Digital Newsmedia Group Two

The rise of the Internet and the ease of publishing online has led to the development of various online communications networks that have affected the way our society experiences the media more broadly. The idea of "citizen journalism," originally heralded as either the savior or the doom of more traditional news media, should be recognized as a complex, multi-faceted set of interactions between the "new" and "traditional" media. To be sure, some citizen journalism explicitly aims to fill in the gaps its participants perceive in traditional media coverage, by handling everything from coming up with the idea, to investigating it and discovering the facts, to analyzing the raw material, and writing and publishing the piece. But much of the true power of citizen journalism is in fact in the diversity of ways it manifests itself. By creating the platform through which traditional news media, the engaged online communities, and the public can easily interact and leverage the other's strong points, online media has the potential to dramatically improve our access to information.

None of this is to deny that its rise has underscored and probably exacerbated some serious issues with our media experience. The blurring of the lines between fact, opinion, news, entertainment, traditional media, participatory media, and various other traditional categories has resulted in a deluge of information difficult to differentiate. Whereas once Walter Cronkite was the most trusted man in America, a recent online poll voted a comedian the most trusted news anchor. This melding and meshing creates or emphasizes some serious questions about what the role of the media is or should be, whether the civic function of public information is being served, the way the media affects our relationships with each other, and even whether the search for capital-T Truth does or should remain a priority — and if so, how to encourage and foster it.

Background

As a relatively recent phenomenon, it would be intuitive for the history of participatory journalism to be reasonably easy to describe; it was within our lifetimes and several of the sources are still available. Nevertheless, a coherent storyline is difficult, if not impossible, to entangle, particularly when there is no broad consensus on precisely what we should label a particular phenomenon, or what the definition of a particular label should be.[1] For that reason, the following "history" is less a chronological account than an explanation of general trends.

A Short History of Online Participatory Journalism

Much of the debate over participatory journalism has actually been over its label and definition. Due to the exploratory nature of our inquiry, we do not want to limit its scope too much at the outset; on the other hand, a definition that encompasses the entire Internet is so broad as to make any inquiry essentially meaningless. We therefore adopt something like the following definition, accepting that it is definitely nebulous and probably overbroad. It involves the everyday citizen, or the "audience," somehow — as a new participant in an ongoing debate, as a new source of information, as a new synthesizer and analyzer of factual evidence, or as a new public voice in the marketplace of ideas. Even participation by commenting or reviewing existing articles is considered "Participatory Journalism." Nevertheless, the focus of our inquiry is on more substantive contributions: writing blog posts, submitting photos or videos, creation of a new "thread" - articles which further citizens can comment upon, or can be picked up by a top-down news media organization. In either all of these scenarios, the citizen is adding something new or providing a new angle on something else. We also focus on contributions focusing on "the news" or current events, as a way of attempting to cabin "journalism" into something at least somewhat manageable. This is essentially the same as the definition adopted by Dan Gillmore in WeMedia, of participatory journalism as "The act of a citizen, or group of citizens, playing an active role in the process of collecting, reporting, analyzing and disseminating news and information."[2]

Although there is no licensing for journalism, and no regulatory enforcement of particular ethical standards, traditional news sources each have codes of ethics that they expect reporters to follow.[3] Although the codes vary a little from place to place, they generally involve diligence in research, non-defamatory articles, accuracy in statements, and relevant news leading to the enhancement of knowledge among citizens. These standards are enforced in top-down news systems by very defined repercussions to the individual and the news agency he/she is a part of. With participatory journalism, however, no such top-down structure necessarily imposes such codes of conduct, and repercussions for violations are not as visceral, so journalistic standards may not always be met. However, it is rare for self-styled citizen journalists to work primarily from an individual blog; they seem to form communities, and once within those communities, norms may develop and repercussions exist in a way that may turn out to be self-enforcing in much the same way that more traditional journalist ethics are.[4]

Traditional media has become more reliant on citizen journalism as the advantages outweigh the drawbacks in many cases. Citizen Journalism has been said to make media more interactive by allowing comments and stories written by the the traditional readers of the articles. It allows quicker access to news and stories that would otherwise have never been reported appear on the front page. One of the most significant advantages is to localize news to a deeper level (e.g. live scores of high school sports games, etc...) by allowing real-time updates from the users. Oftentimes, user generated content spurs not only new topics - but leads to more news. For example:

- In December 2002, Trent Lott resigned as House Majority Leader after a blog commented on a racist remark he made

- People worked to identify the false nature of different 60 Minutes documents on President Bush

- Citizen Journalists identified the perpetrator in a Youtube video depicting an online prostitution scandal

Because of the greater breadth that the general populace has over breaking news stories and providing them for free in an equally as viral capacity as, for example, premium content on the New York Times - citizen journalism has become like non-profit journalism because of the absence of the need to subscribe to the top news sources for the same information.[5] Larry Atkins suggested that there should be a rating system in place for citizen contributors much like the eBay rating system and sessions should be held to teach journalistic standards to citizen journalists. This allows some validity in the users' comments, or at the very least - some recognition of the effort taken to verify all news sources that were used.[6]

Motivations of Citizen Journalists

Some citizen journalism is the leveraging or "bubbling up" of online media that individuals pursue for other reasons, without necessarily identifying that activity as "journalism," participatory or not. Online blogs, forums, and other communities have been active sites for debates, link-sharing, expressing outrage, and general life sharing and communication for as long as they have been available. With such a plethora of data available, it is not surprising that it has become a valuable source of information in its own right. But increasingly, people are also turning to much more explicit journalistic roles and identifying as "citizen journalists." The motivations that they have for doing so might provide some insight into the gaps that they are trying to fill the "mainstream media" and therefore also some ideas about what the most productive interactions between the two could be.

- One motivating factor behind more journalistic citizen journalism has been to provide local news coverage, either to fill in the gaps caused by closing or consolidation of local papers hit especially hard by the downturn of the newspaper industry more generally, or at level so local it may not have ever been able to sustain a local newspaper.[7] At least so far, citizen journalism does not seem to provide the functional equivalent to a local paper[8], but arguably having some local news is better than having none. Moreover, at least one study has recognized that they provide a valuable complement[9] and at least one account of local government officials feeling like they are being held responsible.[10]

- Globalization: On the opposite end of the spectrum, some citizen journalists join communities that are self-consciously global.[11] This is often to ensure a wide reach at both ends; that is, to facilitate access to information from all over the world, and make sure that it is distributed to news organizations around the world.[12]

- Finally, some are aimed at specific types of news, including product recalls, socially-responsible shopping, or technology policy.

- Some are motivated by a sense that the traditional media has failed to adhere to journalistic principles, and view citizen journalism as a way to bring them back. For example, the The Third Report states on its About page that many media outlets have "abandon[ed] the principals of journalism in favor of promoting an agenda."

- Some are more generous to traditional media, but note that the financial crisis prevents it from doing the kind of hard-hitting investigative journalism that it used to, and aims to use citizen journalism to fill the void.[13]

Although this is only a sample of the diverse motivations behind citizen journalism, they do seem to roughly fall into two categories: (1) to leverage the structure of the Internet to allow a broader diversity of news, and (2) to fill in the role that traditional journalists "used to" play and gave up either due to an agenda or financial difficulties.

Current Focus and Debate

The current debate about the role of participatory journalism and its relationship to traditional media is much more textured and subtle than the "Us Against Them: Will Citizen Journalism Replace Traditional Media?" dialogue that supposedly characterized the attitude of traditional and citizen journalists when it first arose in our consciousness in the early 2000s.[14] There is increased recognition of interactions between the two changing the nature of each, and increasing numbers of traditional journalists and their parent news organizations have embraced new forms of social interaction.[15]

Even recent contributions, however, have occasionally framed the debate as being for or against "citizen journalism," often primarily focusing on the word "journalism," and thus limiting the scope to individuals who self-consciously engage in their own independent journalism without interacting with more traditional news sources. Much of the "anti" citizen journalism arguments emphasize the training, level of analysis, and social commitment that is necessary to do true, "big-J" journalism.[16] All of these points are accurate, but hard-hitting investigative journalism has never been the exclusive focus of our media generally, nor even of journalism in particular.[17] Moreover, even the contemporary view of the role of journalism as serving the value of providing truth to the public is a relatively recent phenomenon.[18]

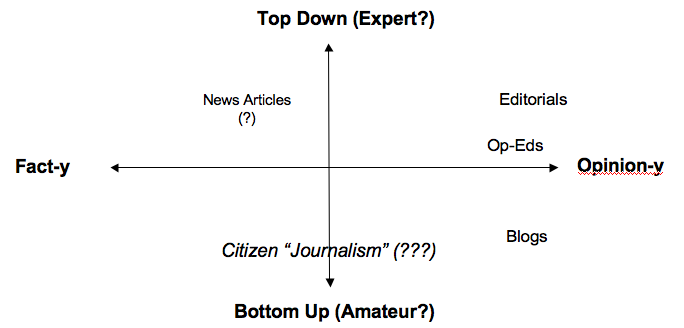

One strain of criticism of citizen journalism has been that it does not conform to the objectivity norm central to American journalism.[19] But the objectivity standard itself has been questioned; it is not the governing norm in Europe, for example.[20]. Moreover, the media has always encompassed a spectrum from "fact" to "opinion"; both traditional and participatory media fall at various points along the line from "fact" to "opinion." Even if citizen journalism is less "objective," a question on which we take no stand, it may still serve a valuable social function in contributing to the marketplace of ideas. Although "fact" information is extremely socially useful for ensuring that the public is informed and can properly execute civic duties, just because participatory media does not fall directly into that box does not necessarily make it useless.

Given the broader spectrum of the media, then, suggests that the underlying problem may be more of a concern over the label of citizen journalism than any inherent issue about objectivity.[21] If the label is the problem, its potential for harm lies in the extent to which people rely on it. But although the Internet has played an increased role as a news source, much of the content still seems to come from legacy news sources. As far as "objectivity" is concerned, communities of self-styled participatory media may develop norms / codes, either on own or imported from journalism, in order to increase legitimacy and provide value. [22]

Breakdown and a Rough Taxonomy

Perhaps because its proponents most visibly identify as "journalists" and therein raise the hackles of traditional, trained journalists, much of the normative debate has focused on those sites that allow individuals to act completely as "news gatherers": identifying a story that they think is newsworthy, going out into the world and collecting facts, analyzing those facts, and writing and publishing a story. But there are several stages in reporting a story, and participatory journalism also includes more complex interactions with traditional news media for various of these stages. We therefore provide the following table as a framework for thinking about various paradigms of participatory journalism and how they each try to leverage the relevant competencies of the entities that contribute to it.

| Idea | Newsworthy? | Fact Gathering | Analysis | Write | Publish | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Sometimes coming up with an idea and deciding whether newsworth is unnecessary, for example when reactively reporting something big that happened | Newspaper / TV | ||||

| Online Participatory | Internet (mostly) | |||||

This framework also provides value because it makes even more clear the ties between participatory journalism and Crowdsourcing. In crowdsourcing, someone provides a task and it goes out to the "crowd" to solve it. In the participatory journalism "special case," various types of tasks are allocated between more "top down" and more "bottom up" entities, allowing some insight into what types of things the various players do well. Even more than in crowdsourcing, the interactions between more participatory journalism and the traditional is self-conscious on both sides; each side is aware of the other and trying to take advantage of its strengths, trying to work with each other to come up with a model that will yield value for everyone involved. A legal analogy could be that traditional media, like judges, are better for questions of "analysis" — of figuring out where the value is in the story, and how to filter out the excess and present it in the most compelling way. The "crowd," on the other hand, like a jury, is more connected with the community, giving it much broader access to events as they happen.[23] But for mixed questions of law and fact, or (in the news) mixed questions of fact and analysis, the way that the two intertwine is more difficult. The following is a set of examples of participatory journalism and how it they shift and share responsibilities for different parts of the process. See also [The 11 Layers of Citizen Journalism, which also breaks down participatory journalism into different paradigms.

Examples

- Commenting on news articles; each participant can then "re-analyze" the facts and make own conclusions

- Spot.us

Allows the everyday citizen to submit article "tips"/"ideas" which are then distributed to partnering top-down news organizations. Upon interest from journalists there, the ideas are pitched and funded by citizens on Spot.Us. Represents a way that top-down and bottom-up journalism converge.

- CNN iReport (quite bottom-up, but meshes with top-down)

People can share stories or opinions based on prompts that they create or prompts that are provided. Based on the most votes and what reports are considered the best, CNN uses them on their external platforms like live news and their main news portal. A majority of the topics provided are not at the forefront of pressing events - current topics (12/19/10) include stories of "wintery weather" and "Travel Shots of Mexico."

- Knight Citizen News Network

"Self Help" Portal dedicated to helping citizen journalists start their own news service and reporting factually correct news to which people are reliant upon.

- Media Cloud (Beyond Publishing for Both Bottom-Up and Top-Down)

Allows users to track the flow of news data by visualizing the prevalence of different streams of information geographically to see the flow of media. It automatically builds an archive of news stories and collects data based on where they have spread.

- CBS EyeReport (Bottom-Up Publishing)

Colloquium of photos and videos that are supported by citizens. Based on most viewed and most discussed, the posts are ranked and displayed according to this popularity. There is no rating system, and the verification is in the fact that the information is only photos and videos.

- The Third Report (Bottom-Up Fact Gathering and Publishing)

Citizens become "The Third Man or Woman" by writing stories from a third-person perspective and not including opinion. They are compensated with up to 50% of the ad revenues generated by their article once on the website.

- AllVoices (Bottom-Up Sources)

Really the mother-ship of all citizen journalism websites. Incorporates individuals from across the world who are asked to report on current events in their location to get a truly international online news source. Discussions are encouraged, as are addendums to already posted articles.

- TechCrunch (Bottom-Up Fact Gathering and Publishing)

One of the most popular entrepreneurial, silicon-valley, news sources is a collection of insights from citizens in the area who are connected to those that are the subjects of the articles. Highly reliable in most people's minds.

- Center for Citizen Media (Bottom-Up Fact-Gathering and Learning)

Teaching citizen journalists the standards of journalism by making project-based atmospheres for people to work together and create a news story that is worthy of a top-down source. Other resources for participants in online media have taken different looks at the issue. For example, the Citizen Media Law Project seeks to provide legal assistance, information, and training to those involved in online media.

- National Examiner (Bottom-Up Publishing)

Considered more for entertainment than news, the national examiner focuses on local news built from the readers. It revolves heavily around entertainment and "gossip" related news.

See also:

- Sourcewatch List of Websites

- Sourcewatch wiki page on Citizen Journalism

- Six Journalism Startups

- E Pluribus Media

- J Lab

- Media Shift from PBS

A Closer Look at One Box

The bottom-up fact gathering box warrants closer scrutiny because it is one stage where people do not have to consciously self-identify as participants in the journalism process. Furthermore, it provides a fascinating overlap with Crowdsourcing because it goes both directions. Participation in this stage of the process may be responding to a prompt to feed a more traditional news source, or they may be tweeting about their daily lives and in the meantime providing valuable information that may turn out to be newsworthy to someone. Just going to the airport and tweeting to complain can be valuable "news" for someone deciding when to leave.

Fact Verification and News Creation

Because this stage of the process is one in which users do not have to self-identify as journalists, it is unlikely to be affected by any ethical norms or commitments made by citizen journalist communities. This especially causes a problem for verification, since there is no way to The Huffington Post has a clear description of various Standards of Citizen Journalism, which include identifying the author and all the sources that are used in the writing of a piece. These standards at least allow the public to draw its own conclusions about the reliability of sources used. But in many cases, the information provided by participatory media is most valuable when it cannot be checked because it is in a place that is difficult for journalists to access. Although a twitter feed provides substantial amounts of information, it can provide little value for verification purposes if it is primarily a catalog of daily life events punctuated by one newsworthy post out of being in the right place at the right time. Of course, in some cases there are little incentives for individuals to lie, which might affect the categories for which traditional news media actively solicit participatory contributions. (As of right now, CNN iReport Assignment Desk includes assignments on Wintry Weather, the Lunar Eclipse, High-mileage hybrids, and Mexico travel snapshots; hardly hard-hitting muckracking contributions.) But the issues that are really important for a functioning democracy are almost always those where someone has a vested interest on the other side, so fact checking may pose a bigger problem.

In Iran, Citizen Journalists are the sole sources that agencies like BBC and CNN use in order to provide coverage of the area. The restrictions on media have led to the significant rise of Citizen Journalists in the area, via, predominately, Twitter. BBC outright claimed that there was no way to verify the authenticity of anything that is said, but it is the only way. [24] The Presidential Elections, for example, have attracted significant attention on the social media platform.

Moreover, participatory journalism is not just about text; one of its core contributions is the use of still and video cameras on so many cell phones to capture events that occur suddenly, which the public may otherwise have no access to. Bringing devastating images from natural disasters, including Hurricane Katrina and the earthquake in Indonesia, it has also provided multiple videos of attested police brutality (for example, at the G20 summit). Because we tend to have a sense that something caught on video or in pictures is indisputable "fact," this seems to suggest that less verification is necessary. But even visual media can be manipulated; consider, for example, the ACORN Scandal. The Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now was "infiltrated" by James O'Keefe - a 25 year old filmmaker. He dressed as a pimp stereotype and shot scenes of himself, implying that he dressed the same way when he entered ACORN with a woman nicknamed "Kenya," and asked for housing and advice on continuing a prostitution service, implying ineptitude in detecting even such an "obvious" case. However, because the footage was shot from his perspective, it did not show that he actually dressed in normal business clothes, and the footage was largely edited to manipulate the way the conversation played out. The ACORN individuals readily helped, and the manipulated video was released on the internet by O'Keefe for the public to view. ACORN as a result had many employees fired and sued O'Keefe for defamation. See Investigation Video for ACORN

In this case, however, there seems to be no reason that traditional news could not have done more to verify the story before the damage was done — and in the end, the video was discredited.[25] But, perhaps caught up in the "rush to be first" explored more below, it was not until after the effects had been felt.

Taking a Step Back

Stepping away from the specifics of crowdsourced fact gathering and taking a big picture view, the problems of participatory journalism and online media merge into the problems of the traditional, mainstream media. In fact, the separation between the two is beginning to seem ever more illusory,[26] as the taxonomy of models for interactions between the two continues to expand, and the traditional media adapts in response and the online community continues to evolve. But there are real problems for whatever we want to call what is emerging out of the synthesis, of which a few are offered below.

Rush to be First

Although the concept of a "scoop" has long played a role in journalism, the ability of the public to be everywhere at once, beating out even those journalists first on the scene, and the proliferation of ways to publish descriptions, pictures, or even videos of a newsworthy event means citizens simply because of volume and access will probably often have the upper hand in breaking some kinds of news. Traditionally, top-down news sources competed to be the first by monitoring significant areas geographically, but such monitoring no longer guarantees that they will be first to hear about breaking news without also looking for tips in the blogosphere. Although the New York Times may criticize online blogs for publishing "half-baked" stories, most people recognize that "process journalism" is being practiced not only by blogs and new forms of media, but also by traditional news outlets.[27] Although characterizing the online media as the cause is certainly a disputable proposition (the advent of the 24 hour news cycle and increased commercialization of news has also been blamed[28]), the question remains as to whether this really is a problem. Some argue that "process journalism" should not necessarily be equated with "sloppy journalism," but instead as a more interactive and iterative mode of publishing.[29] But recognizing a role for process journalism does not mean that there is no value in "product journalism"; there is value in having access to a source that gives you "the news," traditionally understood, and in our market-driven media environment, such a product does not benefit from the expectation that the Internet will know about something as soon as it happens.

News and Entertainment

This is also not something that should be considered the sole responsibility of new media forms, but the blurring lines between news as information and news as entertainment may cause problems because a lot of the news that we need to know simply is not entertaining. Jay Rosen argues that "[t]he press has become the ghost of democracy in the media machine, and we need to keep it alive."[30]. But presumably mass media has moved in this way for a perfectly rational reason; it gets viewers, which bring advertisers, which provide money. Even if some of us continue to value and maintain a belief in the role of "The Press" in a legitimate democracy, its sustainability may fall into question. Currently, the trend seems to be toward non-profit investigative journalism centers[31] seems to be doing well (for example, ProPublica recently won a Pulitzer Prize for investigative journalism[32]) but it is still a little early to tell.

Manufacturing News

As discussed above, there is also a risk that bad actors may be able to influence and distort the public perception of the news, undermining the ability of the public to be informed. This risk may be exacerbated in the online context, where no corporate bureaucracy and editing process at least lessens the risk.[33] Moreover, since something published on the Internet usually cannot practically be taken back, any information that we as a society wish to keep off of it is at a much bigger risk of being leaked than was traditionally the case. The recent controversy over Wikileaks has brought this issue center stage, although there is no consensus on whether that information in particular might have been better left undisclosed.

Truth in Society

All of the issues discussed above involve the value of truth. A significant part of our cultural perception of the value of the press is in discovering the truth and bringing it to light, but our faith in the media — whether traditional or online — to effectuate that goal seems to have been shaken by a convergence of several factors, including the digital media and information overflow, the 24-hour news cycle and at least the perception (and probably the reality) of an increased commercialization of news. Academia values the search for truth as something that society ought to support even without a market for it; perhaps "capital-J" journalism should shift into something more like that model. Yet even if "the truth is out there," information overload may make it difficult to discover[34]. and even if we find it and read it, our constant context-shifting makes it difficult to properly determine whether something we remember came from a meticulously researched reliable news source or from an off-the-cuff blog post.[35] Moreover, the diversity of news sources available make it easy to seek out those that conform to your own particular ideology and world view and this "balkanization" may arguably lead to a lack of shared experiences and the ability to solve social problems.[36] Whether truth is possible and what role truth-seeking should have in society are big questions, but citizen journalism and the media more generally offer interesting insights into one facet of the issue.

Conclusion

Clearly, the debate stemming from Citizen Journalism extends beyond the conventional narrative. The phenomenon continues to grow as the Internet promotes the viral nature of user-generated content and facilitates interactions between participatory mechanisms and more traditional news. As the lines become blurred, the problems of participatory journalism do not remain specific to it, but have actually merged and either become, exacerbated, or highlighted problems with the media more generally.

- Citizen Journalism has led to several accounts of "news creation" rather than traditional "reporting" - Citizens, through videos (e.g. ACORN), create situations which they report as news

- Loss of Human Interaction - Reliance on blogs and social media for sources of information loses the traditional human interaction that allows the journalist to gauge accuracy, passion, and interest in the source in determining whether bias exists and how credible the source is

- Citizen Journalism Fact Verification - Oftentimes in areas where citizen journalism is the only way of obtaining information, it is impossible to verify the validity of what is said. This suggests that different levels of trust may be given to citizen journalism from different categories; although governments may have vested interests in manipulating social content that has to do with political realities and individuals may have biases and agendas that might lead them to present falsehood as fact, individuals tweeting about a long line at an airport or their cable being down have little incentive to lie.

Regardless of the problems that have arisen from participatory journalism, and even of the general problems with the media of which it sometimes provides an example, to the extent that the Internet has promoted public engagement with the news and fostered communities for discussing current events, it has also had a very positive impact. The jury may still be out on whether it can do all that its most ardent promoters have promised, but it already has provided much in the way of social value.

Notes

- ↑ See Stuart Allan, Histories of Citizen Journalism in Citizen Journalism: Global Perspectives.

- ↑ WeMedia, at 9.

- ↑ See, for example, the code for the New York Times.

- ↑ See, for example, this paper, which compares the "objectivity" norm of traditional American journalists with the Wikinews "neutral point of view" principle.

- ↑ See http://www.ojr.org/ojr/people/stverak/201003/1830/ Financial Crisis in Media.

- ↑ See http://www.ourblook.com/Citizen-Journalism/Larry-Atkins-on-Citizen-Journalism.html.

- ↑ See http://www.ourblook.com/Citizen-Journalism/Kirsten-Johnson-on-Citizen-Journalism.html for the opinion that citizen journalism may be useful for "hyperlocal" news. See also WeMedia, at 17–18 for the idea that online media more generally not only allows communication with faraway citizens but also fosters local relationships and strengthens local communitiies.

- ↑ See http://arstechnica.com/media/news/2010/07/citizen-journalism-not-making-up-for-loss-of-local-newspapers.ars

- ↑ See http://www.digitaljournal.com/article/292589

- ↑ http://www.pbs.org/mediashift/2010/01/local-bloggers-step-up-to-watchdog-local-government014.html

- ↑ See, for example, http://www.allvoices.com/about.

- ↑ See, for example, http://www.demotix.com/welcome; http://visionon.tv/mission.

- ↑ For comments to this effect, see http://www.ojr.org/ojr/people/stverak/201003/1830/; http://www.ourblook.com/The-Media/The-Rise-of-the-Citizen-Journalism.html; http://citmedia.org/blog/2006/01/31/qa-about-the-center/.

- ↑ See, e.g., http://www.editorsweblog.org/analysis/2005/12/from_citizen_journalism_myth_to_citizen.php; http://www.hypergene.net/blog/weblog.php?id=P327!. But even this angle of the narrative may be oversimplified; consider this article, published in 2003.

- ↑ See, e.g., http://blogs.reuters.com/fulldisclosure/2009/01/30/twittering-away-standards-or-tweeting-the-future-of-journalism/.

- ↑ http://blog.digidave.org/2009/11/dont-save-journalism-save-honest-communication

- ↑ http://www.fairreporters.org/portal/fairnew/docs/IJ_Manuals/Chapter_1.pdf

- ↑ See The Journalism of Outrage: Investigative Reporting and Agenda Building in America.

- ↑ See http://www.prospect.org/cs/articles?article=questioning_journalistic_objectivity

- ↑ See id.; http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/pda/2010/nov/01/objectivity-real-citizen-journalism. For more on the history of the objectivity norm, see http://www.une.edu.py/maestriacs/schudson_the_objectiviy_norm_in_american_journalism_journalism_2.2.pdf.

- ↑ Professor David Weaver has suggested "citizen communication".

- ↑ See, for example, Wikinews and its "neutral point of view."

- ↑ See this post for a critique of citizen journalism as "See, snap, post" without providing any depth.

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8176957.stm.

- ↑ See http://mediamatters.org/columns/201003020001.

- ↑ An illustrative question often asked in the discussion is "Who is a journalist and does it matter?" See Dan Gillmore's post as an example.

- ↑ See http://www.j-source.ca/english_new/detail.php?id=5173; http://blog.journalistics.com/2009/process_journalism_and_it_twitter_enabler/ traditional news outlets.

- ↑ See Thomas E. Patterson, Bad News, Bad Governance 546 Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 97, 103 (Jul., 1996).]

- ↑ See, e.g., http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jeff-jarvis/product-v-process-journal_b_212325.html.

- ↑ http://pressthink.org/about/

- ↑ http://www.editorsweblog.org/analysis/2009/02/propublica_could_the_non-profit_model_be.php

- ↑ http://www.propublica.org/about/

- ↑ See http://www.ourblook.com/Citizen-Journalism/Richard-Roher-on-Citizen-Journalism.html for this view.

- ↑ http://articles.cnn.com/2010-02-03/tech/content.overload_1_content-rss-algorithm?_s=PM:TECH

- ↑ http://gulfnews.com/life-style/general/it-s-tmi-age-of-information-overload-1.723336

- ↑ See Cass Sunstein, Republic.com. However, some initial empirical research indicates that this has not yet occurred in political discourse. See Paul DiMaggio and Kyoko Sato, Does the Internet Balkanize Political Attention?: A Test of the Sunstein Thesis.