| legal

theory: critical theory |

Feminist Legal Theories

|

|

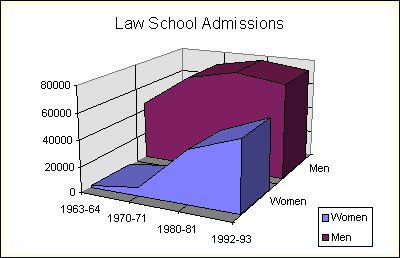

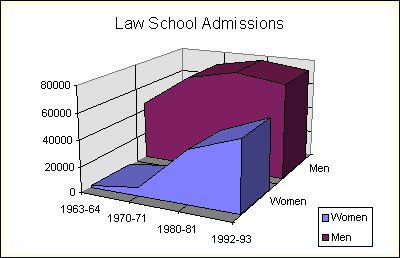

Starting in the 1970s, the enrollment of women in law schools changed from

a small number to a growing percentage, leaping from 6,682 out of a total of

78,018 law students in 1970-71 to 40,838 out of 119,501 in 1980-81. By the end

of the 1990s, women’s enrollments rivaled men’s. Women’s entry into the legal

profession both reflected and assisted the broad social movement for women’s

rights. During the 1970s, a few scholars  and

litigators started writing about women’s legal status and developed arguments

for equal treatment essentially framed on the theory that women should be treated

no differently from men. The leading figure in this effort was Ruth Bader Ginsburg,

a professor at Columbia law school who also directed the Women’s Rights Project

of the American Civil Liberties Union. She selected, argued, and won key Supreme

Court cases that effectively challenged explicit gender distinctions in the

law in a variety of contexts. (Reed v. Reed, 404

U.S. 71 (1971); Frontiero v. Richardson, 411

U.S. 677 (1973); Kahn v. Shevin, 416

U.S. 351 (1974)) The winning strategy sought equal treatment by targeting

chiefly instances where a gender-based distinction could be seen to advantage

women and disadvantage men.

and

litigators started writing about women’s legal status and developed arguments

for equal treatment essentially framed on the theory that women should be treated

no differently from men. The leading figure in this effort was Ruth Bader Ginsburg,

a professor at Columbia law school who also directed the Women’s Rights Project

of the American Civil Liberties Union. She selected, argued, and won key Supreme

Court cases that effectively challenged explicit gender distinctions in the

law in a variety of contexts. (Reed v. Reed, 404

U.S. 71 (1971); Frontiero v. Richardson, 411

U.S. 677 (1973); Kahn v. Shevin, 416

U.S. 351 (1974)) The winning strategy sought equal treatment by targeting

chiefly instances where a gender-based distinction could be seen to advantage

women and disadvantage men.

In 1979, Catharine MacKinnon wrote a book taking a different approach. In

Sexual Harassment of Working Women, she advanced a legal theory designed

from the standpoint of women and intended to resist patriarchal hierarchies

in social relationships. MacKinnon argued that injustices experienced by women

flowed not mainly from gender-based distinctions in the law, but from subordination

to men in society and its parallel legal culture of patriarchy. For example,

a man may think his behaviors toward women at work are affectionate or friendly

or fun while his female coworkers experience his conduct as hateful, dangerous,

and damaging. These perceptions by women, MacKinnon maintained, are not idiosyncratic

but widespread, and reflect what the law should recognize as sex discrimination,

requiring punishment and deterrence. Often called the dominance approach, MacKinnon’s

ideas influenced many others who developed critiques of the formal, equal treatment

approach to the issue of gender equality. She developed her theory further in

works on pornography, rape, and legal theory.

By the early 1980’s, some legal scholars who identified as feminists became

attracted to critical legal scholarship, even while faulting it for neglecting

women and their experiences and viewpoints. Like feminists in other fields,

feminist legal scholars emphasized the importance of lived experience and actual

dialogue, often in collective consciousness-raising settings, as a basis for

critical knowledge. Feminist legal scholars themselves often write from personal

experience and report the personal experiences of others. Feminist lawyers also

introduced briefs into courts that collected women’s stories. One

brief collected many women’s accounts of their reasons for seeking an abortion,

and thereby brought to the judges’ attention the contexts of those decisions

which otherwise risked treatment solely in abstract terms. Relaying and analyzing

women’s experiences, feminist scholars critiqued gender hierarchies and sexual

stereotypes. In addition, some feminists began to enlist critical techniques,

including deconstruction and post-modern readings, to expose internal inconsistencies

within seemingly coherent legal concepts. Some drew analogies to workers’ unequal

bargaining power in the workplace to women’s situations as wives and homemakers.

Others borrowed directly from the civil rights movement to analogize discrimination

on the basis of race to discrimination on the basis of sex while still others

turned to emerging work in psychology and moral theory to advance legal arguments

on behalf of women.

Three kinds of feminist legal scholarship inspired and evaluated parallel

advocacy on behalf of women in courts and legislatures. [9] The earliest work

articulated women’s claims to be granted the same rights and privileges as men,

and used the strategy of challenging any gender distinctions to push toward

this end. Ending the exclusion of women from particular opportunities for paid

employment and advancing women’s participation in politics, juries, commerce,

and positions of authority and trust became central to this equal treatment

effort.

[9] The earliest work

articulated women’s claims to be granted the same rights and privileges as men,

and used the strategy of challenging any gender distinctions to push toward

this end. Ending the exclusion of women from particular opportunities for paid

employment and advancing women’s participation in politics, juries, commerce,

and positions of authority and trust became central to this equal treatment

effort.

A second body of work advocated respect and accommodation for women’s historical

and ongoing differences from men. Here the central wrong to remedy was the systematic

undervalution or disregard for women’s historic and persistent interests, traits,

and needs. Legal scholars began to build upon Carol Gilligan’s influential book

in moral and psychological theory, In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory

and Women’s Development (Harvard University Press 1982) to support claims about

women’s special and valuable traits. Legal scholars joined with others to advocate

for pregnancy and maternity leaves for women in paid employment, for comparable

work compensation to elevate the remuneration and status of work traditionally

performed by women, and for special rights for women in response to rape, intimate

violence, and reproduction. Methodologically, this special treatment or cultural

feminist work often criticized the assumption of autonomy pervading Western

economic, social, and political theory and also criticized the preeminence of

marketplace values in an effort to elevate respect for human relationships and

noncommodified values.

A sharp tension emerged between the ideas of equal treatment and special treatment.

In dueling court briefs, op-eds, and law review articles, the advocates of both

positions engaged in a "sameness/different debate." If women needed

t be treated precisely the same as men, then law should not accommodate women

or offer rights unclaimed by men. Maternity leaves and protections for battered

women seemed to violate the equal treatment norm of gender neutrality. Yet gender

neutrality could often produce rules and practices making lives worse, not better,

for women.

A third group of scholars rejected the preoccupation with reconciling similarities

and differences between men and women. The sameness/difference debate seemed,

to them, to stem from the structures of law and society that used men as the

starting point for analysis. It is only an unstated male norm that makes maternity

leave seem to be special treatment for employees. The focus on similarities

and differences between men and women also failed to draw attention to the varieties

of women, who differ along the lines of race, ethnicity, disability, sexual

orientation, class, and religion, and other potential lines. Some in this third

group explicitly embrace postmodernist challenges to the very category of "woman."

It is a mistake, say these feminists, to treat women as all having the same

interests, identities, needs, and values, especially since doing so tends to

privilege the preferences and viewpoints of privileged white women. Instead,

feminist analysis should focus on the intersections of gender, race, class,

and sexual orientation and their treatment by law; or the gender performances

or the production of gender through cultural symbols and practices; or the on

multiple perspectives and social positions occupied by different women at the

same time and the same woman at different times. Others seek policies or modes

of analysis that use both men and women, of all kinds of background, as the

starting point of analysis, and design rules for workplaces, families, politics,

and society that are fully inclusive.

The different strands of feminist work join issue on the question of agency

and victimization. Equal treatment feminists emphasize that women should be

treated as choosers, capable of exercising free choice and living with the consequences

just like men. Special treatment feminists instead address the arenas in which

women face victimization and need special protections; a battered woman who

kills her batterer in his sleep needs a different kind of self-defense rule

than the one available to a man who could physically combat his aggressor. The

third group of feminists – some drawn to post-modernism, some seeking to resolve

the sameness/difference dilemma – search for alternative ways to understand

how women can be both free and constrained, victimized and choosing. For them,

just as it would be too limited to imagine that all women can choose as freely

as some privileged men can, it would be too constraining to imagine that all

women are victims and incapable of free choice. Some propose a notion of partial

agency, selective scope for autonomous choice, that deserves recognition even

as the structures curbing women’s choices warrant change.

Consider how these strands of feminist legal work apply to a particular case.

Many feminists have commented on the Supreme Court’s decision in Michael M.

v. Superior Court of Sonoma County (450

U.S. 464 (1981)) There, a teen-aged boy brought an Equal Protection

challenge to a California law punishing any male who had sexual intercourse

with a female under age 18, but not punishing a female who had sexual intercourse

with a male under 18. Most of the Supreme Court justices rejected the challenge

by reasoning that men and women are not similarly situated in the context of

sexual intercourse and child-bearing, and therefore a state could treat the

two groups differently. Deterring teen pregnancy supplied a sufficient rationale

for the law. Females have the deterrent of the risk of pregnancy; the criminal

penalty imposed solely on males "serves to roughly ‘equalize’ the deterrents

on the sexes," reasoned the Court’s plurality opinion. Although most feminists

criticized the opinion, its acknowledgment of the dangers of sexual aggression

to women and the special risks of pregnancy for women accorded with some features

of "difference" or cultural feminist analysis.

The dissenting justices in the case argued in contrast that distinguishing

males and females was not justified here; females too should face punishment

and that would further the state’s goal of deterring teen pregnancy. Feminist

scholars who pursue the equal treatment line of analysis aligned with the dissenters

in opposition to special treatment for females. Others agreed with the dissent

in hopes that an equal treatment approach would challenge the stereotypes of

males a sexual aggressors and females as passive victims that animated the plurality

opinion.

Rejecting both the plurality and dissenting views, Frances Olsen wrote an

analysis informed by critical legal studies and by the dominance approach

to gender issues. She started by identifying an irresolvable conflict at the

heart of the case between women’s needs to be free from sexual exploitation

and women’s needs to be free from sexual stereotypes and sexual restrictions.

Efforts to protect women simultaneously subjected them to state oppression;

efforts to resist state oppression exposed them to continuing risks of sexual

exploitation. Rights analysis could not resolve the problem because women should

have rights against sexual violence but also rights to pursue their own sexual

freedom.

Rather than asking which right deserved greater protection, Olsen urged a focus

on women’s empowerment, and recommended according to the minor woman control

over the prosecution decision. Then a young woman would be free to engage in

sexual activity or to accept the protection of the statutory rape laws. Alternatively,

she suggested  extending

the rape law to cover underage males as well, or to do so unless the two teen

sexual partners were close in age (and thus more likely engaged in consensual

activity). More important than her proposals, however, was her approach, which

emphasized the indeterminacy of rights and the search for reforms in light of

sociological, moral, and political commitments, and empowerment of individuals.

extending

the rape law to cover underage males as well, or to do so unless the two teen

sexual partners were close in age (and thus more likely engaged in consensual

activity). More important than her proposals, however, was her approach, which

emphasized the indeterminacy of rights and the search for reforms in light of

sociological, moral, and political commitments, and empowerment of individuals.

Feminists legal scholars often disagree about methods of analysis, tactics,

and whether to herald or castigate the results of particular controversies.

For example, feminist legal scholars take opposing positions on the regulation

of pornography. Some argue that pornography is a form of sexual discrimination

and that victims who are depicted in it or who are subjected to assaults influenced

by pornography should be able to bring civil actions when they can prove actual

harm. Others argue that legal intervention of this sort would create unwarranted

state restrictions on private liberty or fail to effectuate protections for

women. Feminists also disagree about the regulation of prostitution. Some argue

that the state should no longer ban prostitution which should be viewed as a

legitimate option for women seeking to earn a living. Others argue that prostitution

debases women and could only reflect such sharply limited choices as to render

meaningful consent unavailable.

Uniting feminist legal theorists are commitments to analyze law from the perspectives

of all women and to criticize law as a patriarchal institution that contributes

to the subordination of women. Feminists ask for the evaluation of legal doctrines,

particular cases, and legal institutions such as courts and law firms in terms

of their effects on women’s actual lives and interests. They urge greater legal

protections for reproductive freedom, parenting, and freedom from sexual exploitation.

They urge empowering women to make decisions in their own lives, including decisions

about how to resolve conflicts affecting them. They examine gender bias and

degradation of women even when it is not explicit: such as in the treatment

of poverty, the funding of medical research, the standards governing child abuse,

definitions of libel and slander. Asking the "woman question" leads

feminists to examine implicit invocations and reinscriptions of gender even

in places where it is not obviously addressed, as in the relationship between

federal and state courts, and the structure of the tax code. Feminist legal

scholars embrace calls for social change but some see law as a tool and others

see law as inextricable from the social constructions of gender and desire that

themselves need to be resisted.

Feminists have criticized legal education as unduly combative and competitive,

giving little room for the voices of women students. Feminist scholars have

turned empirical attention to law schools and report that women students often

feel silenced in classes due to ridicule by their classmates, intimation by

their professors, and priority placed on quick aggressive speech rather than

more thoughtful, collaborative discussions. Reform of these practices would

benefit many men who also feel shut out by law school classrooms.

Feminist legal scholars have pushed for changes in the law school curriculum

to include previously omitted subjects such as rape, intimate violence, and

sexual harassment; these are now standard subjects in criminal law and torts

courses. They have also produced scholarship identifying and challenging gender

biases in contract doctrines, employment law, tax laws, and property rules,

and developed notions of sexual dominance to strengthen claims for equality

in the contexts of sexuality, reproduction, pornography, and family law. They

urge inclusion of such approaches in law school instruction as well as in legal

advocacy. Similarly, feminist legal scholars argue for attention in legal education

and in legal advocacy to particular contexts. Situations generating conflicts

should be analyzed in light of larger patterns of political, economic, and social

inequalities along not only gender but also race, class, and sexual orientation

lines.

Opponents of feminist legal work themselves reflect varied positions. Some

share the vision of equality for women but object to the trends in feminist

legal scholarship toward emphasizing women’s victimization or toward the fluidity

and multiplicity of postmodernism. Others argue that the free market and libertarianism

offer the better avenues for gender equality than any explicit attention to

gender.

Another group of critics differ not on tactics for achieving gender equality

but rather object to the visions of equality they attribute to feminism. Some

complain that feminist legal scholars view all heterosexual intercourse as rape

and all sexual banter as harassment. Others view feminist legal arguments as

trivial or inconclusive, and reject particularly the use of narratives and contextual

stories as subjective and inadequately analytical. A few have criticized feminist’s

critiques of conventional for threatening to produce legal pedagogy that is

soft and insufficient to prepare students for the rigors of law practice. Others

draw on sociobiology to defend apparent gender inequalities in wages, employment,

and even male sexual freedom as products of nature.

and

litigators started writing about women’s legal status and developed arguments

for equal treatment essentially framed on the theory that women should be treated

no differently from men. The leading figure in this effort was Ruth Bader Ginsburg,

a professor at Columbia law school who also directed the Women’s Rights Project

of the American Civil Liberties Union. She selected, argued, and won key Supreme

Court cases that effectively challenged explicit gender distinctions in the

law in a variety of contexts. (Reed v. Reed, 404

U.S. 71 (1971); Frontiero v. Richardson, 411

U.S. 677 (1973); Kahn v. Shevin, 416

U.S. 351 (1974)) The winning strategy sought equal treatment by targeting

chiefly instances where a gender-based distinction could be seen to advantage

women and disadvantage men.

and

litigators started writing about women’s legal status and developed arguments

for equal treatment essentially framed on the theory that women should be treated

no differently from men. The leading figure in this effort was Ruth Bader Ginsburg,

a professor at Columbia law school who also directed the Women’s Rights Project

of the American Civil Liberties Union. She selected, argued, and won key Supreme

Court cases that effectively challenged explicit gender distinctions in the

law in a variety of contexts. (Reed v. Reed, 404

U.S. 71 (1971); Frontiero v. Richardson, 411

U.S. 677 (1973); Kahn v. Shevin, 416

U.S. 351 (1974)) The winning strategy sought equal treatment by targeting

chiefly instances where a gender-based distinction could be seen to advantage

women and disadvantage men.