Overall Picture of the EM field: Difference between revisions

| Line 128: | Line 128: | ||

=== Higher Education EM Industry Data === | === Higher Education EM Industry Data === | ||

<br> | |||

[[Image:Simba--ShareofMediaUsedinUSCollegeClassrooms--pg14.png]] | |||

<br> | |||

In 2005, Esposito estimates that the college book market is around $7 billion, based on $4.2 billion in net annual revenues to publishers for new textbooks, plus the approximately $1.2 billion used book trade and "all the books that are not formal textbooks that find their way into the curriculum, mostly in the humanities: literary classics, paperbacks on social policy, anthologies, coursepacks (collections of readings), etc." [[Bibliography for Item 2 in EM|(Esposito 2005, 2)]]. | In 2005, Esposito estimates that the college book market is around $7 billion, based on $4.2 billion in net annual revenues to publishers for new textbooks, plus the approximately $1.2 billion used book trade and "all the books that are not formal textbooks that find their way into the curriculum, mostly in the humanities: literary classics, paperbacks on social policy, anthologies, coursepacks (collections of readings), etc." [[Bibliography for Item 2 in EM|(Esposito 2005, 2)]]. | ||

Revision as of 10:39, 22 June 2009

Introduction

Location of Major Publishers

"Since 1639 book publishing has been clustered primarily on the East Coast (mainly in the port cities of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia) and in Chicago. New York City became the center of the industry in the nineteenth century." (Greco 1997, 4) "By 1987 the New York City-Boston-Philadelphia triad no longer dominated the industry. California was the second largest book publishing state, with an impressive 375 corporations. The other principle states were Illinois, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Florida. Pennsylvania was a distinct seventh." (Greco 1997, 5) In the 1990s, "the impact of electronic publishing, the information highway, sophisticated telecommunication systems, computers, and fax machines seem to negate the importance of publishers being located in urban centers" (Greco 1997, 8); "freelance editors, consultants, graphic artists, and others [...] can [now] be contracted out and supervised from some distance because of the availability and usefulness of electronic computer and telecommunications systems."

From Editorial Logic to Market Logic in Higher Ed Publishing

Editorial Logic

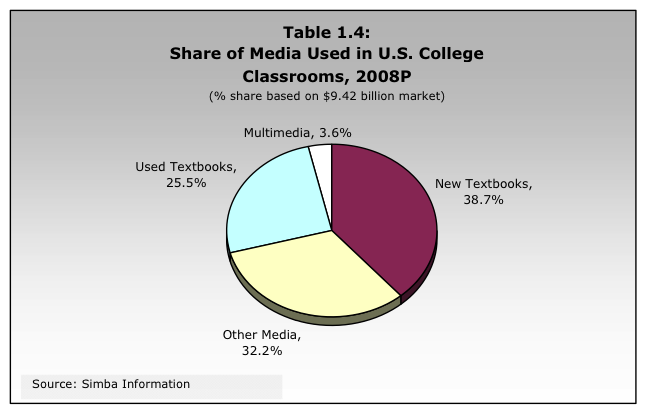

“Publishers described the 1950s and 1960s in higher education publishing as characterized mostly by small houses that were privately owned by families and persons who engaged in publishing as a lifestyle and a profession.” “The dominant form of leadership was the founder-editor, whose legitimacy and authority stemmed from their personal reputation in the field, their position in the organizational hierarchy, their relational networks with authors, and the stature of their books”. “Publishers viewed their mission as building the prestige and the sales of the publishing house." They focused their attention on strategies of organic growth, hiring and developing editors with the best reputations to build personal imprints, develop new titles, refine the backlist of existing titles, and nurture relationships with authors.” ”Capital was committed to the firm for the longer term, and the leader’s life cycle and family estate plans were the salient determinants of executive succession." (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 808)

According one interviewee in Thornton and Ocasio's study, ”most of the companies were small and private" (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 809). Some companies operated as hierarchies: larger companies such as Prentice Hall, McGraw-Hill, and Macmillan. ”Some old-line publishers, such as Wiley and Harcourt Brace, became hierarchies in the 1960s” (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 809). ”When William Jovanovich became president of Harcourt in 1960, he took the company public and began to mold it into a diversified hierarchy”; “at the same time, he continued to run the publishing interests from an editorial logic, centered around a dominant individual with he himself editing manuscripts” (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 810). ”The growth of publishing hierarchies added the attribute of rank in the hierarchy as a salient characteristic of organizational identity under an editorial logic” [[Bibliography for Item 2 in EM|(Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 810)].

Market Logic

"Publishers described a shift that occurred in the organizational identity of higher education publishing sometime during the 1970sâa shift from publishing as a profession to publishing as a business." "The dominant form of leadership became the CEO, whose legitimacy and authority stemmed from the firm’s market position and performance rank, the corporate parent firm, and public shareholders". “The mission was to build the competitive position of the firm and increase profit margins”. "To do so, the focus of executives’ attention changed to counteracting problems of resource competition by using strategies such as acquisition growth and building market channels”. (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 810)

Firms began to actively marketing books, “in sharp contrast to the older editorial logic where it was believed that good books sold themselves by favorable word of mouth” (Powell 1985, 10). ”In the 1960s modern marketing methods were rare in publishing. However, by the early 1980s, most publishers were emphasizing the most advanced marketing techniques” (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 810). "The logic of investment is to commit capital to its highest market return, and the salient rules of succession are shaped by the market for corporate control” (ibid.).

Another of Thornton and Ocasio's interviewees stated: “In the early 1970s, when I was the executive in charge of a division, the company CEO had a serious discussion with me about how I had to get rid of all these little books. Even though my books were important in their fields and selling well, they were in small markets and required the same amount of a sales rep’s timeâtime that could be spent selling a book for a larger market. . . . But my real recognition of how this business had changed came when the parent company asked us not for editorial talent but for management talent for their other divisions. It was the realization that our mission was to grow managers, not book editors” (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 810).

Transition from Editorial to Market Logic

“In the early 1970s, there began a period of transition in logics, which was propelled by”:

- ”new sources of capital in the industry”

- ”an increase in resource competition in the product market after the mid-1970s”

- ”new sources of information from trade presses that emphasized a focus on market logics”

- ”the development of investment banking practices and firms specialized to the industry” (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 811-812).

”In the 1960s, market demand exploded along with the demographic expansion of post-war baby boomers en route to college and with increased state and federal investments in the construction of new colleges and universities”. ”Similarly, the sales of college-level books, approximately $67 million in 1956, had grown to more than $531 million in 1975, indicating that publishers responded to the increased demand in the product market”. "With this growth, Wall Street analysts began to tout higher education publishing as a growth industry, signaling to corporate executives outside the industry, who were engaged in the heralded diversification strategies of this time, that publishing firms were attractive targets for acquisition”. ”Faced with both market growth and increasing competition, publishers needed new sources of capital”. “Family-estate publishers faced two choices: going public to obtain access to public capital markets or securing funding by being acquired”. (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 812)

Parent corporations introduced "new performance expectations for yearly increases in profits and market share". “[This] refocused executives’ logics of investment on market processes and on a new solutionâthe strategy of acquisition growth”. One interviewee responded: ”Every year had to be better than the previous year. The only way to get bigger rapidly is to go outside and acquire others. Then you set up a new kind of industry competitiveness, which is: I want to buy this other company because if I don’t our competitors will get it. So the attention shifts from publishing to what it is we can buy.” Executives told Thornton and Ocasio that "market position and reputation, which had previously taken years to establish under the editorial logic, could be obtained overnight with acquisitions”. Thus, “attention to strategies of acquisition growth and the market for publishing companies created new determinants of executive succession by changing the sources of power and the rules for tenure in the position”. (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 815)

Cementing the new market logic dynamics was signified by ”the founding of the BP Report on the Business of Book Publishing in 1977"; in contrast to Publishers Weekly’s ”features about new books, authors, and imprints, [the BP Report] focused on competitive position, ranking publishers by their control of market share, and providing information on acquisition practices as a means to increase market share” (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 815). "'Acquiring parent,' 'target company,' and 'deal price' were terms used for the first time in the publishing trade literature [â¦]. This 'linguistic framing' of market concepts increased their salience in the minds of publishing executives" (ibid.)

There developed a market for "investment bankers specialized to publishing” (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 815). Accordingly, "deal makers came from Wall Street, and the acquiring firms were located in industries outside of publishing” (ibid.). "Investment bankers now conduct training for publishers in how to “stay ahead of the game” by using acquisitions and consolidation as a business strategy“ (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 816)

"The rise of a market logic in higher education publishing--articulated with observed changes in public ownership, acquisition activity, and resource competitionâallowed publishers to understand these changes and develop suitable responses. The editorial logic--with its emphasis on publishing as a profession rather than a business, its emphasis on author-editor networks, and its emphasis on personal reputation and rank in the hierarchy--could not readily explain or account for the changes in the marketplace nor the rise of acquisition activity after 1975." (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 837)

"The historical contingency of power in organizations and the decline of the professions relative to markets as mechanisms through which power is constituted has significant implications for the development of products such as books and health care that have cultural and political significance. More generally, the transition of institutional logics from professions to markets implies that a different set of values determines the production of products and the distribution of resources in organizations and in society." (Thornton and Ocasio 1999, 838)

Growth of Digital Materials

Although acceptance of e-textbooks is still nascent, "enrollment in online courses is the highest growth segment in higher education, particularly in career-oriented, for-profit institutions. In fall 2006, total higher education enrollment increased 1.3% to 17.6 million with 3.5 million of those students, or 19.8%, taking at least one course online, up 9.7% from 2005, according to the 2007 Sloane Consortium survey" (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 6). "Some states, including colleges in California, are reporting a surge of registrations for online classes, as students forego commuting for the computer" (ibid.). This suggests that their will be significant growth in the future demand for digital delivery of instructional materials.

Simba Information quotes Mark DeFusco, managing director of mergers and acquisition firm Berkery Noyes, discussing Pearson's July 2007 acquisition of eCollege, "As digital content becomes a commodity, publishers are pushing to protect their franchise by acquiring the distribution channel" (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 7-8). In the same report, Macmillan president Brian Napack is quoted, "The market is migrating very steadily online because the customer--meaning the students and professor--demands it" (ibid., 8).

Transition from Traditional to Digital

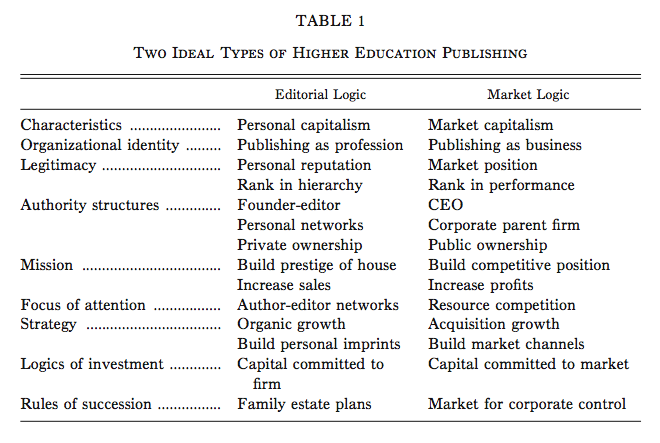

New textbooks still account for "an estimated 39.4% share of the total college materials market in 2007", but this figure is off 0.4% from the previous year with Simba Information forecasting an even greater drop for 2008. Simba argues that this is "troubling as long as the industry remains focused on delivering content in the traditional ways", but "as the digital migration progresses, it may be less of an issue as content becomes available in a variety of means." New textbooks still dominate the market and will likely do so, and the decline can be attributed in part to "the popularity of used textbooks", but "publishers say [...] students simply are not buying textbooks, doing without or sharing a classmate’s". (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 10)

"Publishers have had the most success as they changed from putting a replica of the print textbook into electronic format to moving into the course management sphere with tools that assist instructorsâlike automatic grading and grade-book functionsâand studentsâlike homework assistance and assessments to monitor progress and provide feedback" (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 13).

Main Business Models

In writing any book, the traditional model of solitary authorship plus contractual relationship with a publisher is still dominant. As Albert Greco writes: "Whatever the motive, the stark reality of writing means that the author toils alone, for writing is a singular, hard profession." However, "the author's objective changes. He or she needs a publisher willing to tender a contract to have the novel, biography, or monograph edited, printed, reviewed, publicized, distributed, and, hopefully, read by as many people as possible." (ibidi.)

Commercial publishing firms aim "to sell enough copies to pay the publishing house's employees, taxes, and other expenses while making a contribution to the world of letters. Hopefully, a profit can be made and a royalty paid to the author." (Greco 1997, 1)

As an alternative to strictly commercial firms, University Presses strive "to make a contribution to scholarship while trying to pay the bills" (Greco 1997, 2). (On the need for University Presses to diversify their book lists to survive see Thompson 2005).

Innovation Dynamics in Higher Ed EM

Historically, advances in publishing technology were in the inputs of production leading to outputs such as stone tablets, papyrus, scrolls, and bound books. Burrus (2007, 20) reminds us, generally, that writing solved problems of inaccuracy (memory) and expertise requirement for oral transmission and printing solved the the errors, limited volumes, and cost of hand copying. Now, digital materials address the rising costs of books, which take years to write or update, do not allow searching or interactive processes, and are forced to serve a variety of learning and teaching styles. "The traditional book does a good job of aiding the memory of people and of preserving the hierarchical organization. It does less of a good job of presenting connections or links or of allowing easy searching, both of which the brain does routinely." (Burrus 2007, 21)

Inputs Innovations

Incremental innovations in the publishing industry between 1967 and 1987 focused on "new capital expenditures" looking to advance the business side of the firms; this included "computer systems for editing, data management, accounting, royalties, and payroll" (Greco 1997, 3).

Custom Publishing and Bundled Textbooks

"Customization of print textbooksâlike changing the number of chaptersâand incorporating digital tools such as assessment and work problems, are becoming more commonplace, which is changing the substance of what constitutes a textbook" (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 10). "Custom publishing is considered to be of value in retarding the preference of used books because materials tailored to specific courses do not travel well beyond the courses. The migration to technology also is seen as valuable because of the tailoring that can occur and because much of what is offered digitally is time-sensitive to the length of the course." (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 12) Similarly, publishers are creating textbook bundles to be sold for each class, which would "include coursepacks and electronic media and accounted 16% of all textbook sales in 2007". (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 11) Unfortunately, according to the findings of a 2005 GAO report, "[w]hile many factors affect textbook pricing, the increasing costs associated with developing products designed to accompany textbooks, such as CD-ROMs and other instructional supplements, best explain price increases in recent years. Publishers say they have increased investments in developing supplements in response to demand from instructors. Wholesalers, retailers, and others expressed concern that the proliferation of supplements and more frequent revisions might unnecessarily increase costs to students" (GAO 2005, 3).

Increased Frequency of Textbook Revisions

"Twenty or 30 years ago, textbook publishers would bring out a new edition of a successful textbook every four or five years; that would enable them to keep the book up to date and help ensure that they didn't lose market share to competing volumes. However, as the used-book market took off, publishers began to speed up the cycle of new editions to render earlier editions obsolete. Now the typical cycle for new editions of the most successful textbooks is two or three years." (Thompson 2005) The GAO report states, "one publisher [...] said that the current revision cycle at the company is tied to the pattern of sales revenues, which all publishers agreed decline the longer the textbook is on the market and more used copies become available" (GAO 2005, 19). (For a full, balanced discussion of this topic see pages 18-19 in the GAO report.)

Cheaper/Alternative Materials

Some textbook publishers are exploring cover-less books or hole-punched packages (Shamchuk 2009, 15).

Commons-based peer production

Only recently have we seen any evidence of commons-based peer production. One of Wikimedia's projects is Wikibooks, an attempt to do what Wikipedia did for the encyclopedia for textbooks. A notable and successful example of using this model for producing EM content is Connexions (detailed on Commons-based Cases in EM#Cases).

Outputs Innovations

Innovations in EM outputs are often tied to digital inputs innovations that allow for their feasibility. The most prominent innovations are e-Books and e-commerce web sites that connect independent buyers, sellers, and traders.

e-Books are a disruptive technology despite the fact that they represent a small percentage of EM sales. In 2005, "30,000-50,000 e-book units were in use in the United States"; "total e-book sales were in the $12 million range" (Greco 2007, 24). CourseSmart is a eTextbook web site that was founded and is supported by major textbook publishers (Pearson, Wiley, Cengage Learning, McGraw-Hill Education, Bedford, Freeman, and Worth Publishers, and Jones and Bartlett Publishers) to provide e-Book content to be sold through a standard system.

A number of start-up EM publishers (see Alternative Business Models in EM#Startups) are offering free textbooks supported by advertising on pages or through their online reading interface. Examples include BookBoon and Freeload Press. Textbook Media distributes Freeload Press books and other similar texts, offering free, advertising-supported and inexpensive, ad-free versions.

In the realm of traditional print textbooks, (computerized) print on demand is an incremental innovation that has "allowed publishers to keep titles 'in print,' effectively reaching new audiences for decades" (Greco 2007, 24). This is particularly effective for books in the public domain that might be required for academic purposes.

Another recent option, which has been explored at a number of public university campuses to lower the cost of textbooks for students, is textbook rentals. A few e-commerce sites have emerged to address this potential market: Chegg, [Campus Book Rentals, and BookSwim.

Industry Market Profile

Book Publishing Industry

The 2006 U.S. Census Data (U.S. Census Bureau, Company Statistics Division & Bowan 2008) presented 3,042 publishing firms, with 83,504 employees and annual payroll of $4,993,924 in the book publishing industry, of which textbook firms are part.

| Year | # of Firms | # of Employees | # Annual Payroll | Shipments Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | 1,022 | 52,000 | $390 million | $2.13 billion |

| 1987 | 2,298 | 70,100 | $1.86 billion | $11.6 billion |

| 2006 | 3,042 | 83,504 | $5 billion | ??? |

Specifically, the "market share for new textbooks (that is, the $4.2 billion segment) is highly consolidated, with 6 publishers holding about 85% of all sales dollars (Pearson, Thomson, McGraw Hill, John Wiley, Houghton Mifflin, and St. Martin's/Von Holtzbrinck). Although college publishing remains highly profitable for the large players, with reported EBITDA in some instances as high as 30%, growth has stalled, due in large part to the rise of the used book business, which represents the key strategic issue in the industry today." (Esposito 2005, 2)

In terms of sales, actors in the educational materials sector were responsible (by type of book) for (Source: Book Industry Study Group 2005):

- Professional and scholarly: $4.1 billion (176 million units)

- University press: $450 million (24 million units)

- Elhi (elementary and high school texts): $4.7 billion (178 million units)

- College textbooks (all levels): $3.9 billion (67 million units)

Higher Education EM Industry Data

In 2005, Esposito estimates that the college book market is around $7 billion, based on $4.2 billion in net annual revenues to publishers for new textbooks, plus the approximately $1.2 billion used book trade and "all the books that are not formal textbooks that find their way into the curriculum, mostly in the humanities: literary classics, paperbacks on social policy, anthologies, coursepacks (collections of readings), etc." (Esposito 2005, 2).

According to Simba Information, in 2007 "textbooks and other materials sold into the college market generated an estimated $8.93 billion in net sales, up 7.6% from $8.3 billion in 2006" and projected growth (calculated before the recession) of these materials was "$9.42 billion in 2008, up 5.5%" (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 1). At 39.4%, the largest component of the market was still new textbooks, however this was "off 0.4% from the estimated 39.8% share in 2006"; and despite below average sales in December 2007, net sales growth for 2007 was 6.5% to "an estimated $3.52 billion" (ibid.). Digital materials, defined as "digital content tools for assessment and homework assistance, and multimedia materials, sold separately from textbooks", is one of the fastest-growing segments up 7.9% from 2006 to $300 million and was projected to increase 13.2% to $339.5 million in 2008 (ibid.).

"Total college book unites--an estimated 118.2 million--sold at retail in 2007 were down 2% from 2006, driven by a decline of 8.5% in new-book unites to an estimated 74.1 million units, while used-book unites increased 11.4% to 44.1 million" (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 2). As of June 2007, the average new textbook retail price was $74.88, up approximately 60 cents (0.9%) from 2006. "Overall, between 2003 and 2007, the average price increase for new textbooks was 3.2%" (ibid.). Medical Sciences and Business texts showed the strongest retail sales growth in 2007.

The most dominant college publisher continued to be Pearson in 2007, with 6% revenue growth to an estimated $1.21 billion, which the company attributed to "investment in established and new author franchises, helped by continued strong double-digit growth in custom solutions" (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 2).

Based on expected college enrollment growth and greater "acceptance of digital materials", Simba Information forecasted a 7.4% compound annual growth for the industry or "a combined total of $7.95 billion" through 2011 (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 3).

These figures can be put in perspective of Thad McIlroy's estimate of the entire educational materials field; taking into account the consistently heavy use of printed publications by most educational institutions, he suggests the "combined print publishing business for the education industry is worth in the range of $20 billion per year in North America [...], this could represent some 50% of total book sales (unlikely, but defensible from published data)" (McIlroy 2008).

Public Policy Affecting Higher Education EM

National Legislation

H.R. 1464: Learning Opportunities With Creation of Open Source Textbooks (LOW COST) Act of 2009

- Status: Introduced by Rep. Bill Foster on March 12, 2009, referred to committee

- Full text of the Bill: http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=h111-1464

- Provisions of the Bill:

- The LOW COST Act of 2009 would require certain federal agencies to collaborate and develop freely available open source educational materials for college-level math and science subjects. ('Foster Introduces Bill to Reduce Cost of College Textbooks' 2009) Heads of federal agencies that expend more than $10,000,000 annually on scientific education and outreach would be required to use at least two percent of those funds to develop and implement open source materials as an educational outreach effort. The materials would be made available free of charge on a new “Federal Open Source Material” Web site, where they could be downloaded, redistributed, changed, and revised by any member of the general public. (ibid.) The head of each affected agency would be required to develop, implement, and establish procedures for checking the veracity, accuracy, and educational effectiveness of the materials. At a minimum, the materials would contain a comprehensive set of textbooks or other educational materials covering topics in college-level physics, chemistry, or math; be updated annually; and free of copyright violations. The bill would authorize $15,000,000 in appropriations for the purpose of awarding grants to educational institutions, nonprofit or for-profit organizations, and federal agencies that produce the materials. (ibid.)

S. 945 [110th]: College Textbook Affordability Act of 2007

- Status: Introduced by Sen. Dick Durbin in March 20, 2007, never became law

- Full text of the Bill: http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=s110-945

State Legislation

Common Policy Themes

- click on links to see lists of relevant proposed and passed legislation from 2004-2007 (ACSFA 2007)

- Sales tax exemption for textbooks

- also includes income tax credits for EM purchases

- Require faculty to consider costs of educational materials

- Regulate educational materials that have particularly limited re-usability

- Require publishers and/or bookstores to offer unbundled textbooks in addition to bundles for particular courses

- Require publishers to disclose info on textbooks’ wholesale prices and revision histories

- Reduces sales of new textbooks by publishers

- Recommend that institutions explore alternative textbook sources or otherwise innovate to reduce costs of educational materials

- e.g. textbook rental programs

- Regulate textbook prices in public institutions

- Commission studies and reports to investigate high cost of textbooks

- Good to follow up on and see state findings for those studies that were actually carried out

- Require schools/bookstores to actively promote textbook buyback programs

- Represents used book competition for publishers

Potentially Key Legislation

AB 2477 (CA)

- Signed into law 9/16/04 (ACSFA 2007, 2)

- Provisions of the Bill

- “Encourages publishers to unbundle textbooks; reveal price info on textbooks, differences between editions, and planned length of circulation of current edition; and update current editions with supplements rather than the creation of new editions

- "Requests the UC system and requires CSU and CCC systems to encourage faculty, through the academic senate, to consider low cost textbooks, work w/ publishers to create cost-effective bundles, inform students of book costs and differences between editions, and evaluate the system of how faculty notify the campus bookstore of textbook selection

- “Requests the UC system and requires CSU and CCC systems, though the academic senate, to evaluate the current system of communication between faculty and the campus bookstore

- “Requires campus bookstores to publicly list textbook costs for each course

- “Urges schools to give students as many options as possible for purchasing textbooks”

HB 1024 (CO)

- Signed into law 6/1/06 (ACSFA 2007, 4)

- Provisions of the Bill

- “Requires the governing board of each state college and university to consider creating an online textbook library for students in an effort to reduce the cost of college textbooks; these schools are not required to create this library, only to consider it; no other information is provided”

AB 1214 (NY)

- Introduced 1/19/05 (ACSFA 2007, 13)

- Provisions of the Bill

- “Amends the education law to broaden the definition of textbooks to include supplementary books, fiction, non-fiction, manipulatives, art reproduction, maps, sheet music, manuals, almanacs, atlases, general dictionaries, encyclopedias, magazines, and newspapers”

Production and Costs in EM

Production Process

Costs of Production

Despite the lack of transparency in terms of textbook production costs, when analyzing financial reports of publishing industries in this sector, the National Association of College Stores created a schematic to illustrate (and defend) the sources (as percentages of each dollar) of contemporary textbook costs: Where the New Textbook Dollar Goes.

Demand Structure in Higher Education

New Textbooks

Professors Choose but Students Buy

Dr. James Koch, in a 2006 report on the textbook market, remarks: "The textbook market is remarkable because the primary individuals who choose college textbooks (faculty) are not the people that pay for those textbooks (students). Only a few other organized markets in the United States are similar in this regard. A comparable situation exists in medicine where doctors prescribe drugs for their patients, but do not pay for those drugs. Analogous to the market for prescription drugs where prices have risen rapidly, in the market for textbooks the separation of textbook choice and textbook payment profoundly influences pricing. Albeit for primarily good purpose, students end up being coerced to pay for someone else’s choices. This tends to make their textbook purchases less responsive to price increases than their purchases of items such as cheeseburgers and jeans." (Koch 2006, 2)

Demand-driven Innovation

In a 2008 Simba Information report, Macmillan president Brian Napack reflects, "The market is migrating very steadily online because the customer--meaning the students and professor--demands it" (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 8).

Used Books/Textbooks

Publisher revenues have been affected with the growth of the used book market, particularly for editions of college textbooks that are used across multiple terms or even years. Students demand used books to cut costs and although "[c]ollege bookstores may be the primary venue for sales of new textbooks, [...] the stores actively promote the sale of used textbooks as one of their key revenue drivers" (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 12). Beyond traditional bookstore models, online book swapping has proliferated to meet the demand for used textbooks. As the Simba Information report states, "[t]he Internet facilitates accessibility to used textbooks across the geographical boundaries of college campuses; home-grown textbook swapping sites, again on the Internet, also contribute to the trade of used books" (Mickey and Meaney 2008, 12).

Bibliography for Item 2 in EM

Back to The Higher Education Level

Back to Educational Materials

Back to Report April 2009#Educational Materials