Existing Services: Difference between revisions

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

===Mapping the Competition=== | ===Mapping the Competition=== | ||

====Second Quadrant==== | |||

So what organizations currently fill this space? The second quadrant, in the upper right of the chart, includes for-profit, multinational organizations that host user-generated content. YouTube and Facebook are two popular organizations that fall directly into this quadrant.<ref>Other organizations might include Flickr, Vimeo, Veoh, and Metacafe.</ref> Anyone with access can upload content on YouTube and publish it to the world, as long as it does not contain pornography or graphic violence.<ref>See [http://www.youtube.com/t/community_guidelines?gl=GB&hl=en-GB YouTube Community Guidelines].</ref> Although YouTube is well-suited to host and disseminate large amounts of human rights media, it is still subject to outside pressures. Governments can force YouTube to limit the availability of certain content by threatening to block the site in their country. In 2008, for example, YouTube removed a controversial video critical of Islam in order to end Pakistan’s ban of the site.<ref>See Greg Sandoval, [http://www.youtube.com/t/community_guidelines?gl=GB&hl=en-GB Pakiston Welcomes Back YouTube], CNet (Feb. 26, 2008).</ref> Actions such as these demonstrate that sites like YouTube have a serious misalignment of interests and are not perfectly suitable to serve as publishers of human rights media. | So what organizations currently fill this space? The second quadrant, in the upper right of the chart, includes for-profit, multinational organizations that host user-generated content. YouTube and Facebook are two popular organizations that fall directly into this quadrant.<ref>Other organizations might include Flickr, Vimeo, Veoh, and Metacafe.</ref> Anyone with access can upload content on YouTube and publish it to the world, as long as it does not contain pornography or graphic violence.<ref>See [http://www.youtube.com/t/community_guidelines?gl=GB&hl=en-GB YouTube Community Guidelines].</ref> Although YouTube is well-suited to host and disseminate large amounts of human rights media, it is still subject to outside pressures. Governments can force YouTube to limit the availability of certain content by threatening to block the site in their country. In 2008, for example, YouTube removed a controversial video critical of Islam in order to end Pakistan’s ban of the site.<ref>See Greg Sandoval, [http://www.youtube.com/t/community_guidelines?gl=GB&hl=en-GB Pakiston Welcomes Back YouTube], CNet (Feb. 26, 2008).</ref> Actions such as these demonstrate that sites like YouTube have a serious misalignment of interests and are not perfectly suitable to serve as publishers of human rights media. | ||

====Third Quadrant==== | |||

Actors in the third quadrant also do not provide an ideal platform for promoting human rights media. This space is dominated by traditional news organizations such as the New York Times, CNN, Reuters, and the Associated Press. Although these organizations are subject to many of the same financial pressures as quadrant one organizations, they are generally less willing to cater to oppressive governments. The real problem with using these organizations to promote human rights media, however, is the hierarchical structure they use to select content. Many organizations lack a system by which users can send in their content for publication, forcing them use services like YouTube. Even if an organization does accept user-generated content, editors ultimately decide which information is worthy of the limited time or space they have to present the news. When these large news organizations cover human rights abuses, they often focus on countries where Western powers have some involvement.<ref> For example, one study of the New York Times found that "[a]ttention to abuses occurs primarily in countries that were strategically instrumental during the cold war and in countries where there is clear U.S. involvement." See Caliendo et al., [http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/harvard_international_journal_of_press_politics/v004/4.4caliendo.html All the News That's Fit to Print? New York Times Coverage of Human-Rights Violations].</ref> As a result, important human rights media may not be chosen for publication. | Actors in the third quadrant also do not provide an ideal platform for promoting human rights media. This space is dominated by traditional news organizations such as the New York Times, CNN, Reuters, and the Associated Press. Although these organizations are subject to many of the same financial pressures as quadrant one organizations, they are generally less willing to cater to oppressive governments. The real problem with using these organizations to promote human rights media, however, is the hierarchical structure they use to select content. Many organizations lack a system by which users can send in their content for publication, forcing them use services like YouTube. Even if an organization does accept user-generated content, editors ultimately decide which information is worthy of the limited time or space they have to present the news. When these large news organizations cover human rights abuses, they often focus on countries where Western powers have some involvement.<ref> For example, one study of the New York Times found that "[a]ttention to abuses occurs primarily in countries that were strategically instrumental during the cold war and in countries where there is clear U.S. involvement." See Caliendo et al., [http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/harvard_international_journal_of_press_politics/v004/4.4caliendo.html All the News That's Fit to Print? New York Times Coverage of Human-Rights Violations].</ref> As a result, important human rights media may not be chosen for publication. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 21:32, 2 February 2011

Human rights videos are currently disseminated through a variety of traditional and new media outlets. While these services have allowed many important human rights videos to reach an unprecedented audience, they are currently inadequate in two ways. First, none of the existing solutions have the proper alignment of incentives to support human rights media. Second, none of the services provide both secure anonymous uploading mechanisms and tools to ensure the anonymity of the videos’ subjects.

Alignment of Incentives

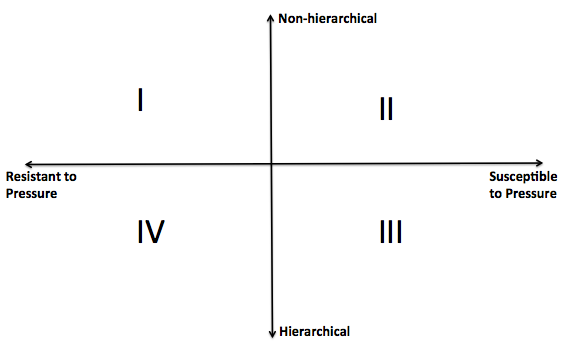

In order to explain why none of the current solutions have adequately solved the problems facing human rights media, it is helpful to plot these solutions using two important variables. First, the horizontal axis measures how susceptible these organizations are to government and financial pressures. Organizations that are more susceptible to pressure can be found on the right-hand side of the chart, while organizations that are resistant to these pressures reside on the left-hand side. Second, the vertical axis looks at the extent to which an organization filters the content it publishes. At the top, non-hierarchical organizations generally take a hands-off approach to the content available on their websites. Hierarchical organizations, on the other hand, exercise great control in the selection and promotion of human rights media. The basic chart is presented below.

Mapping the Competition

Second Quadrant

So what organizations currently fill this space? The second quadrant, in the upper right of the chart, includes for-profit, multinational organizations that host user-generated content. YouTube and Facebook are two popular organizations that fall directly into this quadrant.[1] Anyone with access can upload content on YouTube and publish it to the world, as long as it does not contain pornography or graphic violence.[2] Although YouTube is well-suited to host and disseminate large amounts of human rights media, it is still subject to outside pressures. Governments can force YouTube to limit the availability of certain content by threatening to block the site in their country. In 2008, for example, YouTube removed a controversial video critical of Islam in order to end Pakistan’s ban of the site.[3] Actions such as these demonstrate that sites like YouTube have a serious misalignment of interests and are not perfectly suitable to serve as publishers of human rights media.

Third Quadrant

Actors in the third quadrant also do not provide an ideal platform for promoting human rights media. This space is dominated by traditional news organizations such as the New York Times, CNN, Reuters, and the Associated Press. Although these organizations are subject to many of the same financial pressures as quadrant one organizations, they are generally less willing to cater to oppressive governments. The real problem with using these organizations to promote human rights media, however, is the hierarchical structure they use to select content. Many organizations lack a system by which users can send in their content for publication, forcing them use services like YouTube. Even if an organization does accept user-generated content, editors ultimately decide which information is worthy of the limited time or space they have to present the news. When these large news organizations cover human rights abuses, they often focus on countries where Western powers have some involvement.[4] As a result, important human rights media may not be chosen for publication.

References

- ↑ Other organizations might include Flickr, Vimeo, Veoh, and Metacafe.

- ↑ See YouTube Community Guidelines.

- ↑ See Greg Sandoval, Pakiston Welcomes Back YouTube, CNet (Feb. 26, 2008).

- ↑ For example, one study of the New York Times found that "[a]ttention to abuses occurs primarily in countries that were strategically instrumental during the cold war and in countries where there is clear U.S. involvement." See Caliendo et al., All the News That's Fit to Print? New York Times Coverage of Human-Rights Violations.