Cybersecurity Project: Difference between revisions

explanation of Tower Defense |

|||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

[[Image:Tower Defense Diagram.png]] | [[Image:Tower Defense Diagram.png]] | ||

Each of of these different conceptions would have largely the same structure, shown in the diagram above: An infected computer signs in to a website such as Facebook or eBay. At this point, both the website and the ISP can tell that the computer may be infected.<ref> ISPs and websites can tell when a computer has a port open, waiting for commands that is not related to where the user is browsing</ref> Rather than inform the user directly and risk alienating his/her business, the ISP or website informs the Tower Defense program that it is connected to an infected computer. The Tower Defense program can then either ( | Tower Defense can be conceived in three ways: (1) as an "Amber Alert" for internet threats, (2) as a kind of invasive surgical procedure to remove malware, or (3) as an independent community of 'Good Cyber Samaritans.' | ||

Each of of these different conceptions would have largely the same structure, shown in the diagram above: An infected computer signs in to a website such as Facebook or eBay. At this point, both the website and the ISP can tell that the computer may be infected.<ref> ISPs and websites can tell when a computer has a port open, waiting for commands that is not related to where the user is browsing</ref> Rather than inform the user directly and risk alienating his/her business, the ISP or website informs the Tower Defense program that it is connected to an infected computer. The Tower Defense program can then either (1) inform the user that his/her computer may be infected, (2) connect to the infected computer through the website or ISP to quarantine or cure the infected computer ''with'' the users knowledge and permission, or (3) connect to the infected computer through the website or ISP to quarantine or cure the infected computer ''without'' the users knowledge and permission. | |||

Hopefully, the Tower Defense program can act as a kind of Mutual Aid Treaty for the Internet, allowing websites and ISPs to (perhaps anonymously) combine their information about possible online threats so that all can be safer (This, however, may create free rider problems of its own). | |||

==="Amber Alert" For The Internet=== | ==="Amber Alert" For The Internet=== | ||

What if a coalition of leading Internet sites were willing to share certain information about security threats with a third party organization (like [http://stopbadware.org/home/index StopBadware]), and the third-party would vet the information and then issue certain "Amber Alerts" that all the sites would be willing to publicize in some way? When there's a particularly egregious security hole in an [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_Explorer_6 old browser], for instance, if all the leading websites actively encouraged its users to patch it, that has the potential to do a lot of good. Google has just recently begun to do this by [http://googleenterprise.blogspot.com/2010/01/modern-browsers-for-modern-applications.html phasing out support] for older browsers with security issues. | |||

If such actions and recommendations are filtered through a reliable third-party, perhaps the companies who are reluctant to contribute their information won't be threatened by the embarrassment of having an "Amber Alert" put out, and perhaps actions like the ones Google has begun to take can become more effective. Sure, there would be negative consequences for a company, just as a company who undertakes a product recall generates bad publicity. But ultimate the hope is that companies will realize the net positive value of this transaction, and that consumers will look kindly on companies promoting a new level of honesty and transparency. | |||

===Cyber Surgery=== | |||

Just as it is impossible to eliminate all security threats by informing internet users of security problems in the abstract, it may also be impossible to eliminate these threats by simply alerting users that their computer may be infected. Since these users apathy or unwillingness to take steps towards security are the original source of the problem, an "Amber Alert" system may be insufficient to substantially eliminating the problem. | |||

Under a Cyber Surgery model, a website or ISP could inform the Tower Defense program running passively on an educated users computer that an infected computer is logged into the site/ISP. The Tower Defense program could then connect to the infected users computer via Mesh Networking through the ISP or website and quarantine or remove the malware on the infected computer. Because this model is designed to overcome user inertia or apathy, this quarantining or removal of malware would have to occur without the infected computer's user's knowledge or consent. | |||

There are a number of new dangers to this approach. First, hackers may try to subvert this software to quarantine or delete good files on other computers rather than malware and viruses. Hopefully a Tower Defense program would preclude this possibility by running passively on a users computer and would not present any opportunity for the user to interact with or control the program. Next, running software or altering the state of another computer without permission may not be ethical or legal. The legal ramifications could be removed through legislation if Congress or the relevant governing body could be convinced that this is a good use of the technology. The ethical dilemma is trickier. Finally, creating a centralized list of infected computers could be very dangerous if hackers were to get ahold of it. This may be mitigated by not maintaining a centralized list, but instead only having the websites or ISPs inform individual Tower Defense programs running on individual computers when a virus or piece of malware is nearby, thus diluting and dispersing the risk. Still, even on a single computer, the few pieces of information about infected computers nearby could cause a problem in the hands of hackers. | |||

===Good Cyber-Samaritans=== | ===Good Cyber-Samaritans=== | ||

Finally, if legal or technological barriers preclude the creation of a Tower Defense program operating as an Amber Alert or Cyber Surgeon, perhaps there could be a network of young people who think security is important and who don't mind hanging around their local library for a few hours helping people update software and patching security holes. Companies and ISPs could upload possible security issues to a Stop Badware-like website where educated and interested users could go, and propose solutions which the companies could then implement. Essentially, this is crowdsourcing cybersecurity patches. This solution becomes ever-more feasible as a greater proportion of users switches to laptop computers and as projects showing that people are willing to assist strangers for the sheer fun and satisfaction of the experience - from building an [http://www.wikipedia.org encyclopedia] to giving them a [http://www.couchsurfing.org couch to crash on] for free - flourish. Relying on people's good natures could be a new way to make progress on this problem. | |||

This proposal has its own challenges. Many companies still believe in security through obscurity and might not be inclined to share their security breaches with a publicly accessible website. Also, there would have to be a process for vetting the security fixes to make sure that they both work and don't include new trojans. Also, this kind of higher-level skilled work is not as readily appropriate to crowdsourcing as things like the tasks commonly associated with Mechanical Turk. | |||

==Distress Password== | ==Distress Password== | ||

| Line 144: | Line 155: | ||

I'm in! | I'm in! | ||

= | =Footnotes= | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 00:14, 31 January 2010

Topic Owners: Mike, Jason, Ramesh, and Sheel

Saying that cybersecurity is a "difficult problem" is like saying that reversing global warming is a difficult problem: it's true, but it doesn't quite capture how devilishly complicated and multifaceted the problem really is. There's no single reason why creating a more secure global network is so difficult; it in part has to do with the radically-distributed architecture of the Net, in part with some deep flaws computer software for both consumers and businesses, and in part from the network's sheer size and importance to our daily lives. (For more on this, see the nice Cybersecurity backgrounder.)

Our group approached the problem not with the goal of inventing a panacea that would make all credit card transactions magically secure and make it impossible for hackers to compromise Gmail's security. Instead, we wanted to offer suggestions with minimal implementation headaches and maximal benefit to users, from novices to experts.

The final "product" of our month-long thinking on this issue begins with a reasonably short video overview of our ideas here, (or see below), explains some of the details of our proposal, and also has an alpha-release Firefox plugin that you can download and try out (thanks to Elance for making the plugin possible, by the way).

Overview

We discussed this topic at length in an in-class presentation on January 19. This 9-minute video summarizes and extends the presentation we gave that day. The details on this page elaborate on the proposals mentioned in the video.

Guiding Principles

Before turning to the specific proposals we've made to improve cybersecurity, it's helpful to discuss some of the guiding principles that have informed our work. We applaud the government's attempts to improve cybersecurity, but don't believe that a top-down, regulatory or legislative solution is a panacea.

Empowering Users

Cybersecurity is a huge, complicated problem, conceivably including everything from keeping the electrical grid from going down to garden-variety phishing spam. We consciously left the SCADA problem to those in government and industry, and focused on problems that face ordinary users.

We suggest tools that rely both on the power users who have contributed much to the internet's development as well as the ordinary users who are the overwhelming share of people online today. Bottom-up solutions seem improbable when they begin; Wikipedia and Firefox, to take just two examples, were thought to face extremely long odds. We believe that giving users the tools they need to take control of their own security can improve users' experiences on the net, as well as convincing major market players to adopt similar solutions that will help everyone, including those users who haven't taken affirmative steps to protect their security.

Nudging Users

The mind sciences and behavioral economics have demonstrated the tinkering with default settings and gently nudging people in a direction can cause dramatic changes in behavior. We apply that insight to cybersecurity. If it's a little harder to reuse or create weak passwords, or a little easier to find out what malware has infected your computer, security may greatly improve.

Code is Law

Lawrence Lessig's 1999 insight that code is law is still crucial to understand cybersecurity more than ten years later. Most fundamentally, the major browsers and websites can improve (or worsen) security for users, perhaps much more than the government can. Key browsers and websites, by coding our proposals or other security fixes, can make a major impact on security.

No big thing, many little things

Finally, we consider ourselves foxes, rather than hedgehogs, and believe that there's no one big thing, or top-down solution, by the government or the private sector, that could solve the cybersecurity problem overnight. Cybersecurity has so many dimensions that it must be improved on all levels, by the government, by industry, by non-profits, and by users. Even if the net suddenly became more secure, in a few months or years new vulnerabilities would be exposed and take the place of the old. As long as the Net remains open, cybersecurity will be a never-ending arms race, and we believe that empowering users, nudging them to better security practices, and remembering that code can be law can give the good guys the upper hand.

Specific Proposals

Public Service Announcement

We created a Public Service Announcement for generating public awareness for the cybersecurity problem, and showed it in class on January 19. It's online here but is password-protected. Please email us if you were in the class and would like the password.

The upshot of the video is that we don't think a direct public awareness campaign will be very effective. We believe it would be more productive to nudge users and change their behavior by altering the way browsers and websites work, not by scolding people in 30-second TV ads.

SafeWord

What is SafeWord?

SafeWord is a real, working FireFox plugin designed to nudge users into keeping safer and more unique passwords, though it's too unstable and unrefined to be considered anything but alpha software at this point. It's available for download here. To install, save that file to your disk, select File --> Open in Firefox 3.5 or above, and install it. You will need to restart Firefox before it takes effect. Thanks to Elance for helping with the coding on very short notice.

We have created a video demonstration of one of the key features of SafeWord here.

What Are The Goals of SafeWord?

SafeWord begins with a simple proposition: online passwords should be both strong and also different across different sites, and your browser should help you achieve that goal. Studies continue to show that most people use very simple passwords; see, for instance, this New York Times article that gets right to the point. "If your password is 123456," reads the headline, "just make it HackMe." Moreover, most users also fall into the "dirty habit" of using the same password across multiple online accounts, which can lead to a disaster if only one of the accounts is able to be compromised. An extremely detailed analysis of a 2009 attack that used this principle to compromise many online accounts of Twitter employee is here.

More on The Unique Password Feature

A Scary Story, and A Word About Annoyance

Even readers who are all for stronger password security in general may nonetheless be skeptical of what can happen to "regular people" who can't be bothered to remember so many passwords. But here's a very scary story - which is taken directly from the Twitter attack analysis cited above - of what can happen if users employ the same password at multiple important sites:

- HC [the hacker's alias] accessed Gmail for a Twitter employee by using the password recovery feature that sends a reset link to a secondary email. In this case the secondary email was an expired Hotmail account, he simply registered it, clicked the link and reset the password, giving him control of the Gmail account.

- HC then read emails to guess what the original Gmail password was successfully and reset the password so the Twitter employee would not notice the account had changed.

- HC then used the same password to access the employeeâs Twitter email on Google Apps, getting access to a gold mine of sensitive company information from emails and, particularly, email attachments.

- HC then used this information along with additional password guesses and resets to take control of other Twitter employees' personal and work emails.

- HC then used the same username/password combinations and password reset features to access AT&T, MobileMe, Amazon and iTunes, among other services. A security hole in iTunes gave HC access to full credit card information in clear text. HC now also had control of Twitterâs domain names at GoDaddy.

- Even at this point, Twitter had absolutely no idea they had been compromised.

That's the danger, and it ain't pretty.

On the other hand, as SafeWord users, we admit that the aspect of the program that requires you to use a different password for each new login is, well, pretty damn annoying. Complying with its demands to keep generating unique passwords might even require some old-fashioned tricks, like the creation of a heuristic for generating memorable but unique passwords or keeping a card in your wallet to keep track of your various logins (and maybe even separating out parts of that list or keeping it encoded somehow). Still, we think that the cost/benefit analysis weighs in favor of life being just a little more annoying in this area, because as our scary story illustrates, there are lots of points-of-entry to our various accounts, and lots of random people out there who would love to hack those accounts for financial gain or to get their kicks.

Why Do It This Way?

There are other solutions out there that automatically generate secure, unique passwords for each site you visit; LastPass is a particularly nifty one. But they all share several key points of failure: they rely on a master password, and they store your passwords in the cloud. Relying on a master password is particularly problematic, because a compromise of that password can lead to the same disastrous chain of events that we are trying to prevent. The only way to truly reduce the risk of this type of threat is to decentralize everything. And if that takes encouraging people to work a little harder, we at least want to make people aware that this just might be worth the hassle. Similarly, there are problems with storing passwords in the cloud, including intruder problems and problems if the company goes out of business or the cloud becomes inaccessible.

Extension v. Built-in Feature

Initially, we hoped to build this extension to make a pitch to Mozilla that they should think about building this kind of functionality into the browser. But as we have used a now-working copy of SafeWord in our browsers - admittedly, it's an alpha copy that's not even close to ready for prime-time - at least two of us (i.e. jharrow and rnagarajan) see that it's just too intrusive for mainstream users. If the average, busy user gets a pop-up every time he comes across a new website and tries to use an old password, he will get angry at the browser. If this happens a few times, he will probably switch from Firefox to another browser. So right now, the idea works best as an extension for people who really believe in password security and want a little nudge when they are thinking of giving in to the instinct to just use the password they used last time. But if SafeWord could work only with websites that store important personal information -- email providers, financial institutions, retailers with your credit card information -- and ignore the local newspaper's website, perhaps the balance between security and frustration would be a little closer to the former.

More on the Stronger Password Feature

On the other hand, the idea of adding a feature that helps users create more secure passwords - even if they are reused across multiple accounts - is a simple fix that should enhance the browsing experience for most users.

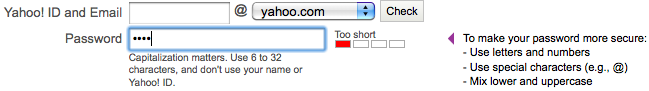

Increasingly, many websites are giving users some guidelines on password security. For instance, Yahoo!'s sign-up page looks like this:

We think that's great. But not all sites have that feature. For instance, you get no visual feedback if you sign-up for an Amazon account with a weak password:

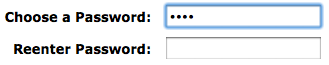

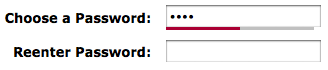

Your browser can change this state-of-affairs easily. Here's the new view, with a SafeWord bar underneath the password field reminding you that your password is weak:

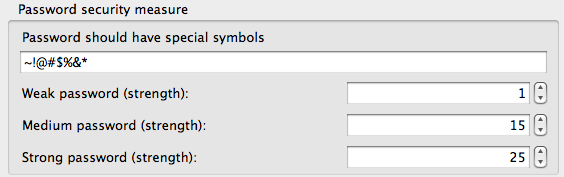

SafeWord even lets you customize the password strength options:

We think something like this really could be built into the browser, and would both add to the user experience and increase security.

Tower Defense

Tower Defense is a metaphor for a particular strategy of addressing cybersecurity threats.[1] Certain threats, like Distributed Denial-of-Service attacks or malware like viruses and worms take advantage of the free rider problems associated with security on the internet -- ignoring secure computers and instead leveraging the still significant number of insecure computers to wreak havoc online. No matter how much understanding a public awareness campaign might generate, some percentage of users will remain unaware and their computers will remain susceptible to botnets and malware. Companies such as eBay, Amazon, and Google, which might be in a position to alert users when their computers are infected, don't want to alert their users for fear of driving away business. Tower Defense is a strategy to address this issue by empowering educated users to help out their less computer-savvy friends and neighbors with computer security problems just...because.

Since the initial conception of this idea, there have been some promising signs that organizations are starting to take steps in this direction.

How Tower Defense Works

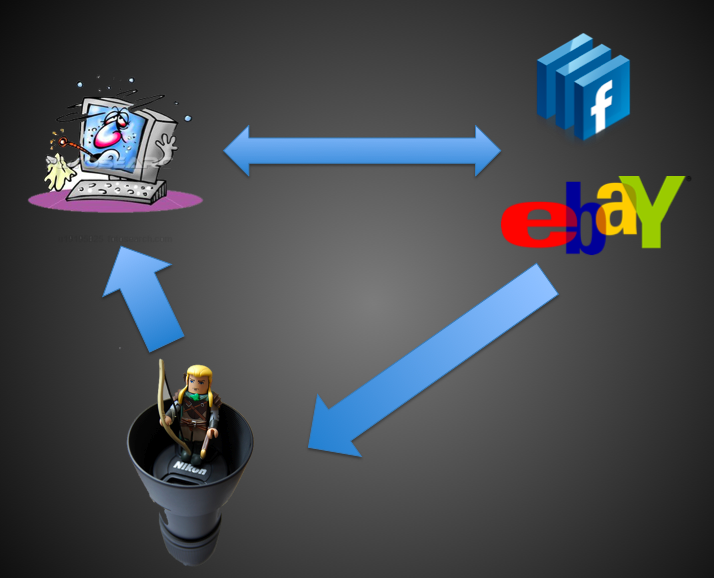

Tower Defense can be conceived in three ways: (1) as an "Amber Alert" for internet threats, (2) as a kind of invasive surgical procedure to remove malware, or (3) as an independent community of 'Good Cyber Samaritans.'

Each of of these different conceptions would have largely the same structure, shown in the diagram above: An infected computer signs in to a website such as Facebook or eBay. At this point, both the website and the ISP can tell that the computer may be infected.[2] Rather than inform the user directly and risk alienating his/her business, the ISP or website informs the Tower Defense program that it is connected to an infected computer. The Tower Defense program can then either (1) inform the user that his/her computer may be infected, (2) connect to the infected computer through the website or ISP to quarantine or cure the infected computer with the users knowledge and permission, or (3) connect to the infected computer through the website or ISP to quarantine or cure the infected computer without the users knowledge and permission.

Hopefully, the Tower Defense program can act as a kind of Mutual Aid Treaty for the Internet, allowing websites and ISPs to (perhaps anonymously) combine their information about possible online threats so that all can be safer (This, however, may create free rider problems of its own).

"Amber Alert" For The Internet

What if a coalition of leading Internet sites were willing to share certain information about security threats with a third party organization (like StopBadware), and the third-party would vet the information and then issue certain "Amber Alerts" that all the sites would be willing to publicize in some way? When there's a particularly egregious security hole in an old browser, for instance, if all the leading websites actively encouraged its users to patch it, that has the potential to do a lot of good. Google has just recently begun to do this by phasing out support for older browsers with security issues.

If such actions and recommendations are filtered through a reliable third-party, perhaps the companies who are reluctant to contribute their information won't be threatened by the embarrassment of having an "Amber Alert" put out, and perhaps actions like the ones Google has begun to take can become more effective. Sure, there would be negative consequences for a company, just as a company who undertakes a product recall generates bad publicity. But ultimate the hope is that companies will realize the net positive value of this transaction, and that consumers will look kindly on companies promoting a new level of honesty and transparency.

Cyber Surgery

Just as it is impossible to eliminate all security threats by informing internet users of security problems in the abstract, it may also be impossible to eliminate these threats by simply alerting users that their computer may be infected. Since these users apathy or unwillingness to take steps towards security are the original source of the problem, an "Amber Alert" system may be insufficient to substantially eliminating the problem.

Under a Cyber Surgery model, a website or ISP could inform the Tower Defense program running passively on an educated users computer that an infected computer is logged into the site/ISP. The Tower Defense program could then connect to the infected users computer via Mesh Networking through the ISP or website and quarantine or remove the malware on the infected computer. Because this model is designed to overcome user inertia or apathy, this quarantining or removal of malware would have to occur without the infected computer's user's knowledge or consent.

There are a number of new dangers to this approach. First, hackers may try to subvert this software to quarantine or delete good files on other computers rather than malware and viruses. Hopefully a Tower Defense program would preclude this possibility by running passively on a users computer and would not present any opportunity for the user to interact with or control the program. Next, running software or altering the state of another computer without permission may not be ethical or legal. The legal ramifications could be removed through legislation if Congress or the relevant governing body could be convinced that this is a good use of the technology. The ethical dilemma is trickier. Finally, creating a centralized list of infected computers could be very dangerous if hackers were to get ahold of it. This may be mitigated by not maintaining a centralized list, but instead only having the websites or ISPs inform individual Tower Defense programs running on individual computers when a virus or piece of malware is nearby, thus diluting and dispersing the risk. Still, even on a single computer, the few pieces of information about infected computers nearby could cause a problem in the hands of hackers.

Good Cyber-Samaritans

Finally, if legal or technological barriers preclude the creation of a Tower Defense program operating as an Amber Alert or Cyber Surgeon, perhaps there could be a network of young people who think security is important and who don't mind hanging around their local library for a few hours helping people update software and patching security holes. Companies and ISPs could upload possible security issues to a Stop Badware-like website where educated and interested users could go, and propose solutions which the companies could then implement. Essentially, this is crowdsourcing cybersecurity patches. This solution becomes ever-more feasible as a greater proportion of users switches to laptop computers and as projects showing that people are willing to assist strangers for the sheer fun and satisfaction of the experience - from building an encyclopedia to giving them a couch to crash on for free - flourish. Relying on people's good natures could be a new way to make progress on this problem.

This proposal has its own challenges. Many companies still believe in security through obscurity and might not be inclined to share their security breaches with a publicly accessible website. Also, there would have to be a process for vetting the security fixes to make sure that they both work and don't include new trojans. Also, this kind of higher-level skilled work is not as readily appropriate to crowdsourcing as things like the tasks commonly associated with Mechanical Turk.

Distress Password

This was an idea originally discussed at the Liberation Technologies Seminar in the Fall of 2009 and was expanded upon by the team. Imagine you have confidential information in your email (as most of us do) and you are captured by a hostile terrorist organization. They demand your Facebook and Gmail passwords. As of now, we only have one password: the real one. But, what if we had a distress password that, if entered could:

a) delete the account, or say it was 'temporarily suspended' b) show the email account, but only emails that you had marked as safe (or, in other words, only those which you hadn't filtered as 'private') c) require to you call customer service due to 'unauthorized activity'

This could easily be implemented by any email service provider.

Password Picture

The purpose of the password picture idea is to prevent against keystroke detectors on public computers gaining access to passwords. This dual authentication system would require the typical typed-in password, as well as the user to select, from a series of pictures, the picture or pictures that match the category given at the time of signup (perhaps updated every 3 months). It would work like this:

Say, when creating an account on Gmail, Gmail gave me the category 'tree' and 'car'. Here is what would happen when I went to log in:

1) I'd have to type my password 2) Then, from a series of 20 pictures, I would have to pick the one that is a tree. 3) Then, from a series of 20 pictures, I would have to pick the one that is a car.

I'm in!

Footnotes

- ↑ Tower Defense is a genre of computer game in which the player places 'towers' alongside a path that goes across the screen. Enemies cross the screen along the path and the towers shoot at the enemies, hopefully eliminating them before they reach the other side of the screen. The Player does not have control over the towers' operation, only their placement. Similarly, Tower Defense as a cybersecurity strategy would hopefully place concerned users strategically throughout IP addresses on the internet such that they could passively identify and correct viruses and botnets passing through nearby computers.

- ↑ ISPs and websites can tell when a computer has a port open, waiting for commands that is not related to where the user is browsing