(Footnotes fixed, 4/1/99)

Reference: This is an essay-in-progress.

The original version was published in New Light on a Dark Age: Exploring the Culture of Geometric Greece, ed. Susan Langdon (Columbia: U. of Missouri Press 1997) 194-207.

(Footnotes fixed, 4/1/99)

Reference: This is an essay-in-progress.

The original version was published in New Light on a Dark Age: Exploring the Culture of Geometric Greece, ed. Susan Langdon (Columbia: U. of Missouri Press 1997) 194-207.

Homer critics have begun to interpret the resolution of the Iliad in Book 24, at the end of the epic, as a reflection of a new spirit that emerges from the heroic tradition and culminates in the ethos of the City State or polis.(1) A sign of this ethos is the moment when Achilles, following his mother's instructions to accept the apoina or 'compensation' offered by Priam for the killing of Patroklos by Hektor (Iliad 24.137), is finally moved to accept the apoina (24.502) and consequently to release the corpse of Hektor for a proper funeral, thereby making possible his own heroic rehumanization.(2) I propose that the ethos leading toward a resolution at the end of the Iliad is already at work inside the very structure of the Iliad. Though the rules of Homeric poetry seem incompatible with overt references to the values of the polis, the poetry itself draws attention to this incompatibility in the timeless and even limitless picture of the City at War and the City at Peace, depicted in the hero's own microcosm, the Shield of Achilles in Iliad 18.(3)

In describing this picture as "limitless," I have in mind an essay of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, originally published in 1766, the title of which has been translated into English as Laocoön: An essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry. I draw attention not only to the use of the word limits in this title but also to the emphasis placed by Lessing on the limitlessness inherent in one particular detail of the picture, that is, a scene of a litigation that is taking place in the City at Peace.(4) In painting a picture through poetry, Lessing argues, the poet chooses not to confine himself to the limits of the art of making pictures. And yet, as we will see, the picturing of this particular detail of a litigation allows "the poet" to go beyond the limits of his poetry as well. That is, the Iliad need not end where the linear narrative ends, to the extent that the pictures on the Shield of Achilles leave an opening into a virtual present, thus making the intent of the Iliad open-ended.(5)

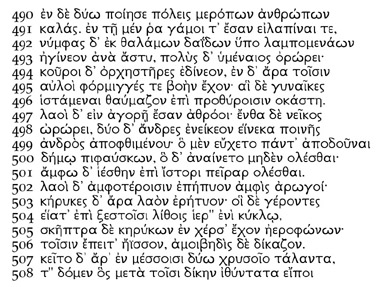

Let us take a close look at this detail on the Shield of Achilles, picturing a litigation that is taking place in the City at Peace:

490 On it he [= the divine smith Hephaistos] wrought two cities of mortal men. 491 And there were weddings in one, and feasts. 492 They were leading the brides along the city from their maiden chambers 493 under the flaring of torches, and the loud bride song was arising. 494 The young men were dancing in circles, and among them 495 the pipes and the lyres kept up their clamor as in the meantime the women, 496 standing each at the door of the courtyard, admired them. 497 The people [laos] were gathered together in the assembly place, and there a dispute [neikos] 498 had arisen, and two men were disputing [neikeô] about the blood-price [poinê] 499 for a man who had died [apo-phthi-]. The one made a claim [eukheto] to pay back in full, 500 declaring publicly to the district [dêmos], but the other was refusing to accept anything. 501 Both were heading for an arbitrator [histôr], to get a limit; 502 and the people [lâos] were speaking up on either side, to help both men. 503 But the heralds kept the people [lâos] in hand, as meanwhile elders 504 were seated on benches of polished stone in a sacred [hieros] circle 505 and took hold in their hands of scepters [skêptron] from the heralds who lift their voices. 506 And with these they sprang up, taking turns, and rendered their judgments [dik-azô],(6) 507 and in their midst lay on the ground two weights of gold, 508 to be given to the one among them who pronounced a judgment [dik-ê] most correctly.

Iliad 18.490-508

This juridical scene, I propose, lays the conceptual foundations for the beginnings of the polis, even though the telling of the scene itself is framed by an epic medium that pretends, as it were, that there is as yet no polis.(7) Despite this pretense, the existence of the polis is indirectly acknowledged in the image of an inner circle of elders who surround the scene, debating the rights and the wrongs played out in the juridical proceedings, and in the image of an outer circle made up of "the surrounding crowd," who "decide which elder wins the award"--to return to line 508. In using these words to describe the juridical scene in the City at Peace, I am following the interpretation of Mark Edwards in his commentary on Iliad Books 17-22,(8) who cites analogies to this description of early Greek law in early Germanic law.(9)

Edwards' Iliad commentary is helpful in giving basic bibliography and summaries of critical interpretations of the Shield of Achilles passage, including the litigation scene,(10) but I think that he has not done full justice to the research of Leonard Muellner on this passage.(11) Muellner studies the use of eukhomai in Iliad 18.499, a verse from the passage quoted above, and he stresses that this verse contains the only overt literary attestation of this word in a juridical context--a context confirmed by the evidence of the Linear B tablets. He notes the reference to a juridical procedure in one of these tablets:

text as transliterated from the Linear B syllabic script e-ri-ta i-je-re-ja e-ke e-u-ke-to-qe e-to-ni-jo e-ke-e te-o da-mo-de-mi pa-si ko-to-na-o ke-ke-me-na-o o-na-to e-ke-e Greek text as reconstructed from the syllabic script(12) e-ri-ta hiereia ekhei eukhetoi-kwe e-to-ni-jo ekheen theôi; dâmos de min phâsi ktoinâôn kekeimenâôn onâton ekheen

translation 'e-ri-ta the priestess has and makes a claim [eukhetoi-kwe] to have e-to-ni-jo-land on behalf of the god; but the dâmos says that she has, from the landholdings [= ktoinai] that are common,(13) a holding-in-usufruct [= onâton] .' Pylos tablet Ep 704

Let us review the corresponding words in the Iliad 18 passage quoted above:

497 The people [laos] were gathered together in the assembly place, and there a dispute [neikos] 498 had arisen, and two men were disputing [neikeô] about the blood-price [poinê] 499 for a man who had died [apo-phthi-]. The one made a claim [eukheto] to pay back in full, 500 declaring publicly to the district [dêmos], but the other was refusing to accept anything.

I repeat, Muellner stresses that this Homeric passage is the only overt literary attestation, in all of Greek literature, where this word is found in a juridical context--a context confirmed by the evidence of the Linear B tablets.

Following Muellner's analysis, Raymond Westbrook published an article analyzing Near Eastern parallels to the evidence of the Homeric and the Linear B juridical contexts.(14) Also, he made an adjustment on Muellner's interpretation of the Linear B text (the translation that I have just given reflects this change), and, by extension, of the Homeric text as well. Westbrook points out that the priestess mentioned in the Linear B tablet may be making a claim to the right of landholding, not necessarily to the fact of landholding.(15) Let us look at the wording again:

'e-ri-ta the priestess has and makes a claim [eukhetoi-kwe] to have e-to-ni-jo-land on behalf of the god; but the dâmos says that she has, from the landholdings [= ktoinai] that are common, a holding-in-usufruct [= onâton] .'

By extension, Westbrook argues that the defendant in the scene of litigation on the Shield of Achilles is likewise claiming the right to pay poinê or 'compensation' in full for the death of the man mentioned in verse 499 of Iliad 18. Let us look at the wording again:

499 The one made a claim [eukheto] to pay back in full, 500 declaring publicly to the district [dêmos], but the other was refusing to accept anything.

Presumably the defense contends that the man did not die as a result of aggravated murder, and that there were mitigating circumstances. Comparing the evidence of analogous Near Eastern juridical documents, Westbrook postulates "(a) that the ransom [that is, compensation] would be fixed by the court, in accordance with the objective criteria of traditional law" and "(b) that the basis for such a claim by the killer would be that the case is one of mitigated homicide."(16)

In making his arguments, Westbrook adduces a variety of parallels, from which I select the following:

In short, following Westbrook, I think that the rationale of the litigation scene on Achilles' Shield is basically this: the defendant wishes the limit to be ransom, not revenge, while the plaintiff wishes the limit to be revenge, not ransom.(24) I draw attention to my use of the word limit, which corresponds to the juridical sense that we are about to examine in Iliad 18.501, in the picture of the litigation scene in the City at Peace. In what follows I will try to connect a juridical sense of limits with a poetic sense of limits, in pursuing my general argument that the picture of the litigation scene allows "the poet" to go beyond the limits of his poetry.

Let us take an even closer look at the litigation scene in the City at Peace:

497 The people [laos] were gathered together in the assembly place, and there a dispute [neikos] 498 had arisen, and two men were disputing [neikeô] about the blood-price [poinê] 499 for a man who had died [apo-phthi-]. The one made a claim [eukheto] to pay back in full, 500 declaring publicly to the district [dêmos], but the other was refusing to accept anything. 501 Both were heading for an arbitrator [histôr], to get a limit; Iliad 18.497-501

The defendant is expounding his case to the dâmos, as we see from line 500, and Leonard Muellner makes it clear that the same word, dâmos, which must be interpreted as 'district' or 'community', functions in the Linear B documents as a legal entity in its own right.(25) Raymond Westbrook finds this step in Muellner's argument crucial.(26) I should add that Muellner's argument here is strengthened by the methodology that he applies to his detailed analysis, which combines historical linguistics as perfected by Antoine Meillet and Emile Benveniste with formulaic analysis as pioneered by Milman Parry and Albert Lord. Muellner stresses that Michel Lejeune, another historical linguist, defines the dâmos in the Linear B tablets as an administrative entity endowed with a juridical function.(27) In other words, the dâmos can be seen as a prototype of the polis.(28)

Let us turn back to the Iliad commentary of Mark Edwards: he interprets verses 499-500 of Iliad 18 as follows: "The one man was claiming <to be able, to have a right> to pay everything (i.e. to be free of other penalties), the other refused to accept anything (i.e. any pecuniary recompense in place of the exile or death of the offender)."(29) He goes on to say on the same page: "After I had formulated the above views, R. Westbrook was kind enough to show me his article on the trial scene (forthcoming in HSCP)."(30) Westbrook's 1992 article is then summed up this way by Edwards:

Westbrook therefore holds that in this trial scene the killer is claiming the right to pay ransom (poinê, 498) in full (panta, 499) on the grounds of mitigated homicide, the amount to be fixed by the court. The other party is claiming and choosing the right to the revenge, as in cases of aggravated homicide. The court must set the 'limit' (peirar, 501) of the penalty, i.e., whether it should be revenge or ransom and also the appropriate 'limit' of either revenge or ransom. This view is identical with my own, and in accordance with the usual meaning of peirar.(31)

Again I focus on the word peirar 'limit' at verse 501 of the Shield passage. I find the meaning of peirar, the limit of the case, significant in terms of the physical visualization of an inner circle of elders who are attempting to define such limits. Moreover, there is an outer circle of people who are in turn attempting to define the best definition of such limits. In terms of a linear narrative, the peirata or limits of the Iliad would be the end of the Iliad, when Achilles finally accepts the apoina or compensation. In terms of the concentric circles that surround the scene of litigation in the Shield of Achilles, on the other hand, the peirata or limits of the Iliad would be the outermost limits of the Iliad, that is to say, the broadest possible interpretive community.

We must return presently to this notion of a broadest-based audience for the Iliad. The point for now, however, is that I agree with Edwards concerning the peirata or 'limits' of the litigation in the Shield of Achilles passage. And I should add, if I may follow through on my own sense for setting the record straight, that Muellner deserves far more credit than Edwards gives him for his contributions to our understanding of the litigation scene in the Shield. Edwards objects to Muellner's seemingly interpreting the claim of the defendant at Iliad 18.499 as a fact of paying rather than a right to pay, and he cites with approval the earlier work of J.-L. Perpillou, who had also cited the evidence of Linear B eukhomai and who translates the Homeric eukhomai at 18.499 in terms of the defendant's claiming a right, not a fact.(32) But Edwards here has not followed through on Muellner's overall interpretation, which goes beyond the immediate context of the two litigants on the Shield--and which certainly goes beyond the objectives of Perpillou, who stresses simply the juridical force of both the Linear B and the Homeric eukhomai.(33) As Muellner says clearly about the context of eukhomai at 18.499, "the issue is not whether the fine was actually paid."(34) Rather, as he makes it quite clear, the issue is whether the plaintiff is morally obliged to accept the payment.

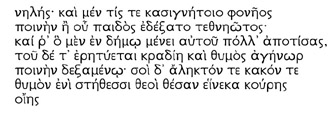

It is in this context that Muellner cites the words of Ajax to Achilles in Iliad 9:(35)

Pitiless one! A man accepts from the slayer of his brother a blood-price [poinê], or for a son that has died; and the slayer remains in his own district [dêmos], paying a great price, and his [= the kinsman's] heart and proud spirit are restrained once he accepts the blood-price [poinê]. But for you it was an implacable and bad spirit that the gods put in your breast, for the sake of a girl --just one single girl! Iliad 9.632-639

We may compare the wording in the Shield passage:

499 for a man who had died [apo-phthi-]. The one made a claim [eukheto] to pay back in full, 500 declaring publicly to the district [dêmos], but the other was refusing to accept anything.

Iliad 18.499-500

Edwards also cites this Iliad 9 passage, though he credits not Muellner's 1976 monograph but an article published by Øivind Andersen in the same year.(36) Andersen too compares the Iliad 9 passage, concerning the acceptance of poinê; further, he cites the same Iliad 24 passages cited by Edwards and mentioned by me at the beginning of my essay, concerning the acceptance of apoina by Achilles at the end of the Iliad (24.137, 502). Still, in order to set the record straight, I must note an important difference between Muellner's interpretation and Andersen's--the one chosen by Edwards--concerning the litigation passage. In the words of Keith Stanley, Andersen's interpretation is "against strict design."(37) By this, Stanley means that Andersen finds the Iliad 9 passage--as also the Iliad 24 passages--useful for understanding the Iliad 18 passage concerning the litigation, but not necessarily vice versa. The position taken by Edwards in his Iliad commentary closely resembles that of Andersen.(38) For Muellner, by contrast, the communication between the tenor or the framing structure and the vehicle or the framed structure is not one way but both ways.(39) Just as the logic of a simile spills over into the logic of the narrative frame, so also the logic of the story-within-a-story, the litigation scene, spills over into the logic of the story of Achilles, affecting all other passages. From Muellner's point of view, you cannot say that you "solved" the meaning of the litigation scene if you disregard its relation to the main narrative.

From the standpoint of the Iliad as a linear progression, there is a sense of closure as the main narrative comes to an end in Book 24. From the standpoint of the Shield passage, however, the Iliad is open-ended. In other words, the vehicle re-opens the tenor. In order to make this argument, I must first confront a paradox: the world as represented on the Shield seems to be closed and unchanging, as opposed to the openness of the Iliad to changes that happen to the figures in the story while the story is in progress. The question is, however, what happens when the story draws to a close? Now the figures inside the Iliad become frozen into their actions by the finality of what has been narrated. This freezing is completed once all is said and done, at the precise moment when the whole story has been told. This moment, which is purely notional from the standpoint of Iliadic composition, gets captured by the frozen motion picture of the Shield. Time has now stopped still, and the open-endedness of contemplating the artistic creation can begin.

Our case in point is the scene of the litigants in the City at Peace: Muellner argues that the syntax of mêden 'nothing' at Iliad 18.500 makes it explicit that the miniature plaintiff in the picture will absolutely never accept any compensation.(40) Such a notional moment must be distinguished, however, from the real moments of the narrative in progress: later, in Book 19, soon after the description of the Shield, Achilles himself will in fact accept compensation from Agamemnon for the loss of Briseis.(41) Still later, in Book 24, he will accept compensation from Priam for the death of Patroklos. And yet, from the synoptic standpoint of the Iliad writ large, as it were, Achilles remains utterly inflexible in refusing compensation--for the ultimate loss of his own life.(42)

In order to pursue this point, I focus on an instance of textual variation at Iliad 18.499 between apophthimenou 'a man who died' and apoktamenou 'a man who was killed'. The second variant, as we learn from the scholia, was noted by Zenodotus. If indeed the Shield passage, as a vehicle, can refer to the main narrative of the Iliad as the tenor, then the referent of this variant apoktamenou can be Patroklos, as suggested by Iliad 24 where Achilles accepts the apoina or compensation from Hektor's father Priam for the death of Patroklos.(43) If Patroklos is the referent, this variant can also bring an ulterior meaning into the Ajax speech in Iliad 9: Achilles is justified in refusing compensation or apoina in the Embassy Scene of Iliad 9 because, in the long run, the compensation in question concerns the death of Patroklos, not the loss of Briseis.(44) In the long run, Agamemnon has a share in causing the death of Patroklos and is therefore justified in offering compensation for it.

In the longer run, however, it was Achilles himself who caused the death of Patroklos, since he could not in good conscience accept the compensation of Agamemnon for Briseis--and since Patroklos consequently took his place in battle.(45) In the longer run, then, Achilles can be a defendant as well as a plaintiff in a litigation over the death of Patroklos.(46) In the longest run, though, Achilles can even be the victim himself, since the Iliad makes his own death a direct consequence of the death of Patroklos.(47) No wonder the plaintiff of the Shield scene will not accept compensation: potentially, he is also the defendant and even the victim! In this light, it becomes hard for the narrative to say that anyone is liable for killing Achilles. It becomes easier now to think of the hero not as apoktamenou 'a man who was killed' but as apophthimenou 'a man who died'.

Earlier, I made the claim that, just as the logic of a simile spills over into the logic of the narrative frame, so also the logic of the story-within-a-story, the litigation scene, spills over into the logic of the story of Achilles. But there is more to it: it spills over even further, into the logic of the supposedly impartial elder adjudicators who compete with each other about who can best define the rights and wrongs of the case:

In the separate world of the Shield of Achilles, a group of arbitrators must compete with each other in rendering justice, until one winning solution can at last be found. Such a winning solution is also needed for the Iliad as a whole, which does not formally take a position on who is aitios [guilty, responsible] in the narrative. The question is left up to a figure who is beyond the Iliad, that is, to the histôr [18.501], whose function it is to render dikê 'judgment'.(48)

The logic of the litigation scene reaches even further, beyond the supposedly impartial elder adjudicators who compete over the perfect definition of the rights and wrongs of the case. It spills over into the logic of an outer circle of people who surround the elders, the people who are waiting to hear the elders' definitions and who will then define who defines most justly. As Michael Lynn-George notices, however, the defining voice is an end that is anticipated but "is always still to come."(49) Lynn-George continues: "the process is a desire for a finality that is infinitely deferred."(50) In the end, then, the logic of the litigation scene spills over, paradoxically, into the logic of an ever-expanding outermost circle, that is, people who are about to hear the Iliad. These people, I argue, are to become ultimately the people of the polis.

This model of an open-ended Iliad, the limits of which are delimited, paradoxically, by the expanding outermost circle of an ever-evolving polis outside the narrative, is compatible with a historical view of Homeric poetry as an open-ended and ever-evolving process. In previous work, I have described this view of Homer in terms of an evolutionary model.(51) Such an evolutionary model cannot be pinned down, I think, to any single "Age of Homer." I suggest that we need not think of any single age of Homer, but rather, several ages of Homer.(52)

This evolutionary model is the lens through which I see the picture on the Shield of Achilles, with its concentric circles of limits expanding further and further outward.(53) I repeat what I said earlier, this time going one step further. The logic of the litigation scene spills over into the logic of a surrounding circle of supposedly impartial elder adjudicators who are supposed to define the rights and wrongs of the case. Next, the logic of this inner circle of elders spills over into the logic of an outer circle of people who surround the elders, the people who will define who defines most justly. Next, it spills over into the logic of the outermost circle, people who are about to hear the Iliad. These people who hear Homeric poetry, as I said, are to become the people of the polis. Ultimately, these people are even ourselves.

1Seaford 1994, especially p. 73, where the "narrative development" of the Iliadic ending is correlated with "the historical development of the polis." For narrative details reflecting the emerging institutions of the polis, cf. Scully 1990, especially pp. 101-102.

2Seaford pp. 69-71, 176-177; at p. 176, there is an important adjustment on the formulation of Macleod 1982:16 ("the value of humanity and fellow-feeling"). See also Crotty 1994, who argues that the ceremony of supplication that takes place in Book 24 of the Iliad creates an emotional effect so powerful--and so troubling--that it will take another epic, this time, the Odyssey, to follow up on its resonances.

3On the correspondences between depicted details on the Shield of Achilles and narrated details in the main narrative of the Iliad, see Taplin 1980. The detail that I am about to consider is not among the ones treated in that work. On the general topic of the poetics of ecphrasis in the Shield of Achilles passage, see Hubbard 1992 and Becker 1995.

4Lessing 1962 [1766] Chapter 19 pp. 99-100.

5Cf. Hubbard 1992:17: "we do not see the shield as a finished product (for no man save Achilles can dare look upon it), but we see it in the process of fabrication by Hephaestus, as he adds ring after ring." Cf. Becker 1995:121; also Lynn-George 1988:49, 183-184 (whose valuable formulations will be discussed further below).

6On the juridical background for the notion that a speaker is authorized to speak by holding a skêptron, see Easterling 1989:106, with specific reference to this passage in Iliad 18.

7Cf. Seaford 1994:25: "the world on the shield seems to represent the everyday life of the audience, including a city at peace, as a contrast to the heroic world of the main narrative, in which there is no judicial mechanism to resolve the crisis of reciprocity."

9Edwards p. 214; on the Germanic comparanda, see Wolff 1946, especially pp. 44-46.

10Edwards pp. 212-218. See also Hubbard 1992:29-30, Becker 1995:119-123.

12Where the reconstruction is uncertain, I leave the text as transliterated from the syllabic script.

13Hooker 1980:139 thinks that ke-ke-me-na ko-to-na is common land "leased" from the dâmos.

17Westbrook p. 58; highlighting mine.

18Translation after Westbrook p. 57; highlighting mine.

19Translation after Westbrook p. 58.

21Translation after Westbrook pp. 61-62.

27Muellner 1976:104, citing Lejeune 1965:12.

32Edwards p. 215, citing Perpillou 1970:537; Westbrook 1992 did not use the work of Perpillou.

36Edwards 1991:216, citing Andersen 1976.

39Muellner 1990, applying the terms tenor and vehicle as used by I. A. Richards, 1936.

42Here I disagree with the reasoning of Lowenstam 1993:100 n. 103.

43My use of the word "referent" implies various degrees of cross-referencing in Homeric composition. See HQ 82: "It is from a diachronic perspective that I find it useful to consider the phenomenon of Homeric cross-references, especially long-distance ones that happen to reach for hundreds or even thousands of lines: it is important to keep in mind that any such cross-reference that we admire in our two-dimensional text did not just happen one time in one performance--but presumably countless times in countless reperformances within the three-dimensional continuum of a specialized oral tradition. The resonances of Homeric cross-referencing must be appreciated within the larger context of a long history of repeated performances."

45PH 254 n. 29, especially with reference to Iliad 9.502-512.

53In terms of an evolutionary model, the variant noted by Zenodotus at Iliad XVIII 499, apoktamenou 'a man who was killed' instead of apophthimenou 'a man who died' reflects a relatively earlier version of Iliadic narrative.