Module 2: The International Framework

By Petroula Vantsiouri and William Fisher

Learning objective

This module discusses international copyright law. It explains how international copyright law works, how it affects developing countries, and how developing countries can affect it.

Case study

“I want to participate to an international exchange program, what should I know?”

Nadia works as a librarian in Mexico. She is very familiar with Mexican copyright law but wants to travel and work abroad. She plans to apply for an exchange program so she could spend six months working in another country. Her options include Ethiopia, Russia, India, and Belgium.

The exchange program requires that Nadia be familiar with the copyright law in the country where she will work. She must understand the following issues:

- general standards of protection of copyrighted works,

- protection of performers and producers of recordings,

- copyright protection of computer programs and databases,

- intellectual property rights of performers and of producers of phonograms,

- exceptions or limitations to the law that carve out creative freedoms.

Another librarian suggests that Nadia check whether her possible host countries have signed the same copyright treaties as Mexico. She tells Nadia that these treaties may set certain standards for the copyright law of everyone who signed it. However, she cautions Nadia that the laws may not be exactly the same, and that even if countries have signed the treaties they may not have been fully implemented.

The Rationale for the International System

As we saw in Module 1: Copyright and the public domain: an introduction, each country in the world has its own set of copyright laws. However, the flexibility that each country enjoys in adjusting and enforcing its own laws is limited by a set of international treaties. Why? Why do we need any international management of this field?

There are two traditional answwers to this question.

First, without some international standardization, nations might enact legislation that protects their own citizens while leaving foreigners vulnerable. Such discrimination was common prior to international regulation.

Second, it is easier for everyone to know the protections and freedoms of copyright law if there are some similarities across countries. It is especially beneficial for authors and artists to know what protections are available to them in a globalized world.

Finally, some copyright holders - especially media production firms - believe that developing nations would not enact strong domestic copyright law unless forced to by treaty. Representatives of developing nations strongly dispute this argument.

International Instruments

The simplest way to achieve these goals would be single treaty signed by all countries. Unfortunately, the current situation is more complex. Instead of one treaty, we now have six major multilateral agreements, each with a different set of member countries.

Each of the six agreements was negotiated within – and is now administered by – an international organization. Four of the six are managed by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), one by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and one by the World Trade Organization (WTO).

All six agreements have been created and implemented in similar ways. Typically, the process begins when representatives of states think that there should be international standards governing a set of issues. They enter into negotiations, which can last several years. During the negotiations, draft provisions are presented to the delegations of each state, which then discuss them and may propose amendments to their content. Once consensus has been reached, the states conclude the treaty by signing it. Thereafter, the governments of the participating countries ratify the treaty, whereupon it enters into force. From that moment onward, the signatory states assume obligations towards the other countries to implement the international agreement. States that did not sign the treaty when it was initially concluded may join the treaty later by accession.

None of the six treaties contains a comprehensive set of rules or standards for a copyright system. Rather, each one requires member countries to deal with particular issues in particular ways, but leaves to the member states considerable discretion in implementing its requirements. Nor do any of the treaties bind individual persons within the member countries until and unless the governments of those countries actually implement the standards with legislation.

Click here for more on the Stages of an international agreement.

Set forth below are brief descriptions of the six major treaties, with special attention to their impacts on developing countries.

Berne Convention

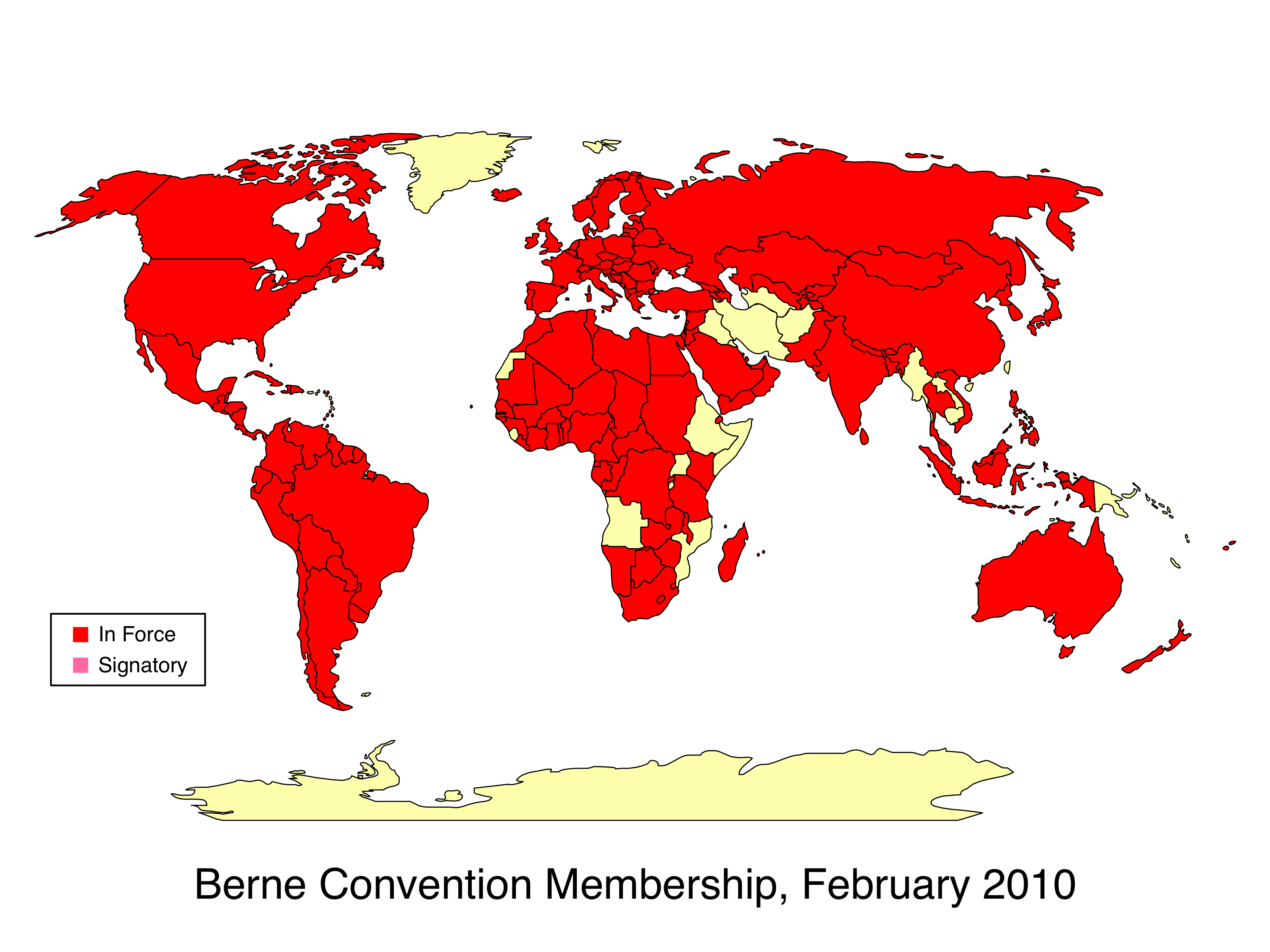

The uncertainty and confusion arising from the lack of a unified framework for the protection of copyright led ten European States in 1886 to sign the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (henceforth Berne Convention). Since then, a total of 164 countries have joined the Convention. Any nation is permitted to join. You can easily check to see if your country is a member of the Berne Convention. See bellow a map that indicates the countries that are today members

The Berne Convention established three fundamental principles. The first and most famous is the principle of the “national treatment,” which requires member countries to give the residents of other member countries the same rights with respect to copyright law that they give to their own residents. So, for example, a novel written in France by a French citizen enjoys the same protection in Italy as a novel written in Italy by an Italian citizen.

The second is the principle of “independence” of protection. It provides that each member country must give foreign works the same protections they give domestic works, even when the foreign works would not be shielded under the copyright laws of the countries where they originated. For example, even if a novel written in Belgium by a Belgian national were not protected under Belgian law, it would still be protected in Italy if it fulfilled the requirements for protection under Italian law.

The third is the principle of the “automatic protection.” This principle forbids member countries from requiring formal legal action as a prerequisite for protection. In other words, in Berne Convention countries, original works enjoy copyright protection automatically from the moment they are created. So, for example, the British author of a novel doesn’t have to register or declare her novel in France, Italy, Belgium or any other member state of the Convention; her novel will be automatically protected in all of these countries from the moment she has written it.

In addition to these basic principles, the Berne Convention also imposes on member countries a number of more specific requirements. For instance, they must enforce copyrights for a minimum period of time. The current minimum required by the Berne Convention is the life of the author plus 50 years. The Convention also requires its members to recognize and enforce a subset of the “moral rights” discussed in Module 1: Copyright and the public domain: an introduction.

When the Berne Convention was revised in Paris in 1971, the signatory states added an Appendix, which contained special provisions concerning developing countries. In particular, developing countries may, for certain works and under certain conditions, depart from these minimum standards of protection with regard to the right of translation and the right of reproduction. More specifically, the Appendix permits developing countries to grant non-exclusive and non-transferable compulsory licenses in respect of translation for the purpose of teaching, scholarship or research, and reproduction for use in connection with systematic instructional activities of works protected under the Berne Convention.

The Berne Convention outlines broad standards while mandating few specific rules. As a consequence each national legislature enjoys considerable flexibility in implementing the Treaty. For example, in the Berne Convention Implementation Act of 1988, the U.S. Congress adopted a “minimalist” approach to implementation, making only those changes to copyright law that were absolutely necessary to qualify for membership.

Furthermore, at the time that Berne the Convention was signed, the signatory countries did not establish an enforcement mechanism. This meant that member states had little power to punish another state that did not abide by the Berne Convention guidelines. As we will see later on, this situation partially changed for the members of the Berne Convention that also joined the World Trade Organization.

To learn more about the Berne Convention you may read its text or review the provisions of the Berne Convention.

Rome Convention (1961)

By 1961 technology had progressed significantly. Some inventions, such as tape recorders, made it easier to copy creative works. The Berne Convention only applied to printed works and thus did not help copyright holders defend against new technologies. To address this perceived need for strong legislative protection the Rome Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organizations was concluded by members of the WIPO on October 26, 1961. It extended copyright protection from the author of a work to the creators and owners of particular, physical embodiments of the work. These "fixations" include media such as audiocassettes, CDs, and DVDs.

{{{{{{{{{{{{{{{{{{{{THIS PARAGRAPH DOESN'T MAKE ANY SENSE AND I DON'T KNOW HOW TO FIX IT - CHRIS }}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}

The Rome Convention requires member countries to grant protection to the performances of performers, the phonograms of producers of phonograms, and the broadcasts of broadcasting organizations. However, once a performer has consented to the incorporation of her performance in a visual or audiovisual fixation, the provisions on performers’ rights have no further application. Equally important, the Convention allows member countries to create certain exceptions to the rights of performers, producers of phonographs, and broadcasting organizations – for example, to permit nonpermissive uses of a work for the purpose of teaching or scientific research.

{{{{{{{{{{{{{{{{{{}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}}

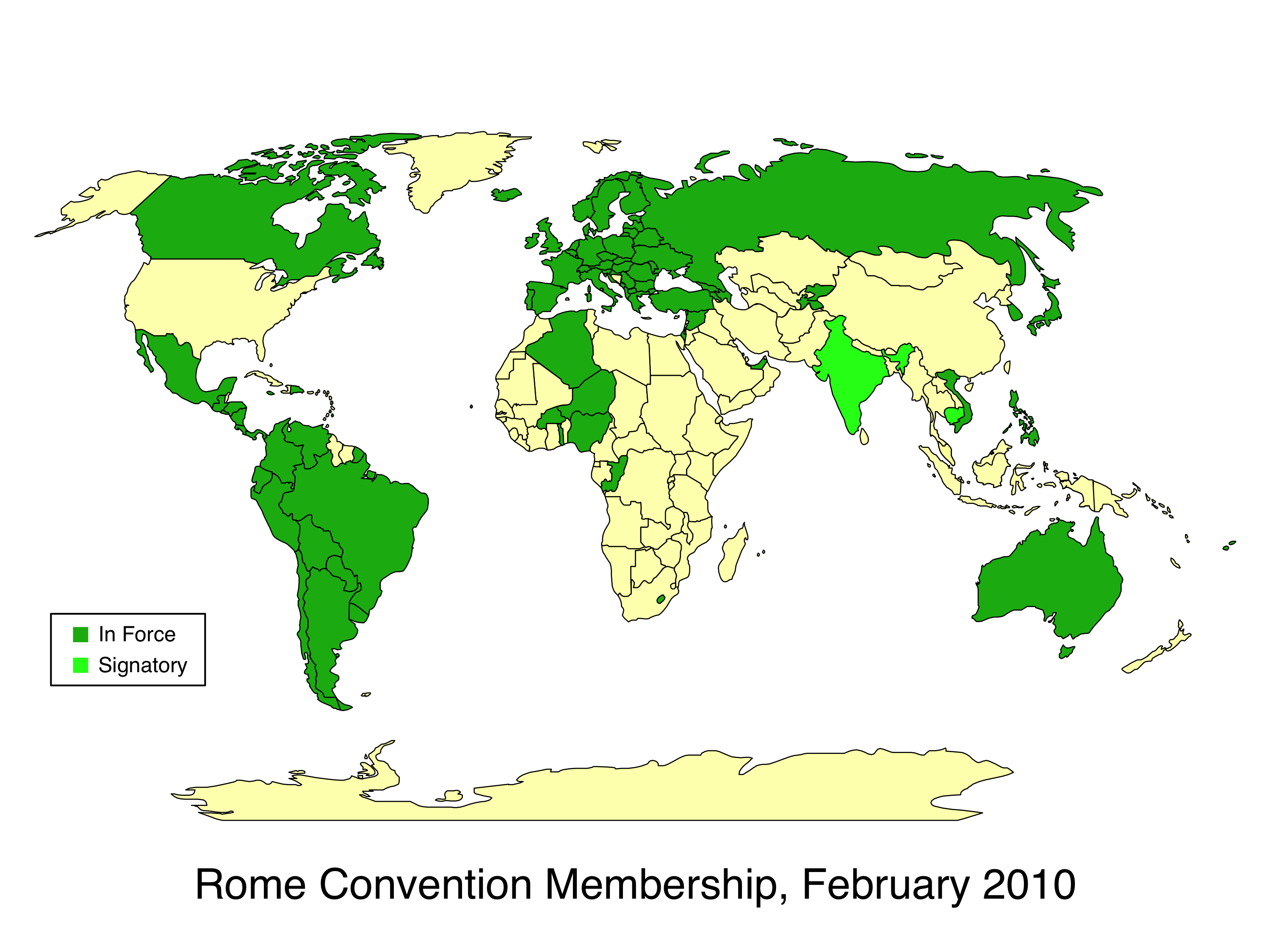

86 countries have signed the Rome Convention. Below is a map of the member states of the Rome Convention:

Membership in the Rome Convention is open only to countries that are already parties to the Berne Convention or to the Universal Copyright Convention. Like many international treaties, joining the Rome Convention has an uncertain effect on domestic law. Countries that join the convention may "reserve" certain rights with regards to certain provisions of the treaty. In practice, this has enabled countries to avoid the application of rules that would require important changes to their national laws.

For more information on the Rome Convention you may read its text or read more about the Rome Convention provisions.

WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT)

The way that copyright owners reproduce, distribute, and market their works has changed in the digital age. Sound recordings, articles, photographs, and books are commonly stored in electronic formats, circulated via the Internet, and compiled in databases. Unfortunately, the same technologies that enable more efficient storage and distribution of works also facilitate widespread copyright infringement. In order to protect copyright in the new technological era and to combat what has come to be called (misleadingly) “electronic piracy,” the governments of developed countries advocated and ultimately secured two treaties: the WIPO Copyright Treaty and the WIPO Performance and Phonograms Treaty.

The WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT) is a special agreement under the Berne Convention that entered into force on March 6, 2002. It is the first international treaty that requires countries to provide copyright protection to computer programs and to databases (compilations of data or other material).

The WCT requires members to prohibit the circumvention of technologies set by rightsholders for the protection of their work. These technologies might include encryption or “rights management information” (data that identify works or their authors, and that are necessary for the management of their rights).

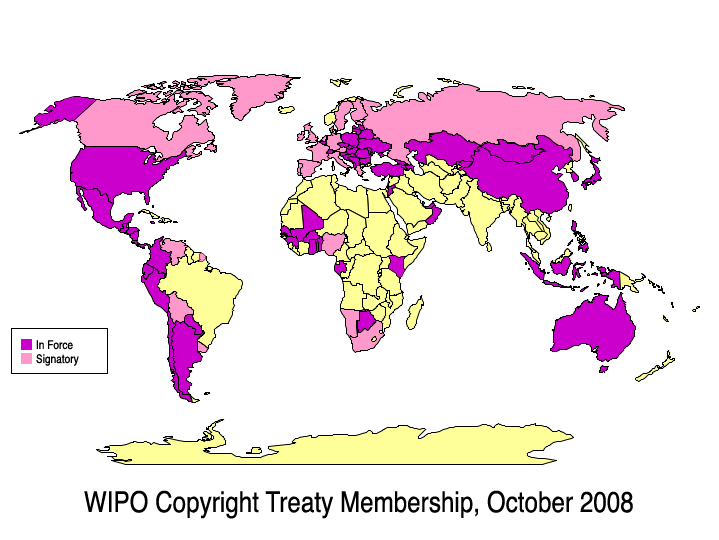

70 countries are party to the WCT. Below is a map of the member states:

For more about the WCT read its text or study the Examination of the WCT.

WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty (WPPT)

The WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treat (WPPT) was signed by the member states of WIPO. WPPT enhances the intellectual property rights of performers and of producers of phonograms. Phonograms include vinyl records, tapes, compact discs, digital audiotapes, MP3s, and other media for storing sound recordings).

The WPPT grants performers economic rights in their performances and in performances that have become fixed in phonograms. It also grants performers moral rights over these performances and their fixations. By contrast, producers of phonograms are only granted economic rights.

Both the WCT and the WPPT (like the TRIPs Agreement, which we will consider shortly) require members to quickly adopt and enforce the provisions of the treaty.

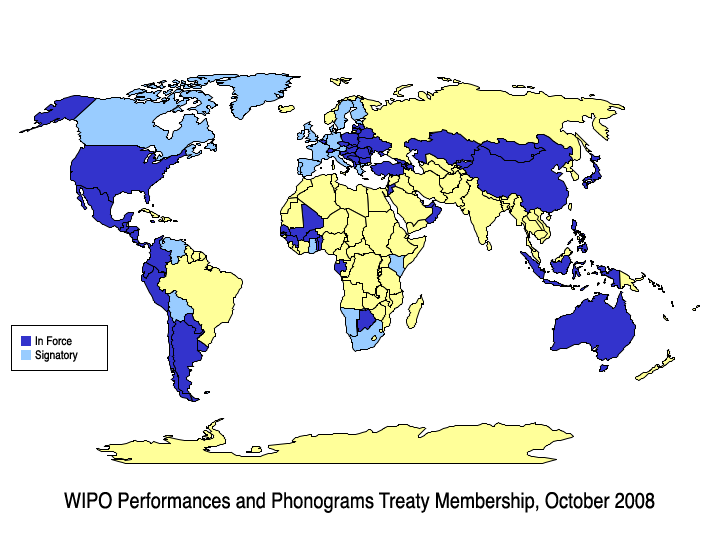

68 countries are party to the WPPT. Below is a map of the member countries:

For more about the WPPT read its text or consult the Examination of the WPPT.

Universal Copyright Convention

The Universal Copyright Convention (or UCC), was developed by UNESCO and was adopted in Geneva in 1952, as an alternative to the Berne Convention. It was developed in order to satisfy the desire of countries, such as the U.S.A. and the Soviet Union, to participate in some form of multilateral copyright protection without joining the Berne Convention.

The UCC’s provisions are more flexible than those of the Berne Convention, intended to accommodate countries at different stages of development and countries with sharply different economic and social systems. It incorporates the principle of national treatment and prohibits any discrimination against foreign authors.

Nowadays the importance of the UCC is minimal as most countries have acceded to the Berne Convention and almost all states in the world are either members or aspiring members of the World Trade Organization, and thus conforming to the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (which we will discuss in a moment).

For the text of the Treaty see http://www.ifla.org/documents/infopol/copyright/ucc.txt For a list of the countries members of the UCC see: http://portal.unesco.org/culture/en/files/7816/11642786761conv_71_e.pdf/conv_71_e.pdf

Click here for more on Examination of the UCC.

The Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs)

The Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) is an international agreement administered by the World Trade Organization (WTO) that establishes minimum standards for many forms of intellectual property protection, including copyright. The TRIPs Agreement was negotiated and concluded in 1994.

In terms of its substantive provisions, TRIPs adds little to the Berne Convention. It requires member countries to extend copyright protection to computer programs and data compilations – and thus extends the reach of the copyright regime. On the other hand, it excludes moral rights, which Berne, as we have seen, mandates.

The principal innovations of the Agreement pertain, not to the substance of copyright law, but to two issues involving remedies. First, unlike Berne, the TRIPs Agreement requires member countries to provide effective sanctions for violations of copyrights. Second, it creates a a dispute resolution mechanism by which countries can be forced to comply with their treaty obligations. In other words, TRIPs has teeth.

In an effort to balance public interests and the private interests of copyright owners, the TRIPs Agreement allows member states to establish limitations and exceptions to the exclusive rights of copyright holders – but only if they meet a set of related requirements known collectively as the “three-step test”.

Click here for more Information concerning the three-step test.

Finally, the TRIPS Agreement incorporates certain "flexibilities" with respect to member countries’ compliance with its requirements concerning copyright protection. These flexibilities aim to permit developing and least-developed countries to use TRIPS-compatible norms in a manner that enables them to pursue their own public policies, either in specific fields, such as access to pharmaceutical products, or more generally, in establishing the institutional framework that contributes to their economic development.

Click here for more Information concerning the flexibilities.

For the full text of the Agreement, see http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/t_agm0_e.html.

Click here for more on Examination of the TRIPS provisions.

The Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement proposal (ACTA, 2007)

These six multilateral treaties may soon be joined by a seventh. In October 2007, the United States, the European Community, Switzerland, and Japan simultaneously announced that they would negotiate a new intellectual property enforcement treaty, the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, or ACTA. Australia, the Republic of Korea, New Zealand and Mexico have since joined the negotiations.

Among other issues, the ACTA will deal with tools targeting "Internet distribution and information technology," such as authorizing officials to search for illegally downloaded music on personal devices at airports, or forcing Internet Service Providers to provide information about possible copyright infringers without a warrant.

Free Trade Agreements and Bilateral Investment Treaties

Multilateral agreements, such as the TRIPs Agreement, can provide effective protection to copyright holders worldwide, because they establish minimum substantive standards binding on large numbers of countries. However, they do not eliminate the incentives for bilateral treaties – either to address specific issues in which only two countries have an interest, or to enable interests groups within a powerful country to extract concessions from a weaker one. Such agreements are commonly known as free trade agreements (FTAs) or Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs).

Typically, such bilateral agreements either narrow the flexibilities that a developing country would enjoy under the TRIPS Agreement, or impose more stringent standards for copyright protection. For example, the US government has included anti-circumvention obligations in its bilateral FTAs with Jordan, Singapore, Chile, Morocco, Bahrain and Oman.

Click here for more Information on FTAs.

Perspectives for developing countries

Upgrading copyright legislation and enforcement worldwide can be viewed as the duty of governments towards their citizens, as copyright protection promotes the arts and rewards authors for their creative efforts. Arguably, granting an exclusive right in creative expression provides a necessary incentive to invest in the creation and distribution of expressive works and, thus, stimulates cultural advancement.

On the other hand, it has been argued that instituting the same rules for copyright protection in all countries, regardless of their development status, can be detrimental for the cultural development of developing countries. Most developed counties have powerful entertainment, education, and research industries, whereas developing countries typically import embodiments of the copyrighted works generated by those industries. Thus, the residents of developing countries have to pay more royalties and fees as a result of enhanced copyright protection. In addition, it has been argued that strict IP rules can restrict the ability of many governments to fulfil their human rights obligations, such as ensuring that their residents have fair access to educational goods.

The latter set of arguments have has prompted a growing number of developing countries to resist the imposition of the minimum standards of copyright protection set by the TRIPs agreement and the even harsher duties that are imposed on developing countries by FTAs. They call for a better balance between, on one hand, providing incentives to creators and rewarding their creative activities and, on the other hand, promoting access to knowledge and research, in order to spur economic growth and foster innovation in the developing countries.

WIPO Development Agenda

In 2004, Brazil and Argentina submitted to the WIPO General Assembly a proposal for a “development agenda.” In general, the proposal sought to ensure that WIPO in its various activities pay greater attention to the impact of intellectual property protection on economic and social development, the need to safeguard flexibilities designed to protect the public interest, and the importance of promoting “development oriented” technical cooperation and assistance. The text of Brazil’s and Argentina’s proposal is available at: http://www.wipo.int/documents/en/document/govbody/wo_gb_ga/pdf/wo_ga_31_11.pdf. Additional proposals in support of a WIPO Development Agenda were submitted by other member states and organizations, such as Chile, the Group of Friends of Development, the Africa Group, and Colombia.

This initiative has made considerable progress. In the 2004 WIPO General Assembly, states agreed to hold a series of intergovernmental meetings to examine the proposals for a development agenda. Substantive reform proposals to establish a Development Agenda for WIPO passed during the 2007 General Assembly. The 45 development recommendations currently on the development agenda are available at: http://www.wipo.int/ip-development/en/agenda/recommendations.html

Organizations representing librarians have had a significant voice in the negotiations of the Development Agenda. Joint statements of the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA), the Library Copyright Alliance (LCA), and Electronic Information for Libraries (eIFL) are available at: http://www.eifl.net/cps/sections/services/eifl-ip/issues/wipo-development-agenda

Click here for more Information on the WIPO development agenda.

The access to knowledge treaty proposal

The Argentina-Brazil proposal for a development agenda gave rise to a debate concerning whether WIPO should ensure effective technology transfer from developed to developing countries. Nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), academics, and researchers shared the concerns expressed by developing countries that some aspects of the copyright system were actually impeding innovation instead of promoting it and were creating disadvantages for the developing countries. This reaction to WIPO’s current policies took the form of a movement calling for equality among citizens from developed and developing countries as regards access to knowledge; it has come to be known as the “access to knowledge” or “A2K” movement. Librarians’ organizations, such as eIFL, were pioneers in the advocacy of people’s “right to knowledge” and have called upon WIPO to establish minimum exceptions and limitations to copyright protection.

One outgrowth of the movement has been a proposal for a United Nations treaty, the current draft of which is available at: http://www.cptech.org/a2k/a2k_treaty_may9.pdf. The treaty proposal aims to “protect and enhance access to knowledge, and to facilitate the transfer of technology to developing countries.” It includes a list of occasions when copyright holders should not be able to invoke their exclusive rights, such as:

· The use of works for purposes of library or archival preservation, or to migrate content to a new format.

· The efforts of libraries, archivists, or educational institutions to make copies of works that are protected by copyright but that are not currently the subject of commercial exploitation, for purposes of preservation, education, or research.

· The use of excerpts, selections, and quotations for purposes of explanation and illustration in connection with not-for-profit teaching and scholarship.

· The use of works, by educational institutions, as primary instructional materials, if those materials are not made readily available by right-holders at a reasonable price.

In addition, the proposal advocates a First Sale Doctrine for Library Use, stating that “a work that has been lawfully acquired by a library may be lent to others without further transaction fees to be paid by the library.” Finally, the A2K treaty proposal introduces provisions in support of distance education and other provisions accommodating the rights of persons with disabilities.

Librarians and library patrons aren’t the only ones who could benefit from the A2K treaty. The proposal includes rules protecting Internet Service Providers from copyright liability, and also mitigates the strict circumvention prohibitions that are applied by the international treaties. Nonoriginal and orphan works would be left in the public domain under the treaty proposal, and people would be afforded access to publicly funded research works, government works, and archives of public broadcasting. Finally, the A2K treaty proposal also includes provisions on patent protection, anticompetitive practices, and transfer of technology to developing countries.

Click here for more Information on the A2K Treaty proposal.

Back to the case study

Nadia knows that Mexico is a member of the Berne Convention, WIPO, Rome Convention, WCT and WPPT. After checking the online databases provided in the WIPO website she found out the following about the countries where she is interested in working:

- Ethiopia isn’t currently a member of any of the international treaties on copyright protection. Thus, the national government of that country has the freedom to regulate copyright independently from other states in the rest of the world. Therefore Nadia cannot have an understanding of the copyright legislation in Ethiopia, unless she had studied Ethiopian copyright law. - Russia has signed the Berne Convention as well as the Rome Convention, but isn’t yet a member of the WTO. Because both the Berne and the Rome Convention lack an effective enforcement mechanism, other signatory states have little leverage to force Russia to comply with their obligations. Furthermore, Rome Convention affords states that join the treaty the liberty to make reservations with regard to the application of certain provisions.

In addition, Russia has signed the WCT, but that treaty hasn’t entered into force yet. In other words, although Russia has undertaken an obligation towards the other signatory countries to implement the treaty, it hasn’t yet been incorporated into Russian law, and its content is not binding on Russian citizens. Russia isn’t a member of the WPPT.

- India is a member state of the Berne and Rome Conventions and is also a member of the WTO. All members of the WTO are bound by the TRIPS Agreement, which imposes on member countries the obligation to enforce copyright adequately in their own territories, an obligation enforced by the WTO dispute settlement procedure. The TRIPs Agreement requires WTO members to comply with the substantive provisions of the Berne Convention, with the exception of the recognition of moral rights. Therefore, Nadia can rely on the fact that the substantive requirements for copyright protection in Mexico and India are similar. On the other hand India hasn’t signed the WCT and the WPPT. Thus Nadia cannot know how India regulates copyright protection of computer programs and databases and the intellectual property rights of performers and of producers of phonograms.

- Finally Belgium is a member of all of the aforementioned international treaties on copyright protection. As a result, Nadia can only apply for the exchange program in Belgium, as she knows the basic framework on copyright protection in Belgium, based on her knowledge of Mexican copyright law.

Assignment and discussion questions

Round 1 questions

1. Which international treaties in the field of intellectual property law has signed and ratified your country? Feel free to use the links and maps provided in this module to help you.

2. If your country were a member of the Berne Convention, could your national legislator issue a law according to which copyrighted works would be protected for a) 120 years b) 25 years? Why?

3. Imagine that your country is a member of the Berne Convention, but not of the WTO. 3a. Could your country’s legislator decide that authors of third countries should first register their works in a national archive in order for the works to be protected in your country? 3b. Could members states to the Berne Convention react to this requirement to protect the rights of their authors? 3c. Could they react if your country was a member of the WTO?

4. Imagine that your country, as well as Atlantis, are members to the Rome Convention. Could your legislator permit that music teachers in your country use freely in their classes recorded performances of singers from Atlantis? Could Atlantis demand from your country to oblige the music teachers to pay royalties to the Atlantian singers?

5. Atlantis has just signed and ratified the WIPO Copyright Treaty and now the national legislator wants to issue a law that will implement the treaty. Atlantis had never provided copyright protection to computer programs in the past and, as it is a country that only imports computer software from third countries, the national legislator believes that it is the in the interest of the Atlantians to provide as little protection to computer programs as possible. Skim the WCT and find the provision that would enable the national legislator to allow Atlantians, under certain circumstances, to freely use computer programs.

6. List the advantages and the disadvantages of enhanced copyright protection for creative works.

7. Do you think that both developed and developing countries should have the same rules for copyright protection? Why or why not?

8. Read article 3-1 of the draft text of the A2K treaty: http://www.cptech.org/a2k/a2k_treaty_may9.pdf Comment on the importance of one or two provisions for the missions you perform as a librarian.

Round 2 questions

Please read comments on A2K treaty proposals that your colleagues provided to Round 1 question 2, and comment on one (or more) of them. You may give more examples based on situations you faced at work, or projects you could develop.

Quick Access

The textbook modules are available both on Connexions and on this wiki