Existing Services

Human rights videos are currently disseminated through a variety of traditional and new media outlets. While these services have allowed many important human rights videos to reach an unprecedented audience, they are currently inadequate in two ways. First, none of the existing solutions have the proper alignment of incentives to support human rights media. Second, none of the services provide both secure anonymous uploading mechanisms and tools to ensure the anonymity of the videos’ subjects.

Alignment of Incentives

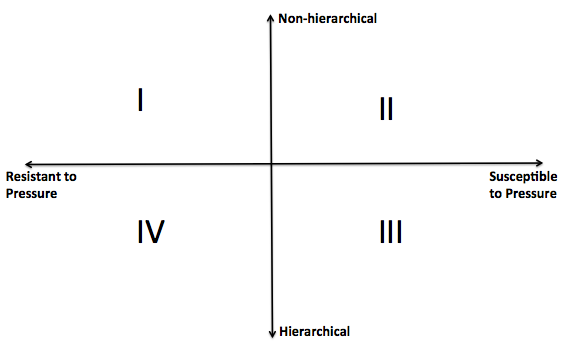

In order to explain why none of the current solutions have adequately solved the problems facing human rights media, it is helpful to plot these solutions using two important variables. First, the horizontal axis measures how susceptible these organizations are to government and financial pressures. Organizations that are more susceptible to pressure can be found on the right-hand side of the chart, while organizations that are resistant to these pressures reside on the left-hand side. Second, the vertical axis looks at the extent to which an organization filters the content it publishes. At the top, non-hierarchical organizations generally take a hands-off approach to the content available on their websites. Hierarchical organizations, on the other hand, exercise great control in the selection and promotion of human rights media. The basic chart is presented below.

Mapping the Competition

Second Quadrant

So what organizations currently fill this space? The second quadrant, in the upper right of the chart, includes for-profit, multinational organizations that host user-generated content. YouTube and Facebook are two popular organizations that fall directly into this quadrant.[1] Anyone with access can upload content on YouTube and publish it to the world, as long as it does not contain pornography or graphic violence.[2] Although YouTube is well-suited to host and disseminate large amounts of human rights media, it is still subject to outside pressures. Governments can force YouTube to limit the availability of certain content by threatening to block the site in their country. In 2008, for example, YouTube removed a controversial video critical of Islam in order to end Pakistan’s ban of the site.[3] Actions such as these demonstrate that sites like YouTube have a serious misalignment of interests and are not perfectly suitable to serve as publishers of human rights media.

Third Quadrant

Actors in the third quadrant also do not provide an ideal platform for promoting human rights media. This space is dominated by traditional news organizations such as the New York Times, CNN, Reuters, and the Associated Press. Although these organizations are subject to many of the same financial pressures as quadrant one organizations, they are generally less willing to cater to oppressive governments. The real problem with using these organizations to promote human rights media, however, is the hierarchical structure they use to select content. Many organizations lack a system by which users can send in their content for publication, forcing them use services like YouTube. Even if an organization does accept user-generated content, editors ultimately decide which information is worthy of the limited time or space they have to present the news. When these large news organizations cover human rights abuses, they often focus on countries where Western powers have some involvement.[4] As a result, important human rights media may not be chosen for publication.

Fourth Quadrant

The fourth quadrant contains most of the current human rights organizations., including Amnesty International and Witness.org. These groups are non-profit organizations with a dedicated focus on promoting human rights. Although governments can forcible remove these organizations, it will be more difficult to pressure them into compromising their ideological positions. Like CNN and the New York Times, however, quadrant four organizations all currently employ hierarchical methods for publishing human rights content, making value judgments about which content the world should see. Some organizations even chose to shoot their own footage of human rights events. Amnesty International, for instance, frequently publishes its own content gathered by affiliates rather than user-generated videos.[5] Additionally, organizations like Witness.org have shifted their focus away from curating and hosting human rights videos. The mission of Witness.org is now to encourage people on the ground to produce human rights videos by giving them access to equipment and training.[6]

A Gap in the First Quadrant

Existing organizations do a good job encouraging people to create human rights media and often bring these videos to the attention of the world, but we believe many of these videos are never seen. There is currently no viable organization for human rights media that is both resistant to pressure and non-hierarchical.

BitTorrent is a peer-to-peer file sharing protocol that exists in the first quadrant, but it is not a viable solution to the problems we have identified. First, it would be impossible to guarantee that all of the videos on a BitTorrent server were related to human rights, and these servers would likely be overrun by spam and other content. Second, in order to download content using BitTorrent, another user must be hosting that information. In countries with serious human rights abuses, Internet access may not be consistent or users may not wish to host the content for fear of being identified by the government. It will also be difficult to convince users to download videos in the first place, and then continue uploading them. If users stop uploading a video it can disappear from the torrent forever, whereas a video on Pharos would remain available forever. Third, there are simply not enough people on BitTorrent to make it an effective solution. While everyone has access to an Internet browser, BitTorrent requires additional software that most users will not be willing to install. Fourth, BitTorrent lacks an effective interface that would allow users to quickly browse and share important human rights videos. Thus, the effective and timely dissemination of human rights media will require something more than BitTorrent.

Additionally, the Hub was an offshoot of Witness.org that hosted user-submitted human rights media from 2007 to 2009, but it has since shut down. [7] While over 3000 videos remain on the site, no new videos can be uploaded.[8] This organization served an important function, and we believe Pharos should pick up where the Hub left off. Unlike the Hub, however, Pharos will anonymize all user-generated content and facilitate its publication on other popular news sites.

Pharos is therefore the only organization that will currently occupy the first quadrant. Pharos’ non-profit status leaves it immune to many of the tactics that governments have effectively used against profit-seeking companies. Additionally, the non-hierarchical nature of Pharos’ content publishing allows it to effectively disseminate human rights media and make it widely available.

References

- ↑ Other organizations might include Flickr, Vimeo, Veoh, and Metacafe.

- ↑ See YouTube Community Guidelines.

- ↑ See Greg Sandoval, Pakiston Welcomes Back YouTube, CNet (Feb. 26, 2008).

- ↑ For example, one study of the New York Times found that "[a]ttention to abuses occurs primarily in countries that were strategically instrumental during the cold war and in countries where there is clear U.S. involvement." See Caliendo et al., All the News That's Fit to Print? New York Times Coverage of Human-Rights Violations.

- ↑ See Amnesty International Video and Audio. Most of the videos on this site are accompanied by Amnesty International commentary and background on the country being highlighted.

- ↑ See What is WITNESS?.

- ↑ See Important Update About the Hub.

- ↑ See Priscila Neri, [ http://hub.witness.org/en/HUB2Years 2 Years of the Hub – A Look Back].