Educational Materials/Paper

Increasing Participation and Decreasing Regulation in the Educational Materials Industry

(A Summary Paper of our Research to date)

By Carolina Rossini and Erhardt Graeff

Last Draft: December 8, 2009

Introduction

Over the course of twentieth century, the American textbook market evolved into the proprietary domain of large and multinational publishing houses. Only in the past few years have online collaboration and digital publishing lowered the costs of production and allowed for new entrants in the educational materials (EM) field. Thus far, however, new forms of EM have not had a disruptive effect on the traditional textbook market.

Advances in internet technologies and print-on-demand services have coincided with consumer advocacy campaigns and budgetary realities pushing the political climate to be more amenable to seeking alternatives to the traditional copyrighted and expensively bound textbook. A consensus has started to form that the traditional textbook is a broken model. Open Educational Resources (OER) offer a free content alternative, and new business models have emerged attempting sell the service of EM provision atop free content. This paper discusses the evolving political economy of EM in the US and offers a set of observations and preliminary recommendations regarding current barriers to peer production and open access of EM designed for the K-12 and Higher Education levels. In particular, our analysis looks at current OER and for-profit models and their potential for expansion and sustainability.

Description of the EM Market

Defining Educational Materials

The field of educational materials (EM) refers to a subset of the book, games, Internet, and software publishing industries that is focused on providing resources to a variety of educational market segments. For instance, PricewaterhouseCoopers characterizes the EM sector as divided into digital and non-digital solutions (Cola, et al. 2009). At the K-12 educational level, digital solutions include a range of technologies used to enhance the delivery and the administration of K-12 education, including data management systems, web-based course and assessment materials, and online tutoring and professional developmentâhowever, we will only focus on those digital solutions products that have specific educational purposes and where knowledge is embedded in a form that can be enclosed by some form of intellectual property. Regarding non-digital solutions, we include textbooks, course packs and other supplementary materials, and various educative toys and games.

Actors providing these materials are private companies such as publishers controlling the textbook and complementary materials markets; global media companies focused on the family-based market, such as the Discovery Channel; public institutions, such as National Public Radio; universities and their presses, providing both closed and open educational materials; and independent organizations and associations comprising educators and interested individuals wanting to contribute to the open educational resources (OER) movement.

"A significant feature of most educational resources is that they are restricted to many and can cost a lot to gain access to. This is largely because of a market economy around educational resources. They are copyrighted and packaged up as objectsâbooks, journals, videosâthat have to be bought from a store or accessed through course fees or university repositories (libraries in most cases). Even if this copyrighted material is available in public libraries, it is then effectively rationed by the numbers of copies available and the costs and opportunity costs involved in people traveling to the library to use them (with that use being further restricted by the all rights reserved copyright applied to them)." (Iiyoshi and Kumar 2008, 149)

Brief History of EM and Related Technology

- from History_of_EM_Field

Michael Watt has traced the history of US textbook publishing to the 1880s and ascribes the emergence of the textbook to “greater uniformity in local education systems resulting from immigration and industrialization” (Watt 2007, 9). For Watt, “the development of modern practices in textbook publishing in the USA was concomitant with the rise of mass education, characterized by graded organization of formal schooling into classes" (ibid., 4).

Established publishers quickly took control of and stabilized the new textbook market; and before World War I the American Book Company had formed a monopoly. New publishers proliferated after the war, and in 1931 the National Society for the Study of Education pushed for a standardized culture of publishers soliciting manuscripts and judging the innovative merit of each work and the competency of the respective authors.

During the 1950s and 60s, textbook publishing became more competitive but remained largely professional with companies led by founder-editors. The rise of the role of official state adoption, particularly of textbooks in each K-12 subject, coincided with this moment representing a new and important market force that heavily contributed to the sector structure we observe even today.

In the 1970s, what sociologists Patricia Thornton and William Ocasio call the "market logic" began to pervade the industry as investors became interested in the market potential of publishing houses (Thornton & Ocasio 1999). Many private companies went public and were purchased by investment companies, merged with other publishers, or similarly acquired. For instance, founder-editors, practitioners of an "editorial logic" focusing on reputation, were replaced by profit-maximizing chief executives (ibid.).

The market was further consolidated through the 1980s and 90s. K-12 business strategies for publishers focused largely on widespread state adoption of their textbooks. Leading textbook publishers with longstanding relationships at state and local levels began to include CDs and DVDs with their textbooks to deliver modular content, and many are now acquiring technologies that add value by incorporating assessment and analytical capabilities into instructional materials. Similarly, the strategy for Higher Education has moved toward bundling supplementary materials to cover all learning styles and satisfy a desire for multimedia components. The one-stop-shop strategy (including horizontal growth and product differentiation movements) in addition to resource modularity is becoming routine among the incumbents of the EM sector. However, the marketing approach continues to involve sales representatives approaching lecturers to individually adopt textbooks for their courses, particularly introductory, obligatory courses with large student enrollments.

Further growth in the demand for digital solutions has been caused by the ongoing impact of the No Child Left Behind Act, improving IT infrastructure in schools, and the growing number of tech-savvy students and teachers. In this market, acquisitions and mergers focusing on market penetration and product diversification seem to be the rule. Examples of this trend are Pearson's 2006 and 2007 acquisitions of eCollege, Effective Education Technologies, PowerSchool and Chancery (announced May 2006); McGraw-Hill's purchase of Turnleaf Solutions (announced in 2005), now part of The Grow Network; and Houghton Mifflin Riverdeep's purchase of Achievement Technologies.

However, PricewaterhouseCoopers identified a number of niche players focused on software development who have emerged alongside a “variety of small entities, many with roots in academia, [...] offering open-source instructional management systems to financially strapped school districts” (Cola et al. 2009, 2), as well as OERs. In addition, larger software/communications companies like Intel and Verizon are starting to offer free solutions through outreach programs in order to create goodwill and gain the opportunity to sell proprietary solutions.

Overview of IP Landscape

Copyright represents the most significant intellectual property tool involved in this field due to the textual nature of its outputs. Patents are also involved when factoring in the educational software segment; however, educational software represents a significant amount of copyrightable material as well. The use of strategies focused on copyright is one of the fundamental points on which ideological differences can be identified between private companies, the set of universities and independent organizations interested in OER, and the advocatory associations that represent each. Similar to the issues facing the newspaper industry, and by analogy the film and music industries, the protection afforded by copyright has become uncertain as EM goes digital and the ability to monetize digital distribution still presents a challenge and potential barrier to innovation.

An excellent introduction to the IP discussion surround EM is encapsulated in a quote from Iiyoshi and Kumar:

- "A significant feature of most educational resources is that they are restricted to many and can cost a lot to gain access to. This is largely because of a market economy around educational resources. They are copyrighted and packaged up as objects--books, journals, videos--that have to be bought from a store or accessed through course fees or university repositories (libraries in most cases). Even if this copyrighted material is available in public libraries, it is then effectively rationed by the numbers of copies available and the costs and opportunity costs involved in people traveling to the library to use them (with that use being further restricted by the all rights reserved copyright applied to them)." (2008, 149)

Our Research Questions

At the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard, we have been studying the US Educational Materials industry as part of a larger research project aimed at mapping models of knowledge flow and appropriation across a range of economic variables. Our goal is to understand how intellectual property and other factors affect the movement, utility, and usage of knowledge across a set of targeted industrial sectors. We are mapping the actors, trends, and activities around cooperation in each of these sectors to understand the broader forces motivating cooperation in general, but also the policies that came into places as forces shaping each of these spaces.

Our four general sectors are biotechnology, educational materials, alternative energy, and telecommunications. We are interested in the actors in these sectors, what models they choose to leverage in their knowledge work, and why and when commons-based models emerge and gain traction. The project is built on an analysis of a set of knowledge-intensive industrial sectors representing a gradient of knowledge appropriation styles ranging from significant commons adoption to negligible commons adoption, and focuses within each discipline on paradigmatic knowledge products for deeper analytics.

Sector analysis should provide us a powerful lens to examine a range of case studies and begin to develop theories about how, when, where, and why commons-based approaches develop, succeed, or fail in practice. For instance, in educational materials, we see enormous promise in collaborative knowledge generation for courseware and textbooks, but in alternative energy we find less evidence of spontaneous emergence of the commons.

The initial research questions that motivated this study are:

- How are components of the industrial structure changing in how they deal with and manage knowledge embedded assets, in different industries, different business models, and different sets of actors?

- How (and if) actors are incorporating commonsâbased strategies?

Thus, the Institutional Cooperation Project focuses on understanding how institutions shape the kind of organization available for sustainable human cooperation (social, economic and political behavior). As we are discussing in this paper, the educational materials industry and the emergence of OER present a key institutional example of commons-based activities evolving under dynamic economic and political circumstances.

Our Methodology

Literature Review

Key Interviews

Disruptive Innovation Framework

Forces affecting the EM Industry

Technological Innovations in EM

Consumer Advocacy Campaigns

Relevant Public Policy

State Textbook Adoption Policies

State adoption agencies (in Adoption States) and districts and their schools (in Open States) are the main customers of the K-12 publishing industry. States spend relatively little on K-12 textbooks: from a high of 2.3 percent of total education expenditures to a low of 0.5 percent, according to the Association of American Publishers’ school division (Whitman 2004, 6). On average, states spend 0.95 percent of their education budgets on textbooks--not quite a penny of every educational dollar.

A Dysfunctional System: The Textbook Adoption Process

The textbook adoption process, in place in at least twenty-one states, is a statewide process where a central textbook committee or the state department of education reviews textbooks according to state guidelines and either mandates which specific textbooks and educational materials that all public schools in a certain state must use, or distributes lists of approved textbooks and educational materials that these schools must choose from. Some of these states allow schools to buy other materials with non-state money. The states that do not hold adoption processes are called "Open States".

However, since publishers naturally want to make their textbooks available in as many schools as possible, amortizing their costs and keeping up with quarterly sales goals, the adoption states that regulate textbooks, effectively, determine their content nationwide. The most influential states are California, Texas, and, to a lesser extent, Florida, which account for up to a third of the nation's approximately $4.3 billion K-12 textbook market. According to The Thomas B. Fordham Institute, "Few el-hi textbook publishers can afford to spend millions of dollars developing a textbook series and not have it adopted in these high-volume states." (Whitman 2004, 19)

The Fordham Institute's report The Mad, Mad World of Textbook Adoption concludes that:

- "Textbook adoption has been hijacked by pressure groups;

- "Textbooks are now judged not by their style, content, or effectiveness, but by the way they live up to absurd sensitivity guidelines;

- "The adoption process encourages slipshod reviews of textbooks written by anonymous development houses, according to paint-by-numbers formulas";

- "Textbook adoption created a textbook cartel controlled by just a few companies." (Whitman 2004, I-II)

Textbook Adoption Review Practices

The Fordham Institute report offers a damning critique of the practice of textbook adoption review, suggesting that textbooks are rarely reviewed carefully but always scrutinized against "superficial 'checklist' criteria" (Whitman 2004, 24). Apparently, schoolbooks are never reviewed for their actual utility as education tools. Field testing is never required by the state (though textbook publishers do perform internal testing and focus groups for at least some textbooks).

- "The review process almost inevitably drives publishers and states to embrace the lowest common denominator in textbook content." (Whitman 2004, 24) "In practice, publishers typically stick the California and Texas charts together and produce textbooks that meet the many standards, criteria, and curricular goals of both states. As textbooks have to cover more and more topics, keywords, and the like, they end up jumping from subject to subject, covering little material in depth. Members of review committees and state boards are often not experts in any specific curricular area. Their suggested revisions rarely elevate the sophistication, scholarship, and literary quality of textbooks." (Whitman 2004, 28)

In Lies My Teacher Told Me, James Loewen's offers a similar account of state adoption review practices:

- State adoption "committees face a Herculean task [...] [i]n a single summer, [textbook reviewers] cannot even read all the books, let alone compare them meaningfully. [...] Since they have time only to flip through most books, they look for easy readability, newness, a stunning color cover, appealing design, color illustrations, and ancillaries such as audiovisual materials, ready-made teaching aids, and test questions. Ancillaries can be critical. Many teachers, especially those with little background, depend on them." (Loewen 1995, 308-309)

Consequences: A Conspiracy of Good Intentions

Since K-12 textbooks, generally, are not sold on the open market, market dynamics do not have the same effect on publishers as they do in higher education.

- "[I]n the K-12 textbook market, the customary feedback loop between manufacturer and user is missing. Former congresswoman Pat Schroeder, who until 2008 was the head of the Association of American Publishers, defended el-hi publishers in a television interview, pointing out that they are only following the time-honored business model, 'The customer is always right.'" (Whitman 2004, 30)

However, the problem with the K-12 textbook market is that the customers and buyers (i.e., the state adoption agencies) aren’t the actual consumers (i.e., teachers and students). In higher education the main problem is textbook price, but in K-12 it's textbook quality.

Because publishers are overly concerned with passing adoption standards, "hack writers from 'development houses,' known as 'chop shops'", author K-12 textbooks, anticipating objections from the big three states, effectively self-censoring content. But this standards-passing textbooks have not shown to be particularly effective for learning.

- "[T]extbook content in different nations correlated closely to what their children learned--and how they fared on tests. U.S. math and science textbooks were hundreds of pages longer than those in other lands. But they were so dumbed down, and flitted so relentlessly from topic to topic, that American schoolchildren were learning less than their peers." (Whitman 2004, 2)

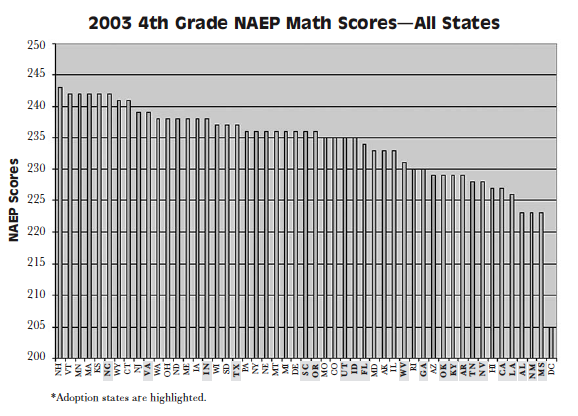

This chart on 4th grade math scores--elaborated with data from the 2003 National Assessment of Educational Progress--shows better score achievement among the open states. The same situation happens in reading and math, and again in reading in the 8th grade. (Whitman 2004, 21) In fact, the consistently low achievement scores come predominantly from adoption states such as California, Nevada, Alabama, New Mexico, Mississippi, Louisiana, South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Arkansas, Florida, and Texas. Whereas open territory states such as Vermont, Massachusetts, Montana, Nebraska, Maine, Kansas, Missouri, and North Dakota score consistently higher (Whitman 2004, 20).

California's Open Textbook Initiative (2009)

On May 6, 2009, as a possible answer for state budget problems, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger announced a Free Digital Textbook Initiative to encourage the production of K-12 level math and science e-Textbooks as a cost-effective alternative to traditional textbooks (Office of the Governor, California 2009). The goal was to have these educational materials approved for instruction in Fall 2009. Twenty textbooks were submitted by nine publishers, 3 of whom are OER projects. CK-12 Foundation submitted eight textbooks, Curriki submitted two, and Connexions submitted one.

On August 11, 2009, California released a report documenting the results of reviews of each textbook's coverage of the state's content standards, coordinated by the California Learning Resource Network (California Dept. of Education 2009). CK-12, with its focus on state standards for its “Flexbooks”, met most content standards with only a few exceptions. However, the reviews did not cover California's “social standards” for textbooks under the state’s adoption process (Paul 2009). A note at the bottom of each page of the report explicitly reads: “Materials were not reviewed for alignment to California's social content review standards; inclusion in this report does not constitute endorsement by the State of California".

It appears that these non-mandated free e-Textbooks will be relegated to supplementary resource status for classrooms that have fully-approved, but possibly out-of-date textbooks already on the shelves of their math and science classrooms. It is unclear how this will save money. And the OER movement is careful to distinguish California's initiative--which will distribute copyrighted PDFs--with the open-source and commons-based licensed materials characteristic of OER.

Criticism of Gov. Schwarzenegger's initiative often takes issue with his money saving logic for deficit-laden California (Schwarzenegger 2009). Arguably, digital materials require a personal computer available to every student, an e-Book reader like Amazon's Kindle, or mass printing of each reading assignment by the schools themselves. In a recent NY Times article, Tim Ward, an assistant superintendent in California, says his school district cannot afford any of those options (Lewin 2009).

Additionally, what Schwarzenegger seems to not have captured is that OER is a reaction to the move of proprietary, analog educational materials management onto the network. OER encourages and enables the open production, sharing of, and access to educational content and resources. This alone is a valuable societal good, increasing the value of investments made in education. But OER creates the opportunity for a more fundamental and transformative change: the move from passive consumption of educational resources to the formal engagement of educators and learners in the creative process of education content development itself. Thus, the core benefits of OER should probably not be conflated with cutting the costs of materials.

Current U.S. Dept. of Education Senior Advisor Hal Plotkin says he deserves some of the blame for the dependency on cost as the key argument. In 1998, when he first started advocating for innovative uses of digital technology in higher education, "cost" was the only demonstrable argument (Plotkin 1998). Only later did he observe how the development of what he originally called "public domain learning materials" was "also about improving the quality of teaching and learning through resource-sharing, collaboration and the more rapid transfer of educational best practices" (Plotkin 2007).

It was this realization that led Plotkin to campaign for Trustee position on the Board of Foothill-De Anza Community College District (FDHA) in 2003. During the first year of his trusteeship, he drafted and campaigned again, within FDHA, to enact the first college-wide policy offering institutional support to faculty pursuing development or adoption of OER (Plotkin 2004).

The enactment of that policy in 2004 laid the foundation for his testimony alongside Martha Kanter, Chancellor of FDHA, to the California Assembly Committee on Education entitled "Creating 21st Century Community College Courses: Building Free Public Domain Textbooks for Students", which in turn influenced California Assemblyman Ira Ruskin's Assembly Bill 577 to establish an OER Center at FDHA (Plotkin 2007).

Ironically, Gov. Schwarzenegger and legislators drafted a counter bill that expressly prohibited state funds from being used on OER projects for several years. Plotkin and Kanter lobbied against the bill with the support of Ruskin, and managed to renegotiate the language so that the funding moratorium was reduced to only 2 years and schools like FDHA were permitted to pursue OER adoption with other funding sources. FDHA soon applied for and eventually won a grant from the Hewlett Foundation to establish the Community College Consortium for Open Educational Resources (CCCOER).

Although the progress has not followed a straight path, California--in the same way it leads the U.S. on environment policies--so too seems to be a site for early innovation on OER adoption. Fortunately, OER's political incubation period appears to have been shortened with the election of President Obama--headhunting the leading minds in all policy areas. He recently recruited two of the aforementioned architects of OER adoption policy in California to the U.S. Department of Education, Kanter as Under Secretary, and Plotkin as a Senior Advisor.

American Graduation Initiative (2009)

The result of the Plotkin and Kanter's appointments was quickly realized in Obama's July 14, 2009 announcement of the American Graduation Initiative, which includes a proposal to allocate $500 million in competitive grants for developing "new open online courses" for U.S. community colleges (Park 2009).

Kanter and Plotkin's hopes for the FDHA-based OER Center was to ensure that there was a state mandate to investigate more cost-effective, and otherwise rewarding, means to developing high-quality, standardized educational materials. A important benchmark for OER is achieving the "required textbook" standard, so that OER-based courses qualify for credit transfer. Students spending two years at a community college then two years at a traditional four-year institution rely on these standardized exchanges to achieve their bachelor's degree; and often they struggle to afford textbooks on top of their tuition costs.

This is the central goal of the American Graduation Initiative's $500 million investment in open-source online courses. Plotkin says that although for-profit organizations will be on equal standing with non-profit/academic applicants, the competitive grants will encourage similar consortia poised to take advantage of Obama's call for hosting these new courses at individual institutions and distributing the resources under Creative Commons licenses (Plotkin 2009). An additional stipulation will require that all OER products be compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which addresses an issue that has been, according to Plotkin, “regrettably” overlooked by the majority of OER projects (Plotkin 2009). Non-ADA compliance currently represents a barrier to OER adoption, as schools fear law suits regarding disabled students' limited access to any common educational resources. Plotkin believes this will lead to even better OER output, in the same way that closed captioning has enabled search for video.

State Policies on Textbooks for Higher Education

Important groundwork for the American Graduation Initiative was earlier laid by the lobbying efforts of the Student PIRGs and the Make Textbooks Affordable campaign. Since their original Rip-off 101 report was published in January 2004 (Fairchild 2004), many states have adopted legislation regulating the process by which publishers sell textbooks to state universities. An index of relevant state legislation up to 2007 was compiled for a U.S. Department of Education study (ACSFA 2007). The legislation addressed nine central policy themes:

- Sales tax exemption for textbooks (including income tax credits for EM purchases)

- Require faculty to consider costs of educational materials

- Regulate educational materials that have particularly limited re-usability

- Require publishers and/or bookstores to offer unbundled textbooks in addition to bundles for particular courses

- Require publishers to disclose info on textbooks’ wholesale prices and revision histories (reduces sales of new textbooks by publishers)

- Recommend that institutions explore alternative textbook sources or otherwise innovate to reduce costs of educational materials (often textbook rental programs)

- Regulate textbook prices in public institutions

- Commission studies and reports to investigate high cost of textbooks

- Require schools/bookstores to actively promote textbook buyback programs (creating used book competition for publishers)

One excellent example of such legislation is California AB 2477, signed into law on September 16, 2004. The bill encouraged publishers to unbundle textbooks and reveal (to faculty): textbook prices, the differences between editions, and planned length of circulation of the current edition. Publishers should also try to update current editions with supplements rather than create new editions. Additionally, the bill requested the UC system (and required CSU and CCC systems) to encourage faculty to consider low cost textbooks, work with publishers to create cost-effective bundles, and inform students of textbook costs and differences between editions. Campus bookstores were then addressed, with the public university systems to evaluate the current system of communication between faculty and bookstores, while requiring campus bookstores to publicly list textbook costs for each course. (ACSFA 2007, 2)

Bills very similar to California AB 2477 (2004) were passed in subsequent years by Connecticut, Colorado, New York, Minnesota, Oregon, and Massachusetts.

Existing and Evolving EM and OER Models

Teacher-centric versus Student-centric

For-profit versus Non-profit

Hybrid Models

Discussion

Need for Open Access

Need for Participation

Significance of OER Movement

Conclusions

Bibliography

- ACSFA, 2007. Proposed and Passed State Legislation Pertaining to Textbook Affordability (2004-2007), Washington, DC: Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance. Available at: http://www.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/acsfa/edlite-txtbkstudy.html [Accessed March 12, 2009].

- California Department of Education, 2009. 'Free Digital Textbook Initiative Report', California Learning Resource Network. Available at: http://clrn.org/fdti/FDTI_Report.pdf [Accessed August 11, 2009].

- Cola, C. et al., 2009. Crossing the K-12 digital divide: Understanding and playing in a complex market. TS Insights, 5(1). Available at: http://www.pwc.com/extweb/pwcpublications.nsf/docid/51A2B147879DA97B852574400011BAAF [Accessed May 5, 2009].

- Fairchild, M., 2004. Rip-off 101: How The Current Practices Of The Textbook Industry Drive Up The Cost Of College Textbooks, Sacramento, CA: CALPIRG. Available at: http://www.maketextbooksaffordable.org/ripoff_2005.pdf [Accessed March 16, 2009].

- Iiyoshi, T. & Kumar, M.S.V., 2008. Opening Up Education: The Collective Advancement of Education through Open Technology, Open Content, and Open Knowledge, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lewin, T., 2009. In a Digital Future, Textbooks Are History. The New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/09/education/09textbook.html [Accessed August 10, 2009].

- Loewen, J.W., [1995] 2007. Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, Simon and Schuster.

- Office of the Governor, State of California, 2009. 'Gov. Schwarzenegger Launches First-in-Nation Initiative to Develop Free Digital Textbooks for High School Students'. Office of the Governor, State of California. Available at: http://gov.ca.gov/press-release/12225/ [Accessed December 7, 2009].

- Park, J., 2009. 'The American Graduation Initiative'. Creative Commons. Available at: http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/15818 [Accessed July 28, 2009].

- Paul, R., 2009. 'California open source digital textbook plan faces barriers'. Ars Technica. Available at: http://arstechnica.com/open-source/news/2009/05/california-launches-open-source-digital-textbook-initiative.ars [Accessed May 11, 2009].

- Plotkin, H., 1998. 'Tear Down The Walls / College in the Digital Age'. SFGate.com. Available at: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/g/a/1998/08/31/digitaleduc.DTL [Accessed August 12, 2009].

- Plotkin, H., 2004. 'Open Letter to Foothill-De Anza Faculty on Public Domain'. halplotkin.com. Available at: http://www.halplotkin.com/OpenLettertoFoothillDeAnzaFaculty.htm [Accessed December 7, 2009].

- Plotkin, H., 2007. 'News Flash: Ruskin's AB 577 Supports Open Education Resources'. What I Really Want to Say... Available at: http://www.plotkin.com/blog-archives/2007/03/news_flash_rusk_1.html [Accessed December 7, 2009].

- Plotkin, H., 2009 (August 10). Interviewed by: E. Graeff & C. Rossini. Available at: http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/commonsbasedresearch/Hal_Plotkin_Interview_Notes_-_August_10%2C_2009 [Accessed December 7, 2009].

- Schwarzenegger, A., 2009. 'Digital textbooks can save money, improve learning'. San Jose Mercury News. Available at: http://www.mercurynews.com/opinion/ci_12536333 [Accessed June 11, 2009].

- Thornton, P.H. & Ocasio, W., 1999. Institutional Logics and the Historical Contingency of Power in Organizations: Executive Succession in the Higher Education Publishing Industry, 1958â1990. American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 801-843.

- Watt, M.G., 2007. 'Research on the Textbook Publishing Industry in the United States of America'. IARTEM e-Journal, 1(1). Available at: http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=ED498713 [Accessed May 9, 2009]

- Whitman, D., 2004. The Mad, Mad World of Textbook Adoption, Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Available at: http://www.edexcellence.net/detail/news.cfm?news_id=335 [Accessed December 7, 2009].