Alternative Energy/Paper

The Political Economy of Intellectual Property in the Emerging Alternative Energy Market

UNDER DEVELOPMENT - THE STRUCTURE MAY CHANGE

Introduction

The alternative energy field represents a unique case for studying the trends regarding the political economy of intellectual property (IP) in an emerging market. Some of the technology can be considered mature; however many are the barriers - technical, socio-cultural, political or related to funding - that justify a young market in many countries. These issues are at the center of our research under the Industrial Cooperation Project at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University (ICP).[1] This research is part of a broader project being led by Yochai Benkler, Professor of Entrpreneurial Legal Studies at Harvard Law School. Within the ICP, we are seeking to understand the approaches to innovation in the alternative energy[2] sector looking specifically at wind, solar and tidal/wave technologies. The intention is to map the degree to which open and commons-based practices are being used compared to proprietary approaches.

In this sense, our research is guided by the definition of the “commons” molded by Prof. Benkler, who asserts: commons are a particular type of institutional arrangement for governing the use and disposition of resources. Their salient characteristic, which defines them in contradistinction to property, is that no single person has exclusive control over the use and disposition of any particular resource. Instead, resources governed by commons may be used or disposed of by anyone among some (more or less well defined) number of persons, under rules that may range from ‘anything goes’ to quite crisply articulated formal rules that are effectively enforced. Commons can be divided into four types based on two parameters: The first parameter is whether they are open to anyone or only to a defined group. The second parameter is whether a commons system is regulated or unregulated. Practically all well studied limited common property regimes are regulated by more or less elaborate rules - some formal, some social-conventional - governing the use of the resources. Open commons, on the other hand, vary widely. (Benkler, 2003, 6)

We began our research with the intention of limiting our scope to the US only, but given the global scope of the alternative energy market, and the fact that almost all the market leading companies have grown in foreign countries where the markets for this technology have been biggest and which can be considered historical centers of technology innovation, we chose to include Germany, Denmark, and Spain. Among the countries considered emerging economies, we decided to look at China for the geopolitical implications relating to its relationship with the United States. We did not look into other developing countries, however, these will be briefly addressed under the section related to international negotiations around climate change. Under this context, developing countries will appear as actors asking for technology transfer and technology cooperation models, under the justifications of the need for energy to fuel industrial growth and universal access to electricity.

The European countries represent three of the biggest markets for wind and solar technology, and are home to some of the biggest companies producing the technology.[3] China is the newest and biggest market entrant into the solar market, and could become the biggest producer of this technology over the next few years.[4]

We also decided to broaden the scope of the research by exploring the development of governmental policies for alternative energy technology development and innovation as they relate to the global debates about appropriate governmental responses to Climate Change.

Thus, our goal is to follow the alternative energy market and identify the levels of openness and closedness in the areas where innovations are happening, dialoguing with a bibliography that covers the political economy of intellectual property and how intellectual property impacts innovation. We will also be looking for the presence of commons-based arrangements of knowledge production within the alternative energy innovation process to determine if they appear, and if so, where and how they appear.

We chose wind, solar and tidal/wave technologies with the expectation that we would find variations among their approaches to openness and closedness, since the technologies represent different levels of maturity and patenting activity. The maturity can be measured both by the stage of development of the technology and the stage of development of the market. For instance, wind is considered a mature technology because it is fairly well understood, and the cost of generating electricity with wind turbines is closer to the cost of conventional sources of fossil fuel generated electricity (see Figure 10) - though it is still more expensive.[5] Solar photovoltaic (PV) technology is less mature and can be quite expensive, therefore the research and innovation around solar PV technologies is sure to play a critical role in bringing its costs down and generating more efficient technology.[6] Tidal/wave technology is relatively immature compared to wind and solar, and is mostly in the demonstration phase at this time. Only a few small projects around the world - such as a tidal barrage, which was constructed at La Rance in Brittany, France in the 1960s (Bryden 2004, 139) - are generating consumer electricity. We go into more detail on the maturity of these technologies in Section 1.2.5.e, The Maturity of Solar, Wind and Tidal/Wave Technologies.

These technologies are a subset of the many alternative energy technologies that exist, and they are all representative of energy supply technologies, meaning they are focused on bringing energy to a point of final use.[7] There is another set of technologies called energy end-use technologies that are part of our discussions of the cleantech industry as a whole. These technologies are concerned with the most efficient use of the supplied energy. Examples are home appliances, automobiles, and light bulbs.

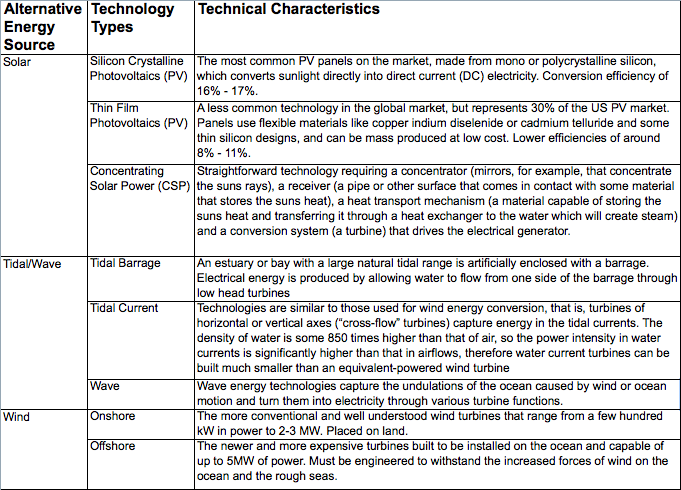

Within our three focus technologies - wind, solar and tidal/wave - there are a variety of subset technologies. Figure 1 provides descriptions. These energy supply technologies should not be confused with their close relatives listed below, which are not part of our research:

- Solar thermal - uses the suns energy to heat water for home and commercial use.

- Solar heating and cooling - uses building design to take advantage of the sun’s direct heat and energy to efficiently heat and cool buildings at different times of the day and during different seasons.

- Wind or tidal/wave technologies used for mechanical work rather than for conversion to electricity.

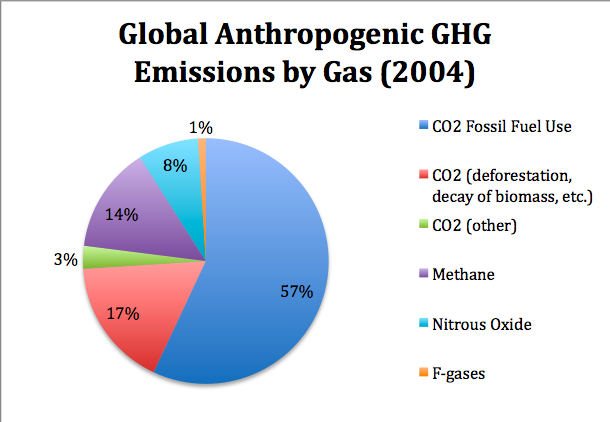

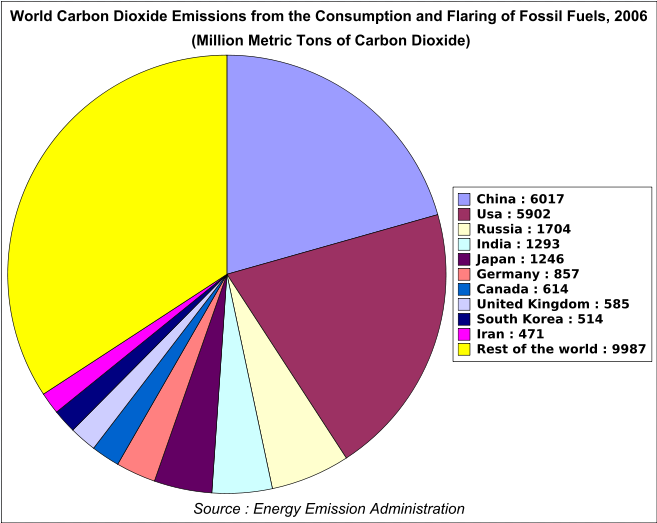

We excluded these technologies because they are less common than the energy supply technologies we are researching, and because energy supply technologies can have a bigger impact on reducing global carbon emissions by reducing the use of coal for electricity generation. Reducing the use of coal can facilitate the shift to a lower emissions electric plug-in vehicle market thereby reducing the world’s dependence on both coal and oil the biggest global climate change contributors - as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1

Technologies for electrical generation from solar, wind and tidal/wave energy

Sources: Author illustration based on information from: (Bosik 2009; Capello 2007; Capello 2008; Carlin 2004; Lemonis 2004; Luzzi & Lovegrove 2004; Perlin 2004)

Figure 2

Global Anthropogenic GHG emissions divided by type of gas

Source: (PEW 2009)

Alternative Energy Technology History

It is important to note that the term "alternative" energy sources is a contemporary moniker that stems from the fact that these energy technologies are alternatives to the mainstream energy sources such as coal, natural gas, oil, and nuclear fission. The 1973 oil crisis spurred the first global push for these alternative energy sources as high petroleum prices threatened the world's (and more specifically the developed world and the United States in particular) access to cheap and plentiful sources of energy. In October 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) announced an oil embargo that would limit or stop oil exports to the US and any other country that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur war. [3] The result was a steep increase in the price of oil, and oil shortages in the affected countries. Soon after the embargo began the 1973-74 stock market crash followed, which had debatable links to the embargo, but nonetheless influenced governments in their attempts to address their energy supply security concerns. The affected countries responded to the oil crisis by exploring policy and investment strategies to reduce their dependence on the Middle East for their oil, and alternative energy technologies secured a prominent role in these reactions. In the United States, the presidency of democrat Jimmy Carter marked a period of significant investment in alternative energy sources as well as the introduction of government policies that supported the development and diffusion of these technologies.

While the origins of alternative energy supply technologies are all based in the 1800's, the practice of using the wind, sun, and tides/waves as sources of energy for work, are much older. Wind was used to power sailboats up to 5,500 years ago, and there is evidence of windmills for mechanical work in India 2,500 years ago. (Sorenson 1991, 8) Solar energy is the basis of most energy on earth, including the energy in plants from photosynthesis, solar thermal heating, the fossil remains of organic material in oil and coal, and wind, which is created when air, heated by the sun, rises and cold air from another area moves into that space. (Carlin 2004, 348) Using moving water for power can be traced back to 250 BC. (Sorenson 1991, 8)

a. Wind technologies

Wind turbines for electrical generation were first developed simultaneously in the US and Scotland around 1887. Charles Brush was an American inventor who developed an electric arc light system in his home laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio. In order to test the lights he needed his own dedicated source of electricity, so he built a 60 foot wind turbine with an electric generator in it and wired it to a collection of batteries to store the energy. This wind turbine successfully powered his lab for 15 years. While Brush filed many patents for his lighting systems, he never patented his wind turbine. (Righter 1996, 52) The true reason for this is unknown, but some historians have theorized that Brush didn't see a market for wind turbines in Cleveland where the wind was inconsistent on the whole, or perhaps, as the article in Scientific American about his personal wind turbine stated, the capital cost and operations and maintenance costs were too high to make the technology marketable. (Righter 1996, 53) While Brush is credited with the first electrical wind turbine, a Danish inventor named Poul La Cour was concurrently inventing commercial scale turbines. By 1906 there were 40 windmills generating electricity in Denmark, which marked the beginning of the country’s relationship, and innovation edge, in wind technology. (Pasqueletti 2004, 422-423)

Soon afterward, both Germany and the UK started to experiment with wind electricity and install their own turbines. Meanwhile in the US, some small companies were marketing small turbines for electrical generation on rural farms, but the development and adoption of the technology did not match Europe. By the 1930’s the US had a burgeoning market for small rural off-grid wind turbines, but that changed in 1936. The Rural Electrification Act was passed that year, which was tasked with connecting rural areas to the electrical grid. It was so successful that every US electric wind turbine manufacturer had closed its doors by 1957. In Denmark during this same period, wind power was spreading throughout the rural areas providing off-grid electricity. (Pasqueletti 2004, 423)

In 1950, a Danish engineer named Johannes Juul began testing a prototype wind turbine for a Danish utility. The design used some technological elements from the earlier designs of F.L. Smidth, the founder of a successful Danish wind turbine manufacturing company, which had integrated aerodynamics into La Cour’s designs. Juul ultimately built a three-bladed wind turbine that was installed at Gedser, Denmark in 1956. It was in regular service from 1959 - 1967, and became the model for the wind turbines manufactured in Denmark in the late 1970’s after the oil crisis. The design is now referred to as the "Danish concept," which is defined as "a horizontal axis, three-bladed rotor, an upwind orientation, and an active yaw system to keep the rotor oriented into the wind." (Steele 2009, 156) A wind rush began in California in the 1980s, which was also in part due to reactions to the oil crisis, and Denmark was poised to dominate the market in the US. Denmark shipped thousands of wind turbines to California between 1980 and 1985, and after the market in California crashed, Denmark started selling thousands more to Germany. All of these turbines were technologically derived from Juul’s "Danish concept" turbine. (Pasqueletti 2004, 426; Steele 2009, 156) It has been observed that during these early days of wind development in Denmark, the companies did not follow formal R&D activities, but instead relied on practical experimentation and hands-on work to develop core competencies. Over time, traditional R&D functions emerged. (Andersen & Drejer 2005, 3)

In the US during the 1970s, NASA funded research at the Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, to refine the design and function of electrical wind turbines.[4] Soon after the oil crisis, the US government started to fund the Federal Wind Energy Program, and research and development (R&D) funds were devoted to the cause. Research was also conducted at Sandia National Laboratories in California. In the 1980’s the government drastically reduced their R&D funding for wind and other alternative energy technologies (for reason that are explained later in this paper) and shifted the focus of alternative energy developments over to tax credits. (Weiss & Bonvillian 2009, 127-129; Lewis & Wiser 2007)

The wind technology market shows a high degree of consolidation with a small group of companies controlling the majority of the market for large commercial scale wind turbines (see Figure 7 later in the paper). Patent battles have been common, with GE, the largest US manufacturer of wind technology, asserting their patents aggressively in an attempt to keep other companies out of the US market. To date they successfully kept Germany's Enercon out of the market based on a patent infringement case for their variable speed wind turbine technology. They are currently suing Mitsubishi for patent infringement of the same variable speed turbine technology. (de Vries 2009, 1) In a recent report on patents in alternative energy technologies, the authors pointed out that the top four wind turbine manufacturers own 13% of the technology patents and control 57% of the market for wind turbines. (Lee et. al. 2009, viii) This is by far the most consolidated market within the various alternative energy technologies.

The market for wind turbine components is quite competitive. Various original equipment manufacturers (OEM's) may produce wind turbine blades, gearboxes, generators, bearings, towers, and electronic control equipment. This leads to a complicated interconnected market with lots of potential for new innovation in these various parts. Typically, the OEM market is limited to medium-scale turbines of less that 1 MW in peak capacity. (Lako 2008, 35)

Modern wind turbines are manufactured with three-bladed rotors with diameters of 70 to 80 meters mounted on top of towers with 60 to 80 meter heights. A typical turbine in the United States in 2008 produces more than 1.5 MW of electrical power. The power output of the turbine is controlled by rotating the rotor blades to change the angle of the wind hitting the blade. This is referred to as “controlling the blade pitch.” The turbine is pointed into the wind by rotating the nacelle about the tower, which is called “yaw control.” (Bosik 2008, 50)

There are four major component assemblies in modern wind turbines: the rotor, nacelle, tower, and balance of system. The rotor consists of blades used to harness wind energy and convert it into mechanical work, and a hub that supports the blades. In addition, most wind turbines have a pitch mechanism to rotate and change the angle of the blades based on the wind speed as described above. The nacelle is the structure that contains, encloses, and supports the components that convert mechanical work into electricity. These components include generators, gearboxes, and control electronics. The tower supports the rotor and nacelle, and raises them to a height where higher wind speeds maximize energy extraction. Additional balance-of-station components at ground height are required to gather, control, and transmit power to the grid interconnection. (Bosik 2008, 50)

There is no single component that dominates turbine cost, though, the rotor is usually the highest cost item on the turbine and must also be the most reliable. Towers are normally the heaviest component and weight reductions would benefit the price and performance, but lightening the rotor or tower-top weight has a multiplier effect throughout the system including the foundation. The nacelle refers to all of the wind turbine structures that house its generating components, and includes the following: measuring controlling, power transmission, circuits, fans/blowers, iron foundries, all other plastics, motors and generators. (Bosik 2008, 50) · An outer frame protecting machinery from the environment · An internal frame supporting and distributing weight of the machinery · A power train to transmit energy and to increase speeds of the shaft · A generator to convert mechanical energy into electricity · A yaw drive to rotate the nacelle on the tower · Electronics to control and monitor operation (Bosik 2008, 50)

The top ten companies in the wind industry account for 85% of the global turbine market [5] The market leader is Vestas (Denmark) with 19.8% of the market but GE Energy (USA) is growing quickly and has nearly caught up with 18.6% of the market. [6] The biggest change to this distribution is likely to come from Chinese manufacturers who are expanding and bringing down the cost of manufacturing turbines. [7] Emerging market players like China and India are changing the make-up of turbine manufacturing since, as of 2005, eight of the top ten wind turbine manufacturers were in Europe and they represented 72% of the global market, or a value of US$23.3 billion. (Gallagher 2009, 93)

b. Solar photovoltaic (PV) technology

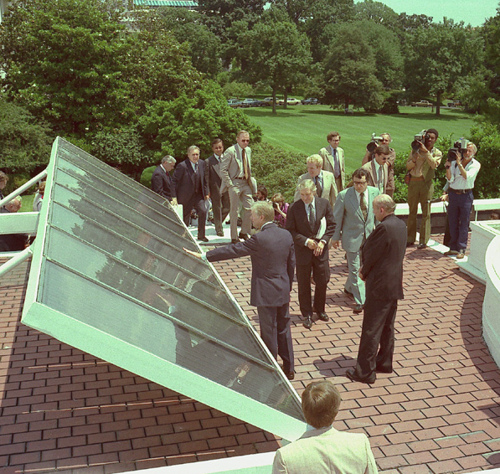

The solar photovoltaic (PV) effect was discovered in 1839 by Alexandre-Edmond Becquerel. He observed that when selenium was exposed to sun a small electrical current was created. In 1888 Edward Weston received the first U.S. patent for the solar cell, and in 1901 Nicola Tesla received a US patent for a "method of utilizing, and apparatus for the utilization of, radiant energy". [8] Solar PV panels remained undeveloped until 1953 when the first commercial panels were manufactured at Bell Laboratories after one of the lab’s scientists discovered that silicon could be used in place of selenium as a more efficient material for creating electricity. The US government took a keen interest in the technology for use in the space program, and funded PV developments for that purpose. (Sorenson 1991, 9; Perlin 2004, 616-617) Throughout the 1960s solar research was funded by governments and in research labs, mostly for applications in the space industry for satellites and space-based vehicles. When the oil crisis of the 1970s occurred the US government founded the Solar Energies Research Institute - later renamed the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) - to develop new, lower cost solar energy technologies. US President Jimmy Carter further supported the R&D efforts of the solar industry by allocating $3 billion for solar energy research, and installing a test solar water heater in the White House as well as a solar PV array on the roof. (Is there any information on the IP policy in force by then? Or all the results were patented? If patented do we have numbers or examples?) These developments came to a halt in the 1980’s when President Ronald Reagan took office and drastically cut the R&D funding for solar energy, while also removing the solar PV array from the roof of the White House. (Bradford 2006, 98) Image 1 below shows the solar installation on the White House roof during the Carter Administration.

The US represented 80% of the global solar energy market at the time, and soon, the other industrialized countries followed the United States’ lead. (Bradford 2006, 98) Throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s solar research was limited to research universities, inventors and state energy agencies, and the assets and patents of the original solar energy technology companies were purchased by large oil companies like Mobil, Shell, and BP. (Bradford 2006, 98)

Image 1

US President Jimmy Carter showing off the new solar PV panels on the roof of the White House in the 1970's

Source: Flickr [9]

Research conducted at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government [8] identified the source of funding for 14 of 20 key innovations in PV technology developed over the past three decades (1970s, 1980s, 1990s). It was discovered that only one of the 14 was fully funded by the private sector, and 9 of the remaining 13 were financed with public funding, while the other 3 were developed in public-private partnerships. The researchers assumed that the innovations for which they could not identify funding sources were developed in the private sector. (Norbeg-Bohm 2000, 134)

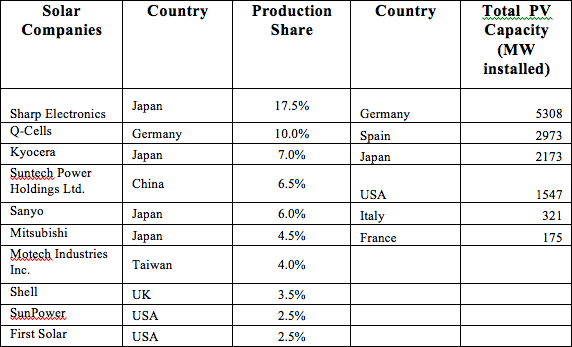

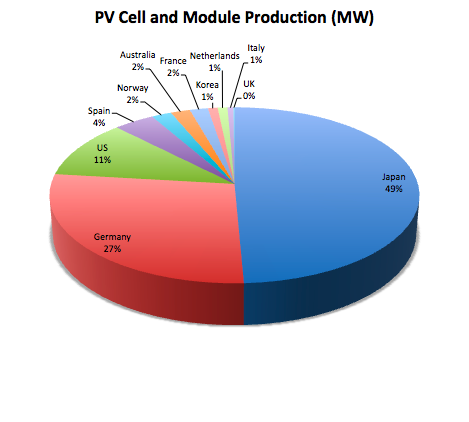

Over the last twenty years, the market for solar technology has grown in foreign countries while still moving slowly in the US. Other countries - especially Japan and Germany - have taken the lead in technology development and installation of solar technology. Solar is still an expensive technology with a small but growing global market share. Countries such as Spain and Germany have used generous renewable energy subsidy programs - referred to in this paper as demand-pull policies - to rapidly install massive amounts of solar PV technology. China, while a leading producer of solar PV technology (as shown in Figure 3), has only recently begun to implement solar PV subsidy programs that will help to encourage the adoption of the technology on a larger scale. (Gipe 2009, 1) Figure 3 shows a comparison of the countries with the top production share and the countries with the most installed PV capacity, while Figure 4 shows the percentage of PV cell and module production in IEA countries (excludes China).

Figure 3

Comparison of Solar PV production market share by country and total installed capacity by country

Source: Authors' illustration based on (SEIA 2008; REN21 2009; Cappello 2008)

Figure 4

PV Cell & Module Production in IEA countries (excludes China and India)

Source: Authors' illustration based on (Lako 2008, 33)

The researchers at Harvard's Belfer Center came to the following conclusions on solar PV innovation in the US:

"In sum, the strengths of the U.S. Solar R&D program have been: (1) a parallel path strategy, (2) collaborations between industry, universities, and national labs including public-private partnerships with cost sharing, (3) attention to the full range of RD&D needed, from basic scientific work through to manufacturing, including attention to all components, materials, cells, and modules. Critiques of the solar PV R&D program include: (1) a lack of consistency in funding that created fits and starts in technological progress, and (2) concern that manufacturing R&D was not begun soon enough. Overall, the trend has been to increase attention to manufacturing issues and to increase public-private partnerships, including growth in the level of private sector cost sharing." (Norberg-Bohm, 2000, 135)

There are a few different types of Solar PV technologies, which vary in cost and efficiency. [9] The most commonly available PV panels on the market are crystalline silicon cells. Mono-crystalline cells make up 33% of the global market and can achieve up to 18% efficiency, while polycrystalline cells make up 56% of the global market and, while cheaper than mono-crystalline cells, they can achieve up to only 15% efficiency. (Lako 2008, 31) Future price drops are expected due to economies of scale, reductions in the price of silicon, R&D investment in the technology, and learning through project installation experience. There are also thin-film solar PV cells which cost less than the cells mentioned above, but have lower efficiencies (8% - 12%), making the return on investment calculations difficult. Thin film silicon cells represented 8.8% of the global market in 2003, while thin-film copper iridium di-selenide cells held 0.7%. (Lako 2008, 31) R&D investments in experimental multi-layer cells and low-cost polymer based cells, as well as cells made with quantum dots and nano-structures, hold promises for more efficient and cheaper future cells, but will take time to reach market deployment. (Lako 2008, 31)

Electricity generated from PV panels is on average about $0.30 per kWh, much more expensive than the average retail price of electricity of ~$0.10 per kWh. [10] (Kammen 2004, 401)

Annual global Solar PV growth has been in the 40% - 60% range since 2000 and resulted in 3,800MW of PV capacity by 2007. (Cappello 2008, 6) Global Solar PV production almost doubled in 2008 rising to 7.3 GW an 80% increase over 2007. [11] After years of market domination in Japan, China is now the leading producer of solar cells, with an annual production of about 2.4 GW. China could secure about 32% of world-wide production capacity by 2012 if this trend continues. [12] Behind China's production prowess are Europe with 1.9 GW, Japan with 1.2 GW and Taiwan with 0.8 GW.[13] European PV production has grown on average by 50% per annum since 1999 and its market share has increased to 26% in 2008. [14] The US is the leader in thin film PV technology, which represents only 7% of global production (170MW). (Capello 2008, 6)

In 2009 the global economic crisis exacted a heavy toll on solar companies due to the high cost of the technology, and therefore the high cost of the projects. [15] The credit crunch slowed project developers acquisitions of loan money and caused a precipitous drop in tax equity investing [10]

c. Concentrating Solar Power (CSP) Technology

Solar PV’s lesser known and less common relative is Concentrating Solar Power (CSP). Solar thermal furnaces that generated sufficient heat to produce steam - the basis of a CSP plant - were first developed in the eighteenth century and used in small scale applications in the US and France during the 1860’s. (Sorenson 1991, 8) Today, the US is seeing renewed interest in CSP plants, while the current supply of CSP generated electricity comes from a number of 80MW (megawatt) plants in Southern California, which were built in the late 1980’s. (Luzzi & Lovegrove 2004,1)

Nevada, a state with very strong renewable energy support policies, [11] initiated the first long term power purchase agreement of concentrating solar electricity signed between two public utility companies and the US solar developer Solargenix (which is now owned by a Spanish solar company named Acciona). The developer built the second largest CSP plant in the world with 75 MWe (Megawatts of electricity) trough plant that was completed in 2007. It uses 760 parabolic troughs and has over 300,000 m2 (square meters) of mirrors and limited energy storage to guarantee the capacity. (Philibert, 2004, 14); [16]

In June 2004, the Governors of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah, Texas and Colorado voted a resolution calling for the development of 30 GW of clean energy in the West by 2015. Of this alternative energy development, 1 GW would be of solar concentrating power technologies. The US Department of Energy decided to back this plan and to contribute to its financing in June of 2004. (Philibert, 2004, 14; Luzzi & Lovegrove, 2004, 669) CSP is a mature and very well understood technology with growing adoption in the US.

New innovations in CSP technology are enabling greater growth and cheaper power production. Much of the innovation in CSP technology has taken place in the heat transport material, of which a number currently exist: (Philibert, 2004, 14; Luzzi & Lovegrove, 2004, 669)

- Synthetic heat transfer oil - Oil is effective, but suffers from decomposition due to high heat. Oil also creates an environmental and fire hazard if it leaks.

- Air - Air is reportedly quite effective.

- Molten Salt - very effective, especially for heat storage overnight in insulated tanks (this can allow electricity generation when the sun is down). The downside is that the salt can be corrosive and reacts with air or water.

- Chemical - Thermochemical cycles with fluid reactants can provide very effective heat transport and storage for use when the sun is down.

CSP plants are very effective and quite cheap in comparison to PV, while still a bit more expensive than conventional gas and coal electricity plants. At 80MW, the plants in California are generating large quantities of electricity at a levelized electricity cost of $0.12 - $0.16 per kWh, a fairly competitive cost compared to a US "Average Retail Price of Electricity to Ultimate Customers" of ~$0.10 per kWh. [17]

d. Tidal/wave technologies

Tidal and wave technology are a subgroup of Ocean Technologies.[12] There are many different established tidal and wave technology designs in use or in various phases of testing. It is believed that the world could cover a significant portion of its electricity demand from tidal and wave energy sources. The potential global energy contribution to the electricity market from wave technology is estimated to be approximately 2000 TWh/year, which is equal to 10% of world electricity consumption. The global tidal range energy potential is estimated at approximately 3000 GW, with around 1000 GW (~3800 TWh/year) available in shallow waters. Tidal energy conversion technologies are predicted to supply up to 48 TWh/year from sites around Europe. While other large tidal current resources are yet to be explored worldwide. While research and development on ocean energy exploitation is being conducted in several countries around the world, the technologies for energy conversion have not yet progressed to the point of large scale electricity generation. This is partially due to the rough and unpredictable ocean conditions where these technologies have to operate. Meanwhile though, advances in ocean engineering have improved the technology for ocean energy conversion. Advances in some areas of the technology could achieve the goal of commercial power production by or even before 2010. (Lemonis 2004, 1)

Tidal energy generators are mainly divided into two categories: underwater turbines and hydrokinetic generators. Underwater turbines are simply freestanding turbines/propellors that can be grounded to the bottom of the ocean or the bottom of a tidal inlet. Hydrokinetic generators are more similar to existing hydroelectric power generation systems that are used in rivers throughout the world. However, rather than using a dam system or tidal barrage, which would create a structural barrier across a tidal inlet, hydrokinetic generators can be freestanding like the underwater turbines, and thereby are proven to have far fewer deleterious environmental impacts on marine ecosystems. (Perez, 2009, 2) The first bona-fide tidal energy plant was constructed in France, at La Rance in Brittany between 1961 and 1967. It consisted of a barrage across a tidal estuary that utilized the rise and fall in sea level induced by the tides to generate electricity from hydro turbines. (Bryden 2004, 142)

Wave power generators can be divided into four main technologies: Point absorbers, attenuators, terminator devices and overtopping devices. The most ideal conditions for wave power plants are in the Pacific Northwest. To date several international and domestic companies have filed applications with the Federal Energy Regulation Commission (FERC) for test projects off the coasts of California, Oregon and Washington. (Perez 2009, 3)

Internationally, wave power generators have received strong government support in Europe and Australia. Portugal is home to one of the first grid-connected, wave-power conversion farms, which began operation in September 2008. The technology used is an attenuator generator, which resembles linked sausages that float on top of the water and generate electricity by harnessing the power in the oscillation of the waves. (Perez 2009, 3) The same technology is being considered for test sites in Scotland, Hawaii, Oregon, California and Maine. A company called Energetech has been testing a full-scale, 500kW terminator device, which is “an oscillating water column (OWC) used in onshore or near-shore structures,” at Port Kembla, Australia and is developing another OWC project for Rhode Island. (Perez 2009, 4) In Wales, an overtopping device called the Wave Dragon is being tested for full-scale deployment. The overtopping device works by channeling waves into a reservoir structure that sits higher than the surrounding ocean; the water in the reservoir is released through turbines that generate electricity. (Perez 2009, 5) There are many different designs for wave energy conversion technology, even when compared with other alternative energy technologies. More than 1000 wave energy conversion techniques are patented worldwide. (Lemonis 2004,387 - 388)

Currently there are no tidal or wave grid-connected, full-scale commercial power plants in the US, and due to market concerns and regulatory agencies competing over jurisdiction of the US Outer Continental Shelf, it is expected that a working plant will not be feasible until 2020. Meanwhile in April 2009, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) signed an agreement to remove the regulatory barriers for hydrokinectic (ocean energy) development on the US Outer Continental Shelf, which opens the door for new developments. (Perez 2009, 10) In 2007 and 2008 FERC started to expedite permits for ocean energy projects and 2007 saw a marked increase in the number of permits for tidal energy projects.

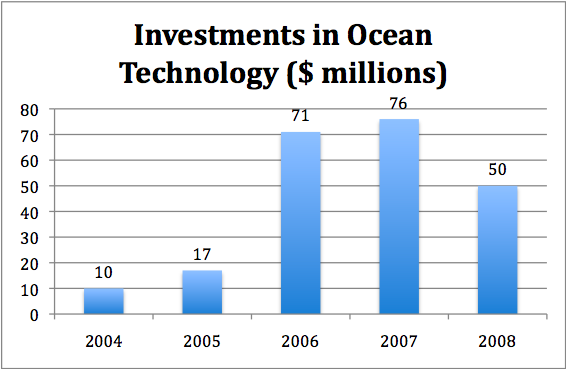

The market for ocean technologies started to grow in 2004 and maintained healthy growth though 2007 when the total investment in the technologies including both public and private sources, was $76 million. In 2008 the investments dropped by $26 million. (Perez 2009, 7) Figure 4 shows the evolution of investment in the technology from 2004 onward. The future promise of tidal/wave technology is great both in terms of total amounts of energy that can be generated, and the predicted cost-competitiveness of the technologies.

Figure 4

Total public and private investment in ocean technologies ($ millions)

Source: (Perez 2009)

e. The Leading Companies in Wind, Solar, Tidal and Wave

(GRAPH/CHART COMING SOON)

| Wind Companies | 2008 Revenue | Headquarters | Primary Outputs |

| Vestas | â¬6.035 billion

|

Randers, Denmark | development, manufacturing, marketing and maintenance of wind power systems. |

| Clipper Windpower | ?

|

London, England | turbine manufacturing and wind project development company |

| GE Energy | US$ 182.515 billion

|

Atlanta, GA | Wind turbine suppliers. Over 10,000 worldwide wind turbine installations. |

| Suzlon | $2.8 billion

|

Randers, Denmark (moving to Aarhus, Denmark) | supplier of wind turbines |

| Gamesa | â¬3.274 billion (2007)

|

Navarra, Spain | The company participates in"promotion, construction and sale of solar and wind farms; engineering, design, manufacture and sale of wind generators; energy solutions" |

| Solar Companies | Revenue ($m) | Headquarters | Primary Outputs |

| SunPower | ?

|

San Jose, CA | designs, manufactures and markets high-performance solar electric power technologies. |

| First Solar | $638 million (2007)

|

Tempe, AZ | design and manufacture solar modules |

| SunTech | ?

|

Jiangsu Province, People's Republic of China | Wind turbine suppliers. Over 10,000 worldwide wind turbine installations. |

| Evergreen Solar | ?

|

Marlboro, MA | "develops, manufactures and markets solar power products" |

| Applied Materials | $9.734 Billion (2007)

|

Santa Clara, CA | provides Nanomanufacturing Technology solutions for the global semiconductor, flat panel display, solar and related industries |

| Tidal Companies | Revenue ($m) | Headquarters | Primary Outputs |

| Verdant Power | ?

|

New York, NY | designs, analyzes, develops for manufacture tidal electric power technologies. |

| Ocean Power Technologies, Inc | ?

|

Pennington, NJ | Company focuses on offshore wave power technology, specifically their PowerBuoy® system |

| Palamis | ?

|

Edinburgh, Scotland | Manufacturer of offshore wave power technology, specifically the Pelamis Wave Energy Converter. This is a relatively mature technology that is deployed for commercial power generation. |

| Wave Dragon ApS | ?

|

Copenhagen, Denmark | Tidal energy manufacturer producing a floating slack-moored energy converter of the overtopping type. |

| Hammerfest Strom | ?

|

Hammerfest, Norway | develops and manufacturers tidal power stations. |

f. The Maturity of Solar, Wind and Tidal/Wave Technologies

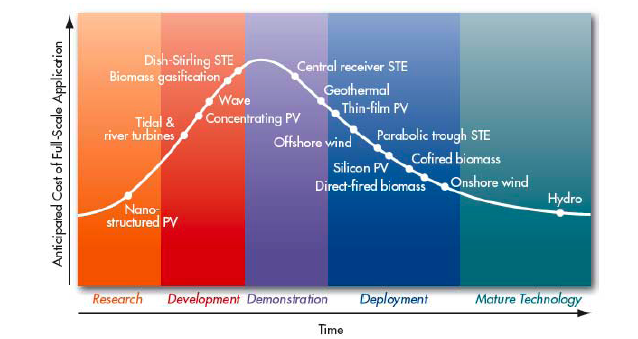

As mentioned above, each of these technologies is at a different stage of maturity, which influences its chances of commercialization, its cost of deployment, or - in the case of the most mature technologies - its market cost and the level of subsidies required to attain market competitiveness with incumbent energy technologies. In Figure 5 below, various alternative energy technologies are graphed on a time continuum, which maps the stages of technology development starting with basic research, moving to development, then demonstration, deployment and ultimately, maturity. The Y axis tracks the cost of the technologies showing that the research stage is typically a low cost, but the cost increases in the development stage and can peak between the development and demonstration phases, which then leads to a trip "down the hill" of decreasing costs as the technology approaches more far reaching deployment and maturity. (Lako 2008, 9) In economic terms this process can be referred to as reaching Economies of Scale, when the technology has a large enough market that the increasing deployment leads to reductions in the technology cost.

Figure 5

Stages of R&D, demonstration and commercialization of RE technologies

Sources: (Lako 2008, 9; EPRI 2007)

The graph demonstrates that tidal and wave technologies are still in the development stages, signaling both a high cost and a rising cost as they follow the curve towards demonstration. Further along the cost curve in the demonstration phase, central receiver STE, a version of concentrating solar power that uses tracking mirrors to concentrate the suns rays on a central heating tower, is at the highest cost point and just beginning move towards the deployment stage. Parabolic trough STE, a version of CSP that uses concave mirrors to heat pipes full of heat conducting liquid, thin-film PV, and silicon PV, round out solar technologies in the graph, and are all at various points in the deployment stage. Silicon PV is the furthest along in terms of affordable price, but in real terms it is still very expensive and requires generous subsidies to compete in the technology market. The final technology we are focusing our research on, wind, shows two vastly different costs for offshore and onshore deployed technology. Offshore wind is experiencing a growing market, but still suffers from high costs due to the shear size of the turbines - they are designed to produce up to 5MW per turbine and tend to be several hundred feet tall - the cost of designing turbines that can resist the increased pressures of high winds, rough water, and salt corrosion, and the difficult and costly underwater electrical transmission infrastructure - not to mention environmental permitting costs of offshore development. Additionally the difficulty of conducting regular maintenance raises costs as well. Onshore wind is the most competitively priced and most mature of the current alternative energy technologies. It is only eclipsed by hydropower, which has been used as a mainstream electricity source around the world for many years. Hydropower is not typically included in alternative energy technology growth studies due to its limited growth potential. There are very few river sites available, and in many cases rivers are experiencing reduced flows (in the US) and the required permitting to construct a dam is both complicated and expensive.

Concentrating solar power (CSP) technologies have been around for 25 years and measured approximately 400 MW of electrical capacity in 2008 with another 400 MW being built and 6GW in the planning stages. The market for CSP is being driven by government subsidies in Spain, the USA,and other countries. (Lako 2008) As mentioned above, parabolic trough and central receiver CSP technologies are on the path to maturity, though newer technologies referred to as solar dish and Fresnel-lens CSP, are less mature and are not noted in Figure 5.

Solar PV technologies are expensive as mentioned above, but they have benefited from generous subsidies in Germany, Spain, Japan and the US, which have greatly expanded their markets. The result has been a steady reduction in the cost of the technology. Developing economies like China and India are starting to build large PV manufacturing industries, which have similarly reduced the prices of PV panels. China's role in this growing market is explained in more detail in the Section 1.6.1 China's Market Share. While silicon PV panels are the most mature PV technology, new thin-film panels are coming down in price and beginning to benefit from increases in efficiency. Concentrating PV is another technology that is still in the development stages, but which shows great promise. (Lako 2008, 7)

Investments in on- and off-shore wind technology equaled ⬠27.5 Billion in 2007 and the technologies are considered mainstream. Know-how for onshore wind technology is more prevalent and has spread quickly, especially in Europe. Off-shore wind is experiencing growth in the UK, the USA, and South East Asia. Economies of scale have brought the price of wind technology down and onshore wind is approaching cost competitiveness incumbent fossil energy technologies. (Lako 2008, 7)

As discussed in the previous section 1.2.4 d Tidal/wave technologies, there is great potential for energy from the tides and waves, but currently, the technology is immature and will need time and development to enter the deployment stage and achieve economies of scale.

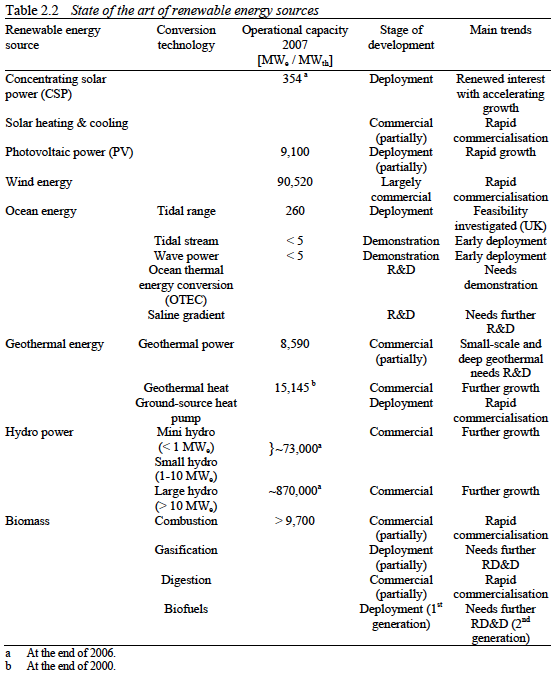

For detailed assessments of the development stages of these technologies, see Figure 6 below.

Figure 6

State of the art of RE sources

Source: (Lako 2008, 13)

There are many reasons why we are conducting this research, most notably, because climate change has the potential to be one of the most difficult and dangerous forces that humankind will face. By understanding the markets, technology development and forces that accelerate or slow innovation, we can learn more about which policies aid climate change mitigation efforts, and which do not. Wind and solar technologies in particular were chosen due to their potential for major reductions in global carbon emissions. In a 2004 article in Science Magazine that has become the canonical text in climate change mitigation efforts, Stephan Pacala and Robert Socolow of Princeton University, discussed the necessary steps that should be taken to meet the carbon mitigation goals set out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The article, entitled Stabilization Wedges: Solving the Climate Problem for the Next 50 Years with Current Technologies unveils a plan to reduce carbon emissions and stabilize them at less than half the pre-industrial level using a portfolio of technologies that are already available and at commercial stages. (Pacala & Socolow 2004, 1) Among these technologies are on- and off-shore wind, solar PV and solar CSP. Wind technology and solar technology represent 1 wedge each out of a total 7 wedges. A wedge is defined as equaling a reduction of one gigaton of carbon equivalent per year from 2004 (the year the article was published) until 2054. Under this model, wind technologies would have to grow by fifty times the capacity in 2004 or by 2 million 1MW peak windmills, and offset coal power by this amount. Paul Lako of the Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands, assess the current and future growth of wind energy in the US, EU and the rest of the world and determines that Pacala and Socolow's wind growth prediction is within the realm of possibility. (Lako 2008, 16) Lako conducts a similar study of the growth of solar power and determines that it is plausible that an increase of 2000GW of peak PV (or 700 times the solar capacity in 2004) could take place by 2054 as deemed necessary in the Pacala & Socolow report. (Lako 2008, 17) It is assumed that after 2054, the R&D investments taking place now will pay off in the form of commercial scale innovative technologies that can further reduce emissions.

The contributions of Software to Innovation in Alternative Energy Technologies

A Rapidly Growing Market

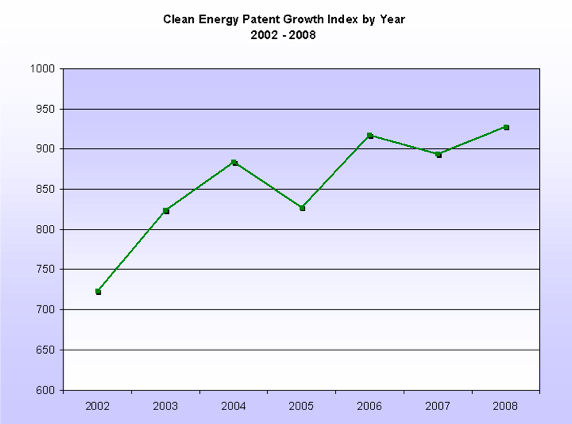

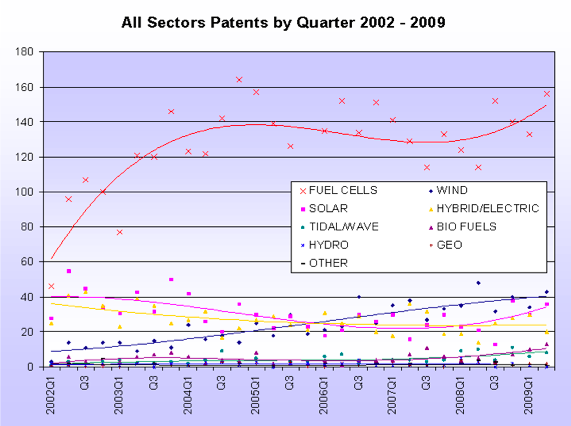

(A BOX SUMMARIZING THE BIGGEST COMPANIES, THEIR MARKET SHARE, TECHNOLOGICAL FOCUS AND POSSIBLE PATENTS WILL BE INSERTED - GREAT DIFFICULTY IN FINDING THE EXACT RELEVANT PATENTS...NO CLEAR INFORMATION ON THIS RATHER THAN THE GROWTH INDEX AND THE TECHNOLOGICAL ALTERNATIVES - based on this IP Profile of Biggest for-profit companies in AE)

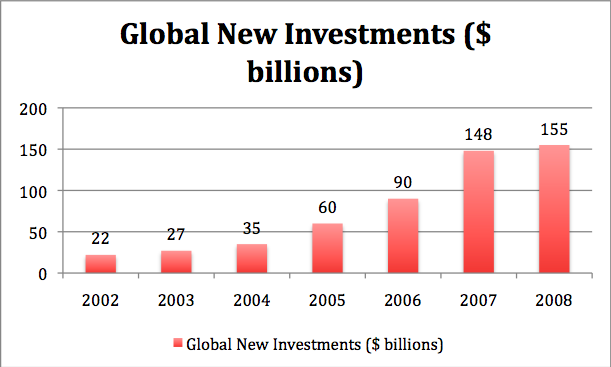

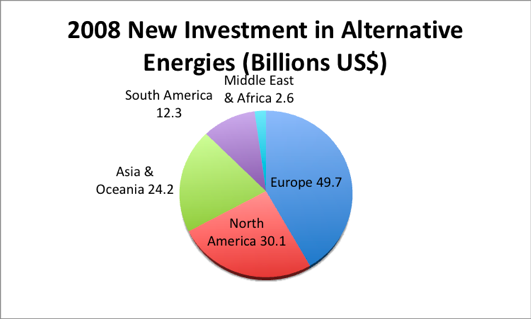

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and New Energy Finance, the cleantech industry grew to over $155 billion in 2008, up almost forty-eight percent from 2006, worldwide. (SEFIa 2009, 1) Figure 5 shows the gradual growth by financial quarter over the past few years. Its importance is not only environmental, but also geopolitical. The technologies that form alternative energy - and companies that explore them - vary immensely in type, innovation cycles, maturity and techno-economic readiness.

Figure 5

New global investments in clean technologies by year

Source: (SEFI 2009)

In terms of constituencies, the presence and influence of actors vary among countries, imprinting different forms to the organization of alternative energy innovation. For instance, in Japan, the government has traditionally taken a strong role in coordinating such activities through its Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry; while European countries have stressed and exemplified cross-country collaboration and coordination. In the US, the private sector exercises greater autonomy, even after the emphasis on public-private partnerships since the 1990s. In developing countries, such as Brazil, the government typically takes a very strong role in funding and coordinating innovation in energy, as in the biomass efforts of Petrobras. The various entities collaborate in a range of combinations, within countries and internationally, and impacts the availability of funding for R&D. For instance, the private sector accounts for the majority of expenditures for energy R&D in International Energy Agency (IEA) member countries, although governments account for a large fraction as well. (Gallagher et. al. 2006, 206)

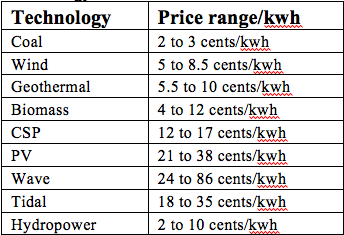

The global market for clean energy technologies relies on government support, which helps these technologies attain cost competitiveness with fossil fuel energy generation. Currently, as shown in Figure 6, the cost of generating electricity with alternative energy technologies is higher than with coal, which provides 50% of the electricity generated in the US and 80% of the electricity in China.[13] (Schell 2009, 1) Government support policies that subsidize the cost of deploying alternative energy technologies are referred to as demand-pull policies. The market leading companies, have generally developed in the areas of the world with the most generous demand-pull policies, and, predictably, under governments that have prioritized the growth of alternative energy technologies. The majority of the biggest and most successful wind and solar technology companies in the world are located outside of the US, with wind manufacturers being disproportionately grouped in Germany, Spain and Denmark, and solar companies being more widely distributed between Germany, Japan, China and the US. What distinguished these other countries from the US are their government's alternative energy policies. In Germany, Spain and Denmark a demand-pull policy called a Feed-in Tariff[14] (FiT) has been responsible for the rapid growth of their alternative energy technology markets, and has thus encouraged the development of many of the leading technology companies. (Rickerson & Grace 2007, 1) China, on the other hand, has taken advantage of the growing market for solar energy technologies, and has funded significant R&D to create cheap and efficient solar photovoltaic cells that are being sold in foreign markets, most notably the US and Europe. Only recently has China added its own FiT for wind and solar to help encourage their home market (Gipe(a) 2009, 1). Like most FiTs, China’s includes a “buy local” provision, which gives better financial incentives to those who install clean technology produced by Chinese companies. (Martinot & Junfeng 2008, 1)

Figure 6

The costs for generating one kilowatt hour with various types of electricity generation technology[15]

Sources: (U.S. DOEa 2008), [18]

(PARAGRAPH INTRODUCING NEXT SECTIONS ON COUNTRIES...AND WHY WE GO DEEP INTO USA AND CHINA)

The USA

The Market in the United States

The market for alternative energy technologies in the United States has grown due to a myriad of indirect and direct factors. Indirectly, global climate change concerns and volatile fossil fuel prices, along with US energy security concerns tied to its dependence on unstable foreign sources of oil, have pushed alternative energy into a strategic position of importance. Direct factors affecting the growth of the market have been a recent increase in private VC funding for alternative energy technologies, and a growing public-sector opinion that supporting these technologies is in the best interest of the country. In 2008, $19.3 billion of venture capital and private equity funds were invested in renewable energy and energy efficiency firms, an increase of 43% compared with 2007.[16] Up to this point, the US has lagged behind other countries, mainly those in Europe, in terms of its technology deployment funding (demand-pull policies). This has been due to complicated political and economic factors that have not plagued European nations to the same degree, which allowed policies that encourage the adoption of renewable energy to flourish. In terms of its public research and development (R&D) and demonstration funding (supply-push policies), the US reduced its investment in the 1980s - like many other developed countries - and has only recently begun to increase the funding for alternative energy and cleantech developments. (Gallagher et al. 2006)

The current market growth comes after a long lull that followed the original US push toward energy independence and alternative energy technologies in the 1970’s. The 1973 oil embargo caused the US and Europe to prioritize alternative energy investment and development, providing a buffer from the volatility of supply and demand for oil. The supply-push and demand-pull policies targeting alternative energy technologies, which were initiated during this period, defined the market leaders (Germany and Denmark) and those left behind (the US). Ultimately, the US was able to take a haphazard approach to alternative energy policies due to its prodigious stores of coal, oil and natural gas and political leadership that favored these industries. Now, spurred in part by the increasing momentum of the cleantech movement, alternative energy producers, consumers, and various regulatory and advocacy bodies are each responding to and evolving with the field, and thereby creating new market demands and offerings. While these trends are complicated in their economics, politics, and other social factors/barriers, the gradual consolidation of the field’s largest producers is already perceptible in the wind market, for instance. Figure 7 shows the distribution of the wind market by market share.

Figure 7

Top wind turbine manufacturers by market share

File:Windcompanies.pngâ

Source: (Efiong & Crispin 2007)

As noted in Figure 6, wind energy technology is the most cost competitive of the available alternative energy technologies, and has thus far been the most successfully and widely adopted technology in both the US and abroad. (REN21 2009, 8) In 2007 US wind power generation capacity grew by 45% with the installation of 5244MW of new wind turbines, which brought the total capacity in the US to 16,819 MW. This growth equaled one third of the new electricity generating capacity in the country that year, and established the US as one of the fastest growing wind markets in the world. As of 2008, the US became the fastest growing and largest wind market in the world following 2007 with another 8,351MW of new wind capacity to bring the country's total to 25,170MW edging out Germany (23,903MW) for first place. (WWEA 2008, 5) The US wind market was valued at $151.3 billion in 2008. (Bosik 2009, 1)

In 2008, the White House started to explore ways to support better development of wind energy innovations. They announced a memorandum of understanding for a two-year collaboration with six leading wind energy manufacturers - GE Energy, Siemens Power Generation, Vestas Wind Systems, Clipper Turbine Works, Suzlon Energy, and Gamesa Corporation. The agreement was designed to promote wind energy in the U.S. through advanced technology research and development, and siting strategies aimed to advance industrial wind power manufacturing capabilities.[19] The specific areas of research that will be addressed by the DOE and the collaborating companies are:

- 1) Turbine Reliability and Operability Research & Development to create more reliable components; improve turbine capacity factors; and reduce installation and operations and maintenance costs.

- 2) Siting Strategies to address environmental and technical issues like radar interference in a standardized framework based on industry best practices. Standards Development for turbine certification and universal generator interconnection.

- 3) Manufacturing advances in design, process automation and fabrication techniques to reduce product-to product variability and premature failure, while increasing the domestic manufacturing base.

- 4) Workforce development including the development, standardization and certification of wind energy curricula for mechanical and power systems engineers and community college training programs.

DOE Assistant Secretary Andy Karsner made the following announcement:

“The MOU between DOE and the six major turbine manufacturers demonstrates the shared commitment of the federal government and the private sector to create the roadmap necessary to achieve 20 percent wind energy by 2030. To dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions and enhance our energy security, clean power generation at the gigawatt-scale will be necessary to expand the domestic wind manufacturing base and streamline the permitting process.” [20]

Programs like this show that the US government is beginning to understand two of the major barriers to increased development of affordable and efficient clean technology. First, the historical failures of the DOE labs to understand the private sector and how to successfully launch technologies in the market, and second, the importance of collaboration and information sharing towards the development of better technologies.

While the US is making a late entry into the global clean energy market, it has had a successful start in terms of technology deployment as evidenced by their installations of wind turbines. The US has fallen behind in technology development though, and is left in a position of being dependent on foreign nations for technology licenses. So far the Obama Administration and the Secretary of Energy, Steven Chu - a Nobel Prize winning physicist and renewable energy advocate - have made favorable progress toward regaining the country's lead in energy technology innovation. President Obama said: “Our investments have declined as a share of our national income, (and) as a result, other countries are now beginning to pull ahead in the pursuit of this generation’s great discoveries.” (Belsie 2009, 1) In response the President has pledged to increase government R&D funding for new technologies, including alternative energy technologies, to over 3% of GDP, a higher percentage than the US reached at the peak of the Space Race in 1964. (Belsie 2009, 1)

A financial commitment of this level will be needed as the challenges of encouraging growth in the cleantech industry are unlike any of the US's previous technological challenges. No single clean technology will be sufficient to replace conventional carbon emitting energy sources as professors Pacala and Socolow have demonstrated through their study of stabilization wedges. (Pacala & Socolow 2004, 1) Clean technologies will require cost-effective development to succeed. Direct competition with the powerful coal, natural gas and oil industries and their lobbyists will make balancing government funding difficult because the government is simultaneously and extensively subsidizing both fossil fuels and clean technologies.

Alternative Energy Policies in the United States

The United States has a deeply politicized energy policy history. While the environmental wing of American politics, now tied to the political left, has urged subsidies to renewable energy - specifically to sun and wind - for decades, they neglected support for geothermal energy. The political right has meanwhile been just as enthusiastic in its support of subsidies to oil, natural gas, and nuclear energy. The coal and oil industries have been protected by the congressional delegations in key states where they provide employment. Due to these pressures, and a long regulatory history, the role of the government in the energy sector has been intense and interventionist. Even with the growing geopolitical and climate change realities, neither political party has attempted a balanced, technology-neutral approach to energy policy. Even today this legislative policy debate is missing in the U.S. Congress; each energy technology, both alternative and incumbent, seeks its own separate legislative deal for federal backing. (Weiss and Bonvillian 2009) This leads to the government picking technology winners, which is a policy destined for failure in the new energy future where a wide array of new technologies will be necessary to address the climate change issue.

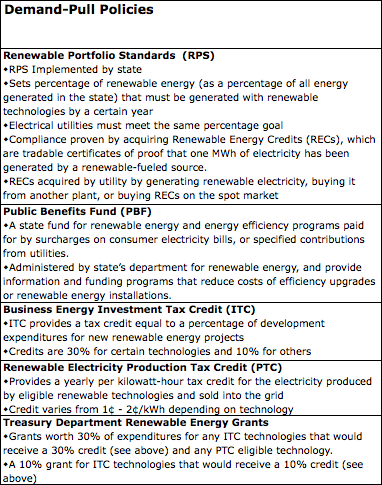

In the US, the first favorable government subsidy policy for alternative energy was introduced in 1978 - The Public Utilities Regulatory Policy Act (PURPA)[17] - which encouraged the installation of over 1400 MW of wind power capacity in California. (PURPA 2007; Gipe 1995) Most of the turbines installed were built in Denmark by the leading manufacturer at that time, Vestas, which is still the top manufacturer today. Figure 8 below shows other US demand-pull policies used to encourage deployment of alternative energy and clean technologies. Supply-push policies fall under the R&D investments in the US, and will be explained in the next section.

Figure 8

Demand-Pull technology deployment policies in the United States

Source: (DSIRE 2009)

Currently, the US is considering a carbon cap and trade bill, referred to as the Waxman - Markey Bill or the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009. [21] The idea behind a cap and trade bill is to assign an artificial price for carbon through tradable carbon credits. A carbon credit market introduces chances of profit for those who reduce their carbon emissions and have credits to sell, whereas those who don't reduce their carbon emissions will be forced to buy credits. The economic theory behind assigning a price to carbon is called internalizing externalities, or what some call "polluters pay." The theory refers to internalizing the cost of the environmental damage caused by incumbent fossil fuel sources (coal mining, oil drilling, carbon emissions, air-quality, water quality, general public health and climate change) into the price of power from those sources. This negates the need for subsidies to reduce the cost of alternative sources of energy by raising the cost of incumbent sources of energy and creating price parity. The other policy that can be used to achieve this is a carbon tax, which is a government regulated price on the cost of carbon emissions through a pollution tax. This model, while economically more efficient, is much less popular, especially among financial conservatives as it gives the government the power to choose a carbon price.

Renewable Energy Policies and Technology Innovation

While a response to the global threat of climate change requires an unprecedented response in terms of the large variety of GHG mitigation technologies and government policies to encourage the development and adoption of these technologies (Pacala and Socolow, 2006, 1), the necessary innovation to meet the challenge will not necessarily be met through the policies currently in use. There is an erroneous assumption among many stakeholders that policies that promote technology diffusion will also promote technology innovation. The way in which various energy policies affect the drive for higher efficiencies and energy outputs of myriad renewable energy technologies are the subject of heated debates. It is beyond the scope of this paper to analyze the full portfolio of energy policies being used around the globe to encourage renewable energy diffusion and, by some estimates, innovation, but a short discussion of the subject is necessary to frame the issue. As Nemet (Nemet 2006, 4) argued in a paper on demand-pull policies and the California wind energy market, when demand-pull policies are used to grow the market for a renewable energy technology through subsidies or other payments - “Increasing the expected profitability of investment in innovation may not provide sufficient incentives to induce efforts toward innovation.” His argument is that incentives for technology diffusion are not automatically synonymous with pushes for new efficiency innovations in the technology. The discussion can be simplified into a debate between two possible drivers of technology innovation - changes in market demand or advances in science and technology. (Nemet 2006, 5)

Advances in science and technology can determine the rate and direction of innovation, or so the argument goes. This is linked to the theory of Vannevar Bush (Bush 1945) referred to as the “post-war paradigm” in which the model of technology transfer was described as a progression from basic science to applied research to product development to commercial products. It was later theorized that this paradigm gained prominence in part due to the apparently strong correlation between R&D and innovation output. (Nemet 2006, 6) A principle argument against the theory was that it ignores the economic conditions, such as price, that can affect the profitability of technology innovations. Overall though, the theory stands that companies would need to invest in the science through R&D funding in order to have the knowledge to exploit opportunities emerging from the research. (Nemet 2006, 6)

The central discussion around the demand-pull innovation theory is that changes in the market demand create investment opportunities for firms to invest in innovation to meet new technology needs. Demand-pull energy technology policies are based on the idea that by subsidizing renewable energy technology and making these technologies competitive with the incumbent fossil fuels and nuclear energy sources, firms will be driven to innovate and create cheaper and better technologies to try and compete more effectively in the market. Other factors that can affect this demand-pull theory are the prices of fuel for energy plants, or the geographic variations in demand. In general, the argument against this theory is skepticism that firms can identify the technology needs from a fairly vast number of them, that their ability to then meet those specific needs with the existing technology abilities that the firms have is probably fairly limited, and that the firms will be unlikely to deviate from their existing R&D paths to fill a needed technology niche if it’s not a technology they have significant experience with. (Nemet 2006, 8)

There are ongoing debates about these two theories of innovation and how they interact. Many people have tackled the discussion. In some cases theories have developed around the idea that technology-push and demand-pull complement each other and innovation arises out of a complementary intersection of the two. In theory, certain market demands intersect with ongoing private technology pushes creating economic factors that accelerate the development of a particular developing technology. While there is still ample debate around this theory, a number of government supply-push and demand-pull policies have developed over the years in order to attempt to encourage innovation by reducing the cost to firms of producing innovations, and increasing the payoffs in the market for successful innovations. In the US, the political debates around the approval of these policies on state and federal level has led to continuous political wrangling. Despite the recognition that both of these policies are necessary to encourage innovation, especially in renewable energy technologies where barriers to profitable development are high, political debates continue.

In (Nemet 2006) exploration of the demand-pull policies, he uses a case study of the California wind market from the 1970’s through 1995. His study affirms that demand-pull policies increased the profitability of wind power and stimulated the diffusion of the technology, and that diffusion created opportunities for learning by doing. At the same time, his study found little evidence that the policies stimulated inventive activity. (Nemet 2006, 11,16)

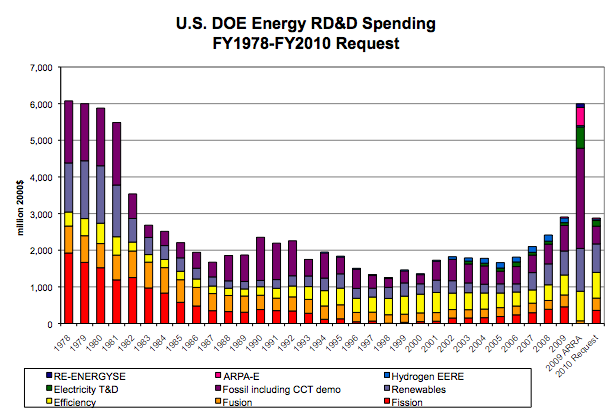

R&D Investment in the United States

As of 2007, federal support for energy R&D had fallen by more than half since a high point in 1978, and private-sector energy R&D has similarly fallen. (Gallagher, et. al. 2006) Since 2007, with the renewed interest in clean technologies and most recently, the economic meltdown and subsequent American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), which designated billions of dollars for energy R&D, the landscape has changed. Figure 9 shows the overall expenditures for US government energy research, development and deployment (RD&D). (Anadon et. al. 2009)

US Department of Energy RD&D Spending 1978 - 2010 Request by expenditure type

Source: (Anadon et. al. 2008)

While the ARRA funds have raised R&D and demonstration funding back to its 1979 level, the FY2010 request drops back down to previous levels which compare poorly to other major federal R&D efforts that met challenges of similar magnitude: the Manhattan Project, the Apollo Project, the Carter-Reagan defense buildup, and the doubling of the budget of the National Institutes of Health. Advances in energy technology will not occur on the scale required without significantly increased investment by both government and business, and in the years after 2009, the challenge will be to find that money in the government’s coffers.

a. Public R&D Funding

( QUESTIONNAIRE IS UNDER DEVELOPMENT TO SEND TO ALL CENTERS THAT RECEIVED FUNDS FROM THE CURRENT ADMINISTRATION TO MAP THEIR PATENT AND LICENSE PRACTICES)

( QUESTIONNAIRE WAS DEVELOPED AND SENT TO EFRC)

(TOP TEN US UNIVERSITIES FOR CLEANTECH: http://cleantech.com/news/5384/top-10-cleantech-universities-us)

Most of these funds are being given to the 17 U.S. Department of Energy laboratories, which have historically been an ineffective model for cleantech development and commercialization. The main reason for this ineffectiveness is that most of the labs do weapons research, which is developed for one guarantied client - the U.S. Government - and is considered a high priority given the size of U.S. military forces and their active involvement in two wars. Of the 12,400 PhD scientists employed in the DOE's labs, 5000 of them work at the top three weapons labs despite the US's shrinking arsenal, and far fewer PhD scientists work at the energy labs. The largest alternative energy lab, The National Renewable Energy Laboratory, employs 350 PhD scientists, and there is no system in the DOE that encourages collaboration between the public and private sectors. (Weiss & Bonvillian 2009, 152 - 153) As a result the lab system knows how to develop products for the military, but as a whole, lacks the experience and private sector business acumen to launch energy technologies from initial innovation through demonstration across the “valley of death”[18] and into commercialization. (Weiss & Bonvillian 2009, 31)

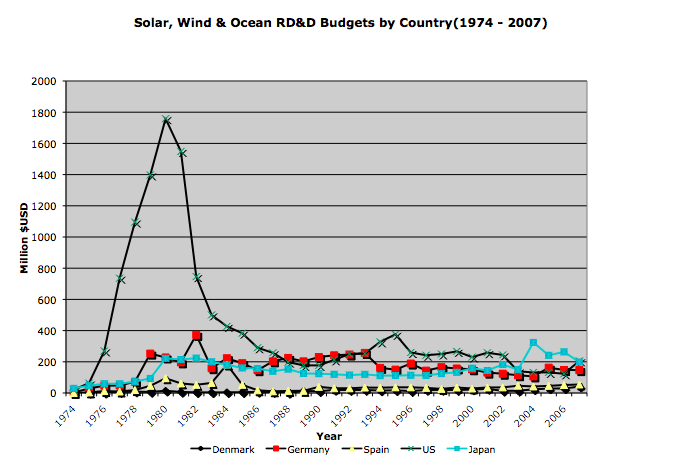

While energy technology innovation experts often note that it will take an R&D effort similar to historical US technology pushes like the Manhattan Project or the Apollo Project, this challenge differs fundamentally. The former projects had sole technological outputs and the government was the only user of that output. There wasn't a private market involved and the funding for the projects was unlimited. (Ogden et. al. 2008) In contrast, the current energy technology push requires a more logically designed innovation system that brings the publicly funded R&D labs closer to the private sector and the private market to ensure an effective technology transfer of multiple technologies. The recent release of ARRA funding has increased the US energy R&D funding a great deal as noted in Figure 9 above, but sound policies that avoid selecting technology winners and encourage all promising technology development, must follow. Figure 10 shows the historic investment in R&D for wind, solar and ocean technologies, and gives a clear indication that funding has stagnated since the 1970s allowing countries like Japan and China to make significant inroads in alternative energy and cleantech development. In tandem with this funding reduction has been an ineffective patchwork of energy policies that lack fundamental stability and consistency. (Weiss & Bonvillian 2009) Other issues that have plagued the US DOE lab system, have been a tendency for individual technologies' R&D funding to fluctuate significantly. It has been observed by researchers at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government that between 1978 and 2009 the average standard deviation of the variation across six fossil energy and energy efficiency technology areas was 27% meaning that there was a one in three chance that a particular technology area's funding would increase or decrease by more than 27%. (Narayanamurti et. al. 2009, 8) Additionally, over the years funding to the labs has changed to involve more small grants to individual investigators for basic research, rather than large project investments. This model is effective for universities, but tends to be ineffective when trying to integrate basic and applied science. (Narayanamurti et. al. 2009, 9)

Figure 10

Source: Authors illustration with data from (IEA 2009)

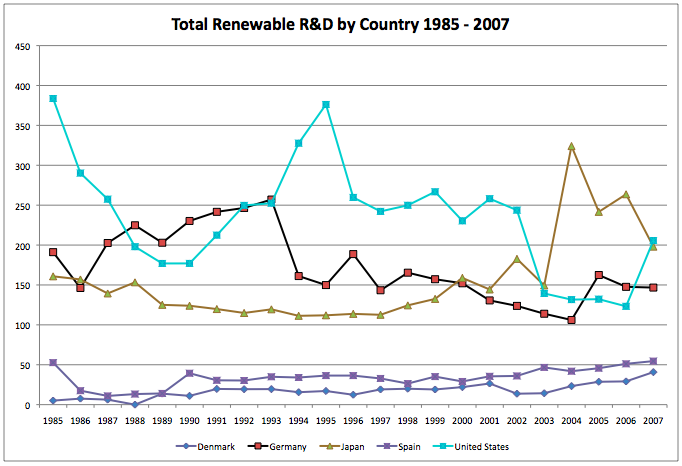

The same graph, limited to data from 1985 to 2007, is displayed in Figure 11.

Figure 11

Source: Authors illustration with data from (IEA 2009)

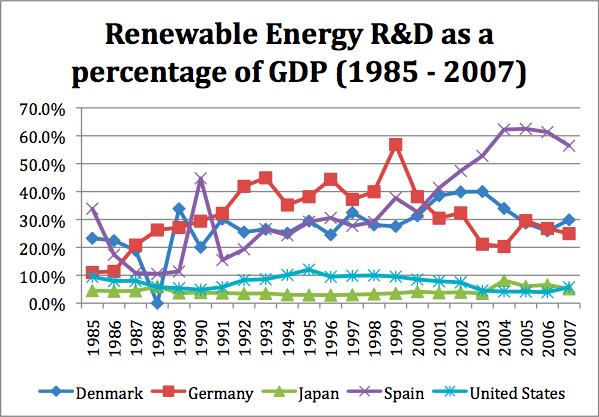

In Figure 12 the R&D spending on solar, wind and ocean energy technologies is displayed as a percentage of each country’s GDP. Given the overall size of the United States and Japan’s GDP’s it is not surprising that alternative energy technology is such a small percentage. Alternative energy technologies form a much larger percentage of Denmark, Germany and Spain’s GDP.

Figure 12

Source: Authors illustration with data from (IEA 2009)

It is apparent that the investment level of the ARRA funds in 2009 will need to be sustained for more than a year to provide the type of funding that will be needed for this clean technology revolution. These graphs show that allowing the R&D funding to drop back to the levels it has been at for the past 25 years will result in the stagnant development we have seen over that period.

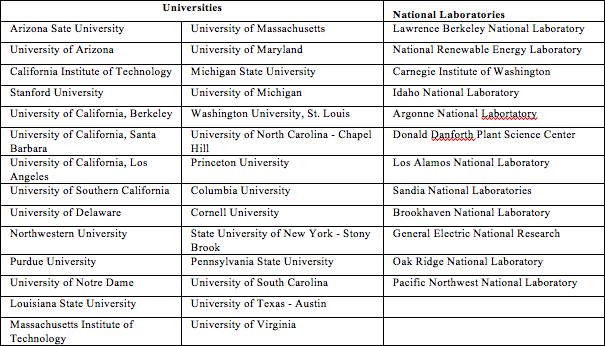

Another portion of public R&D funding goes to universities. The US Department of Energy funds 46 research centers through its EFRC Energy Frontier Research Centers (EFRCs), which are designed to address energy and science “grand challenges.” The 46 EFRCs are to be funded at $2 - $5 million a year for 5 years, and were chosen from over 260 applicant institutions. In total the program represents $777 million in DOE funding over five years, and 31 of the centers are led by Universities. In August, Secretary Chu announced the selection of the new EFRC centers and said:

Meeting the challenge to reduce our dependence on imported oil and curtail greenhouse gas emissions will require significant scientific advances. These centers will mobilize the enormous talents and skills of our nation’s scientific workforce in pursuit of the breakthroughs that are essential to expand the use of clean and renewable energy.

Figure 13 shows the 46 EFRC centers.

Figure 13

Source: (EFRC 2009)

Each institution received funding for a particular center doing research on a particular type of clean technology, and in some cases more than one center at a particular institution was awarded funding, as is the case with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), which receive EFRC funding for the Solid-State Solarthermal Energy Conversion Center, and American Reinvestment and Recovery Act of 2009 (ARRA) funding for the Center for Excitonics, which is also conducting research into solar PV technology. The EFRC represents an increased emphasis on the importance of university based research, and expands the R&D funding for this research.

The newest edition to the government's energy technology innovation efforts is a program sponsored by the DOE's Advanced Research Project Agency called ARPA-E. It has been modeled after the US Department of Defense's successful DARPA program, which funds research in defense technology [22]. ARPA-E is handing out $151 million to 37 energy projects that it has termed bold and transformational. (Madrigal 2009) The DOE noted that:

The grants will go to projects with lead researchers in 17 states. Of the lead recipients, 43% are small businesses, 35% are educational institutions, and 19% are large corporations. In supporting these teams, ARPA-E seeks to bring together America's brightest energy innovators to pioneer a low cost, secure, and low carbon energy future for the nation. [23]

The program has proven to be extremely selective given that of the applicants, 99% received letters of denial for their funding request. This exemplifies the financial risk factor of the program's stated goal "to overcome the long-term and high-risk technological barriers in the development of energy technologies." [24]

b. Private R&D Funding

Private investment in R&D for alternative energy technologies to replace the incumbent fossil fuel technology has been discouraged by the history of wild oscillations in the price of energy. In relation to transportation related alternative energy technologies, oil has been particularly volatile over the past two years during which time it rose to over $140 a barrel, then dropped precipitously, and has since begun to rise again. These peaks and valleys make private investors ambivalent about investing in alternative energy technologies because only sustained high prices for oil will provide the appropriate economic climate in which alternative energies can be profitable. Research has shown though that the rising prices for oil are tied to increased demand from developed and emerging economies, which, if sustained, could change the private investment climate for new technologies in the future. (Weiss & Bonvillian 2009, 7)

Based on a study conducted by the National Research Council in 2001, it has been estimated that between 1978 and 1999 almost two thirds of the total energy R&D expenditures in the United States were made by industry. (Comm. on Benefits of DOE 2001; Gallagher et al. 2006, 216) Due to this research and the assessments of experts at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, it is believed that the private sector provides a larger portion of the R&D funding for clean technologies. A more detailed assessment of this estimate is very difficult to accomplish due to the proprietary nature of the funding information within private companies. (Gallagher et al. 2006, 216) The access to information is limited starting from early stage angel investing and continuing through mature venture capital contributions, though, as detailed in the numbers above, there are market reports that quantify the venture capital and private equity portions of private sector investment. (can we check how much cias are investing? For example X % to R&Dâ¦even if it is not clear what “R&D” they are doing? Maybe in the market reports? We should try to interview people ate cias urgently)