Diagnostic Kits/Old notes IP

Introduction

(ADDED TO PAPER)

The results of a study carried our by Jensen and Murray shows “20% of human genes are explicitly claimed as U.S. IP” (Jensen, K. & Murray, F., 2005). The study also found that the patent coverage is not evenly distributed. “Although large expanses of the genome are unpatented, some genes have up to 20 patents asserting rights to various gene uses and manifestations including diagnostic uses, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), cell lines, and constructs containing the gene” (Jensen, K. & Murray, F., 2005).

Merz claims market structure is primarily influenced by "the number of patents related to a test", "the simplicity of a test may favor pure competition", and "prevalence of a disease or condition." (Merz, J.F., 1999) Merz is most concerned with the effect of patents on the market structure. (Merz, J.F., 1999)

"Several reports from national and international bodies note that genetic testing applications require far less investment after initial gene discovery than development of therapeutic proteins, and so the rationale for exclusive intellectual property rights may be less compelling." (Pressman, L. et al., 2006)

When IP does work

(ADDED TO PAPER)

- The perception of rising patent litigation rates in the area of DNA-based patents is most likely false

- Rising litigation costs are perceived to be hurting litigation. The Mills article argues there is little empirical evidence supporting this position. (Mills, A.E. & Tereskerz, P., 2008)

- This article gives the findings of a “small empirical study of DNA-based litigated patents to determine whether or not rates of litigation on DNA based patents are actually increasing” (Mills, A.E. & Tereskerz, P., 2008). The study found that the rate of litigation involving genetic patents has decreased in recent years. “Between 2000 and 2005, the rate of patent litigation for the patent classifications studied dropped significantly from 14/3,827 to 1/2,772” (Mills, A.E. & Tereskerz, P., 2008).

- There has been "an increase in patents on the inputs to drug discovery (“research tools”)." (Cohen et. al., 2003)

- no substantially barriers have been found as a result of this increase in patents on the inputs to drug discovery

- no substantially barriers found to university research

- THE EXCEPTION: "Restrictions on the use of patented genetic diagnostics, where we see some evidence of patents interfering with university research, are an important exception. There is, also, some evidence of delays associated with negotiating access to patented research tools, and there are areas in which patents over targets limit access and where access to foundational discoveries can be restricted. There are also cases in which research is redirected to areas with more intellectual property (IP) freedom. Still, the vast majority of respondents say that there are no cases in which valuable research projects were stopped because of IP problems relating to research inputs." (Cohen et. al., 2003)

When IP doesn't work

(ADDED TO PAPER)

Summary of the Risks Associated with Patent Protections of Genetic Testing

Data Access

- Searching for genetic patents is difficult. Solutions have arisen in the form of topic specific databases. (Verbeure, et al., 2005)

Bayh-Dole

- The Bayh-Dole Act may not be serving its purpose in the genetic testing context. If genetic research is inhibited by patenting behaviors then the fact that at least one study found “[t]he majority of the patent holders enforcing their patents were universities or research institutes, and more than half of their patents resulted from government-sponsored research” means that the act holds a central role in creating a barrier to access (Cho et al. 2003).

Patent Protection

- The rise of patent protections over genetic testing research may cause labs to decline to develop new tests and stop their current genetic test offerings. (Cho et al. 2003)

- Patenting of genetic testing can “increase the costs of genetic diagnostics, slow the development of new medicines, stifle academic research, and discourage investment in downstream R&D” (Jensen, K. & Murray, F., 2005)

- There is evidence that patents are not necessary for the quick transformation of the genetic markers to a clinical test (Merz, J.F. et al., 2002)

Licensing

- Licensing behavior can have a measurable effect on the development and performance of genetic testing laboratory studies. Many changes in ownership and degree of patent enforcement lead to market confusion, which has a chilling effect on new and current research. (Merz, J.F. et al., 2002) On the other hand, these licensing effects may actually be a decrease in market rather than effects of licensing behavior (Merz, J.F. et al., 2002)

Example:

- The ACLU Case (Association for Molecular Pathology, et al. v. United States Patent and Trademark Office, et al.)

- [Rights and Civil Wrongs: The ACLU Lawsuit]

- [Challenges Patents on Breast Cancer Genes]

- mutations: BRCA1 and BRCA2

- As a result of the PTO granting patents on the BRCA genes to Myriad Genetics, Myriad's lab is the only place in the country where diagnostic testing can be performed (ACLU Challenges Patents On Breast Cancer Genes)

- "Myriad's monopoly on the BRCA genes makes it impossible for women to access other tests or get a second opinion about their results, and allows Myriad to charge a high rate for their tests - over $3,000, which is too expensive for some women to afford." (ACLU Challenges Patents On Breast Cancer Genes)

- Obstacles to the lawsuits success: (Patent Rights and Civil Wrongs: The ACLU Lawsuit)

- genes are considered patentable subject matter (see Diamond v. Chakrabarty).

- Standing: "none of the plaintiffs who sued Myriad have themselves been sued for infringing Myriad’s patents." (Patent Rights and Civil Wrongs: The ACLU Lawsuit)

When IP doesn't matter

Academic Research versus Private Research: relation between freedom of research and openness

(ADDED TO PAPER)

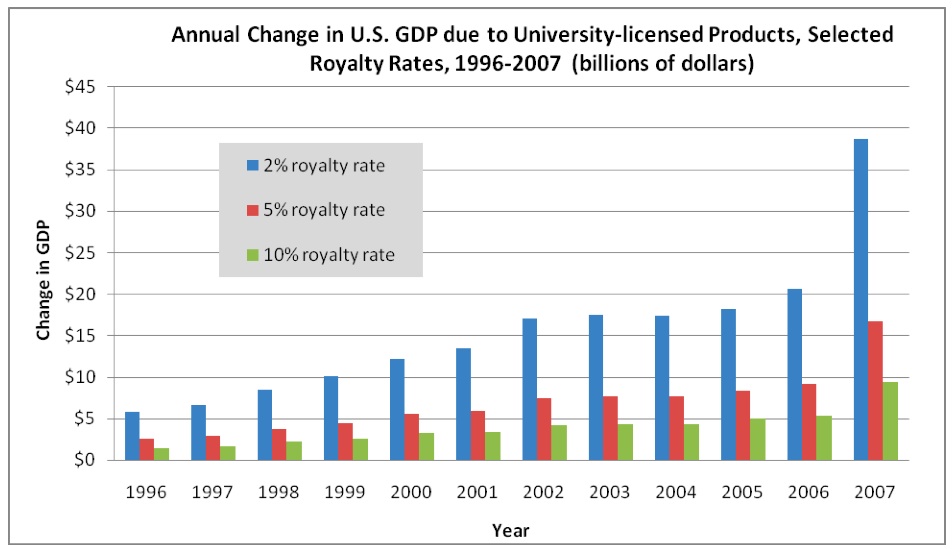

- The study of university technology licensing from 1996 to 2007 shows a $187 billion dollar positive impact on the U.S. Gross National Product (GNP) and a $457 billion addition to gross industrial output, using very conservative models. (Source: Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO))

- study was funded by BIO

- study was headed by Dr. David Roessner, Professor of Public Policy Emeritus at the Georgia Institute of Technology

- "BIO also released today a survey of its member companies which shows that university-based technology transfer serves as a foundation for the creation of many biotechnology companies and industry job growth. Half of surveyed companies were founded on the basis of obtaining an in-license agreement with significant, subsequent job growth." (Source: Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO))