional sense to severely restricts copying, distribution, and other uses not specifically allowed by the publisher in advance. These incumbent actors also enforces their rights through a series of political, legal and judicial strategies, from which suits against Universities use of course packs are a clear example.

Defining the ‘Clouds’ in EM

The clouds represent actors that do not produce textbooks but affect the sector and can incline actors toward certain types of business strategies, which can be identified either toward closedness or openness. Most fundamental are consumers’ (students’/professors’) demands for quality textbooks from established publishers or for OER. Legislative bodies, as discussed earlier, can affect the market by requiring that constituent schools explore less costly forms of EM that might exemplify models that are less regulated and/or more open to participation. Professional associations can also act as clouds by standardizing intellectual property positions for member actors and advocating for a particular form of EM (like the traditional textbook). Finally, pressure from actors with different business models, such as the ones based on used textbooks, are crucial in understanding changes incumbents adopt in order to keep their dominant position in the market over time. Shorter cycles of textbooks versions and the offer of sale of textbook chapters are a clear example of a reaction.

In the case of the K-12 level, State textbook Adoption Boards are major clouds. The textbook adoption process, in place in at least twenty-one states, is a state-wide process where a central textbook committee or the state department of education review textbooks according to state guidelines and mandate specific textbooks and educational materials that all public schools in a certain state must use, or lists of approved textbooks and educational materials that these schools must choose from. Some of these states allow schools to buy other materials with non-state money. The states that do not hold adoption processes are called ‘Open States’.

Texas, California, and Florida represent the largest markets for textbooks governed by state adoption boards, and publishers try to produce textbooks to specifically gain approval of these boards, which can guarantee access to key public school markets. According to the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, few publishers “can afford to spend millions of dollars developing a textbook series and not have it adopted in these high- volume states.” The persistence of this trend may significantly slow innovation toward other types of commons models because of specific standards in place for these textbooks and the continuing profitability for major publishers touting approved textbooks. This barrier was already identified as a challenge for the recent California open textbooks effort.

Trends in the Field

The effects of the clouds and decisions made by major actors determine the economic, political, and social forces that move textbook production along the axes. Demand for digital delivery of EM has expanded the influence of OER, and led to major publishers and university presses exploring more open access and less regulated business models. This has also created gaps in the market that allow entrepreneursâwith alternative business models like the free textbooks supported by advertising, Bloomsbury Academic, Word Flat Knowledge, and various OER projectsâto gain ground.

However, uncertainty regarding monetizing new free-content models (as seen in the newspaper industry), along with the perception of massive piracy in the music and film industries, has led to traditional publishers seeking ways to deliver textbook material through proprietary digital platforms or sell e-textbooks copyright-protected by digital rights management. What remains unclear is whether the market logic of the major publishers is ideologically incompatible with the open, unregulated commons, and which balance of economic, political, and social factors represents the greatest barrier to such innovation.

NEXT STEPS FOR QUADRANTS

- Vary size of the actors in each area

- For-profit: volume of sales per company

- OER: volume of materials generated, adoption by schools, some kind of weighted index(?)

- Move for-profit and OER projects along axes based on policies and presence of copyleft experimental projects.

- Does Pearson's relative size allow for it to experiment with copyleft more than other for-profit publishers? Is this a new cloud?

- Questions on Data Gathering

- Where can we access lists of mandated materials by publishers? At the state-level? District-level? Can we ask major distributors like Blackwell--contact via Albert N. Greco?

- Is there a way to track individual faculty members (K-12 and HE) that have adopted OER in the classroom? Can we start with a list of contributors to each OER project and extrapolate from there? Can CCCOER give us a list of OER adoptions in its network?

- Can we develop an index that weights volume of OER modules with number of contributors, adopters, and state or college sanctioning of a given OER project's materials? Can this compared to traditional publishers' influence in a post-MakeTextbooksAffordable educational landscape?

Bibliography for Item 3 in EM

Back to Data, narratives and tools produced by the EM field

Back to Data, narratives and tools produced by the EM-K12 field

Back to Educational Materials