Resources |

BOLD 2003: Development and the Internet

Module

I |

Module II |

Module III |

Module IV |

Module V |

Learning

by Colin Maclay and Charles Nesson

with Isabel Neto

Introduction

Case Studies

Discussion

Panel

Additional Resources

Additional Case Studies

The combination of advances in information technology and increasing perceptions of its importance in the modern economy has fostered significant interest on the part of both developing countries and development practitioners in leveraging information and communication technologies (ICTs) to improve learning opportunities. While information technologies have long been present in some educational settings, the massification of the Internet and World Wide Web, in conjunction with increasingly powerful and inexpensive technology have changed the level of promise associated with ICTs in this arena.

This module will attempt to offer a basic picture of the broad ICT and learning landscape, as well as complementary deeper consideration of select specific issues. We will examine different goals, strategies, and challenges, and prompt participants to explore the implications of our experiences to date.

The module begins with four short case studies, each followed by a series of questions designed to elicit debate about the broader meanings of certain aspects of the case. The second part of the module offers a series of topical articles that build on the cases indirectly, again followed by questions that should help draw connections among them. During the course of the week, we have also invited special guests who are intimately familiar with the case studies to participate in the dialogue, something of a virtual panel discussion (more details on this over the course of the week). The topics covered in this module are by no means exhaustive, and will not explicitly examine many important topics including broad educational reform efforts, distance education, capacity building, and technological tools.

Background

Governments, the private sector, international institutions and non-profits alike are promoting the use of computers and the Internet in the hopes that they may serve as transformative educational resources. Their goals are varied and cover virtually every challenge facing education systems. They include improving mastery of content (literacy, language, math and science), developing basic technological skills (programming, computer literacy), providing educational resources and content, supporting and supplementing educators (through training and distance education), fostering creative and team oriented skills (through project-based learning and group work), individualizing the learning experience, and, of course, enabling broad educational reform.

The implications, academic and otherwise, of the introduction of ICTs into schools are not yet clear on a widespread basis, largely due to the lack of rigorous analysis of these efforts and their relatively recent onset. Consideration of these topics leans heavily on anecdote and intuition, with few controlled experiments, and the limited data gathering common in many developing world nations. The varied goals and roles of technology make meaningful measurement hard, and accompanying interventions make ICT’s effects more difficult to isolate. As policymakers and educators move ahead, improving our analysis of ICTs and learning remains largely unaddressed.

Many agree that ICTs can act as a catalyst for education reform, attracting attention to education, injecting dynamic learning opportunities into the curriculum, and offering access to nearly limitless content (significant language barriers notwithstanding), but introducing technology without other components will leave these lofty aspirations beyond reach. Experience suggests that the challenge of integrating ICTs in learning is not as straightforward as it may appear.

While some smaller scale pilot projects to integrate technology into the educational process have shown promising results, many of the larger developing world initiatives continue to fall prey to age-old education and development challenges. Governments and educational institutions are wrestling with unanticipated institutional, financial, philosophical (of education) and political hurdles, and many are finding themselves under-equipped to deal with the challenges. To be sure, efforts to integrate ICT and learning are relatively young (more so in the developing world), and the challenges are complex ones. While the responses to these barriers are not yet clear, it is clear that needs, styles, challenges and goals vary widely among countries and communities.

What are some of the institutional barriers to integrating technology – and why might school administrators be resistant to it? How do we ensure that the projects we develop are financially sustainable? Should technology be focused upon as a subject or used as tool in different subjects? How do we handle the re-balancing that arises when these new tools and ideas enter the classroom and school, changing the way teachers and learners interact? How do we develop the right stimuli to get teachers, learners and community members interested and excited in participating? How do we ensure the survival of these programs and priorities over changes in governments?

These barriers do not fit neatly into clearly defined categories, tending to exist on a series of continua, but one way to describe the principal challenges is along the following lines:

Institutional – Capacity of schools, administrations, and implementing and supervisory authorities, as well as individual educators (particularly when they are often skeptical, afraid of losing their job, underpaid and undertrained) to undertake a wide variety of activities including teacher training and motivation, development and adaptation of curriculum to relevant standards, program evaluation, and maintenance of ICT tools.

Financial – Access to necessary funding, including not only the initial costs, but the oft-forgotten ongoing expenses of operations, including connectivity and electricity, plus maintenance, and equipment replacement, and the budget for initial and ongoing training (commonly recommended at 30-40% of overall project investment).

Philosophical (of education) – Agreement on a contextually relevant vision and approach for education reform that addresses key questions about goals and methods for learning (such as finding the balance between teacher-directed instruction, a project-based constructivist approach, or including project-based constructivist approaches within a standards-based curriculum).

Political – Delicate alignment of stakeholders that permits decision-makers and implementers (regardless of whether they are from government or other sectors) to address the aforementioned challenges effectively, in spite of changes in popular sentiment or power structures.

While technological areas are another major challenge and could well be another category, they already tend to gather an inordinate amount of focus, particularly in the planning stages of learning and ICT projects, and should be informed by the other challenges. Planning, implementing and maintaining the technology aspects of any initiative are essential for success, but they are not sufficient to ensure it. These decisions and actions are daunting to be sure, particularly for institutions without technical expertise, and particularly in the challenging operational context of many developing world nations. On the other hand, they do have a more direct method of resolution than many of the aforementioned institutional, political and financial barriers, particularly when supported by an effective organizational framework.

There are no one-size-fits-all answers in development or learning, and their interaction is no different. The cases presented and questions posed in this module are not intended to represent correct approaches, but rather to stimulate discussion and debate, informed by the unique and varied experiences of the diverse BOLD participants. As much as anything, the goal should be to ask the right questions, exploring what may intuitively seem right, and cross-pollinating experiences from different regions and approaches.

The following four case studies offer a very limited sample of projects that seek to enhance learning using ICT’s. They are not presented as being model projects, but rather to spark a dialogue on some of the many issues surrounding integrating ICTs into learning. The summaries are by no means complete (our apologies for any inaccuracies). For a more detailed description of each project we encourage you to consult the additional resources and links listed below each summary. Shorter descriptions of additional case studies can also be found at the end of this module.

NIIT Hole in the Wall Project:

NIIT, a leading computer software, services and training company headquartered in New Delhi, India, decided to conduct an experiment in what founder Sugata Mitra calls “minimally invasive education”. They installed an outdoor kiosk with a basic computer, Internet access and “touch pad” pointing device that is accessible from outside the boundary wall of their office, which borders a New Delhi slum. The kiosk was turned on without any announcement or instruction, and built in such a way that only children could use it comfortably. A video camera was placed on a tree near the kiosk in order to record activity near the kiosk. Activity on the CPU was monitored from another PC on the network. The statistics that were collected ranged from how much each application was used, to the number of times the system was shut down, to popularity of websites and number of short-cuts created. Follow-up interviews were conducted by NIIT staff after the initial observations were made and conclusions drawn.

NIIT photo from http://www.ncl.ac.uk/egwest/holeinthewall.html

Curious children (mostly aged 5-16) quickly investigated the kiosk and within days were found to begin basic operations including browsing the Web and painting without instruction, despite the fact that the software was in a foreign language (English, rather than Hindi). Children formed impromptu classes, introduced their own vocabulary (“needle” for the cursor, “channels” for websites), and learned other operations possible with only a touch pad (short cuts, cutting and pasting, folder creation) within one month. Adults were not personally interested in the kiosk, but did believe that it was valuable for the children. The experiment was repeated in other settings with similar results: despite lack of training, not necessarily intuitive software, and language barriers, children indeed rapidly maximized their basic understanding of the computer.

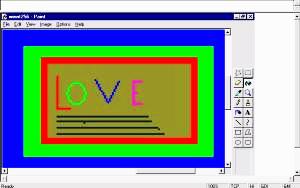

NIIT screenshot from http://www.ncl.ac.uk/egwest/holeinthewall.html

“Everyone agrees that today's children must be computer-literate. If computer literacy is defined as turning a computer on and off and doing the basic functions, then this method allows that kind of computer literacy to be achieved with no formal instruction. Therefore any formal instruction for that kind of education is a waste of time and money. You can use that time and money to have a teacher teach something else that children cannot learn on their own.”

– Dr. Sugata Mitra, Founder of NIIT Hole in the Wall Project

Video:

A video detailing the project can be found here.

Issues for you to consider:

Suppose you are a curmudgeon skeptic who sees nothing much in this description

but that kids with nothing better to do can learn to play video games.

What questions would you ask to test the value of this? What is the minimal

proposition that it demonstrates? What propositions is the story of these

"experiments" offered to demonstrate? What undocumented propositions

would have to be true to connect the evidence offered by the story to

the establishment of positive conclusions about Internet education?

Supplementary Reading

Site about the project

Article,

including interview with Sugata Mitra

Some background

information and history

Additional

information about some of the experiments

World Links is a global learning network linking thousands of students and teachers around the world via the Internet for collaborative projects and integration of technology into learning. The program works with schools, helping them to get online, and to prepare their teachers and curricula to use ICT to improve teaching and learning, largely through its training program. The program is now in over 20 developing countries across Africa, Asia and Latin America. One of the core elements of the World Links approach is collaborative project-based learning, with approximately 200,000 students and teachers in these countries having used the Internet to work with partners in over 20 industrialized countries. An estimated ninety-eight percent of all World Links schools connected during the past four years remain up and running. World Links attributes this high success rate to a strategic approach involving Ministries of Education, schools, parents and private sector partners.

The most significant constraints to date for the program have been in

the area of building a sustainable funding model, both in terms of the

non-profit organization’s costs and those of the participating schools.

Schools are responsible for a variety of significant start-up and ongoing

costs, while World Links must cover its own operating costs. The model

is ever evolving, but relies heavily on hard-to-get and potentially fickle

donor funding. World Links has had notable success developing a community

telecenter model, where computer labs are opened to the community outside

of school hours for fee-based usage. This arrangement covers the operating

expenses of the learning center, while enabling non-school users to take

advantage of the technological infrastructure. Funding, however, remains

a barrier to entry for many interested participants, and a barrier to

expansion for World Links.

Adapted from: http://www.world-links.org/english/html/about.html

Issues for you to consider:

Compare and contrast this project with CDI. Note the differences in the distributed governance structure, the idea of social franchising, the choice to operate independent of existing educational institutions (particularly given all the institutional, political, and financial barriers common to the education establishment and government), the insistence on each school being self-sustaining, and more demand driven approaches to learning.

Supplementary Reading

Project home page (in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese):

Computer Labs in Public High Schools: The Dominican Republic

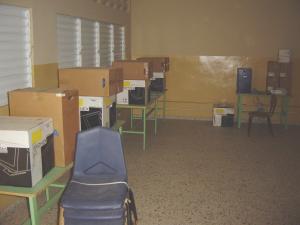

Starting around 1997, the Dominican Republic began the installation of computer labs in hundreds of high schools throughout the country. Each was equipped with 20 networked computers, productivity software and a VSAT (Very Small Aperture Terminal) Internet connection. The goals of the project were not simply to provide connectivity and hardware, but rather to provide a tool to facilitate learning in different subject areas to every high school, regardless of its location.

In spite of some major setbacks including inadequate or no electricity in some areas, limited community participation (and little or no preparation for the host school), and assorted technical difficulties, the effort succeeded in supplying labs to virtually every high school in the nation. In doing so, it has in many areas provided a resource not only for students but also for community members. And while this is certainly impressive, there remain many areas for improvement, particularly in the area of teacher training and use of the labs for educational purposes.

The unstructured access periods are dominated by chat, games, and surfing, while integration in the curriculum is greatest in the subject areas of natural and social sciences, mathematics and Spanish language (according to a lab supervisor survey). And although integration overall in the curriculum was lower than hoped and educational content is still lacking, educators reported that student interest in their studies increased prominently.

The response and overall experience has been quite varied across schools, however, with some computers still boxed-up and collecting dust more than four years after of launching the project. Although encouraged to remain open outside of school hours, most labs are closed after school and on weekends, as well as during the summer holidays. Operating costs are significant and ongoing financing of the labs remains an unsolved challenge. Critics argue the project is a failure, while supporters respond that although they have had difficulties, they succeeded in installing thousands of computers with Internet connections across the country, thus offering the nation’s high school students access to new technologies that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive.

Issues for you to consider:

What might have led the government to success in distributing and networking the computers, but to less positive results in other elements of the program? Why might some of the computers have remained in boxes even though many of the technical issues were resolved? Are there ways that school and community involvement could help address some of the barriers this project has encountered, particularly in terms of financial sustainability? What sort of things would need to happen in order to leverage that support?

Supplementary Reading:

This report was completed in October 2002 and contains an analysis of the use of ICT’s in the Dominican public education system in the introduction and Chapter 1.

Country

Profile from the 2001-2002 Global Information Technology Report

Jamaica Computer-Based Education Project: Drawing Youth into Technology through Creative Expression

The Berkman Center began doing research into information technology education projects in Jamaica in 1996. In January 2003, it launched a computer-based learning pilot project in Jamaica’s schools in co-operation with the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Technology and other local organizations. The main goal of the project is to draw youth into technology through creative expression, spurring the production of local (audio and visual) media and encouraging the development of new representations of self and community.

The project is very small-scale, supported by two Berkman affiliates in Kingston and a modest budget. It works entirely within schools that have functioning (possibly underutilized) computer labs, prioritizing expansion to as many interested schools as possible in the near term, and continuation and expansion as appropriate.

The project’s premise is that making computer-based learning fun

for students is the key to drawing them into exploring the possibilities

of computer and Internet technology. The hook is digital music, created

with software in an intuitive graphical representation that allows introduction

of local sounds as sharing between composers (more on Fruity

Loops in this audio

clip). In the big picture, the aim is to help Jamaica's schools create

a network of websites with student-produced content, from music created

in the program (Kingston

page), to school newsletters, and other media. Three schools and one

community center are currently involved (St.

Andrew High School for Girls, Camper Down High School, Tivoli

Gardens High School, and Denham

Town Community Skills Training Project), with ongoing efforts to include

others, as well as one prison.

The project does not yet include any formal evaluation component. Preliminary

success has occurred in schools where a particular teacher in the school

has had the initiative to help bring the program in and find time for

it in the school curriculum. One of the greatest difficulties has been

getting beyond verbal cooperation on the part of the government. Other

major challenges include difficulties with hardware and operating systems

in school labs, lack of student access to the Internet, slow and expensive

Internet connections, lack of time on the part of overworked/underpaid

teachers for training, and insufficient time and money to shepherd the

project until it can stand on its own.

Interviews and Audio:

Interviews

conducted with students and program administrators

For discussion on the objectives of the project, please click here: audio

clip

For an example of the use of this software in a school in Cambridge, USA,

please click here: audio

clip

Issues for you to consider:

What are the key elements that differentiate this approach from more traditional ICT and education interventions, and what implications might they have for success? How should we evaluate its “success”? What might the appropriate metrics be?

Additional Resources:

Homepage for the project, including

its blog (weblog), lesson samples, music samples

An

article about the use of digital music in education

Some

background information about Jamaica and its broader ICT plans:

Country

Profile from the 2001-2002 Global Information Technology Report

Readiness

report for the network world – Jamaica assessment

The Way Forward- Human Resource Development Technology Driven Strategy for Jamaica

We have examined a few of the many ways in which computers and the Internet can be introduced into a learning environment. The aforementioned approaches differ in terms of content, form, implementation, scale, objectives, and so on. Let us now try to look at it in a slightly different manner, examining some of the ideas behind these initiatives, and attempting to draw lessons from them.

Rethinking

Learning in the Digital Age, Mitchel Resnick

In this article Resnick makes two main distinctions: one between information

and methods: ‘computers are wonderful for transmitting and accessing

information, but they are, more broadly, a new medium through which people

can create and express; a second one between access and technology fluency:

when thinking about the digital divide it is important to shrink the access

gap, but the fluency gap could remain. In view of these differences, there

is the need to rethink the way technologies are used in education. Rethink

when and where people learn, and consider whether educational reforms

should take place, and how.

Audio clip on fun tools in schools

Complexities

and Challenges of Integrating Technology into the Curriculum, Joanne

Capper (Note: Free Registration Required)

This article looks at the question of whether to formally integrate technology

into the schools' curricula, particularly in primary and secondary education.

Arguments run both ways. Reasons not to include technology formally into

the curricula include: overly packed curricula, unequal or unreliable

access to the Internet, lack of teacher training, and technical difficulties.

Reasons to include it are: possibility to use technical resources in an

integrated manner, the fact that technology can be a powerful tool in

learning, and that it would be the best way to make the most of sometimes

underutilized costly investments. The article gives some examples of curriculum

areas that could gain with the introduction of technology to enhance children’s

learning.

Screen it Out and

Pass the Chalk, The Economist

These two articles question the effectiveness of teaching with computers.

They allude to a study performed in Israel that suggests computers may

not be an effective teaching tool, and asks whether there is excessive

enthusiasm about technology in teaching? Based on the study, the article

doubts the sense of preferring technology-enabled approaches over traditional

methods of teaching, especially face to face contact with teachers.

Does

This Stuff Work? A Review of Technology Used to Teach, J. D. Fletcher

(Note: Free Registration Required)

Fletcher analyzes the effectiveness and usefulness of technology in education.

The article talks about the necessary partnership between humans and technology

and the benefits in terms of individualization and interactivity. It also

looks at affordability of technical instruction and effectiveness.

Ten Lessons

for ICT and Education in the Developing World, Robert Hawkins

Hawkins offers practical insights on the how and why of introducing computers

and the Internet in education. Departing from experiences in the World

Links project (see case study above) Hawkins draws 10 lessons that should

be considered when setting up a project. He examines effectiveness, technical

sustainability and successful solutions, policy and institutional aspects,

training, financing, etc.

Issues for you to consider:

Looking at your own community, how do people perceive education –

how does it relate to personal and professional development of the individual

and the society? What sorts of individual and social investments does

it merit? Is any technology currently used to serve educational aims?

Is it generally viewed as a unique opportunity? What is the perceived

role and importance of technology and education?

The numerous and varied experiences with the integration of ICT and learning

suggest great promise as well as great challenges. As we move forward

and these technologies become more widely accessible and appropriate developing

world contexts, however, we will need to make decisions about how best

to adapt to these new tools and approaches, to learning and to each other.

Should technology adapt to fit the current dominant educational models?

Or should educational approaches be redesigned to fit better with these

technologies? Are some approaches better suited to certain kinds of communities?

Do you think it is likely that education will undergo significant change

over the next decade?

For H2O (above questions), please click here

For WebBoard (Case Study questions), please click here

Wrap-up: Panel discussion with case study representatives

As a wrap up and final part of the learning module, please join us on an online debate with Colin Maclay, Charles Nesson, and representatives from different case studies described above.

Representatives from NIIT (Sugata Mitra), Computer Labs in Schools/Dominican Republic (Mark Lopes) and Jamaica Computer based Education Project (Rebecca Nesson and Wayne Marshall) have already confirmed their participation!

The panel discussion will be on during Thursday and Friday (April 17th and 18th). You can go back and see how the debate is going at any time. You are also welcome to comment on what is being discussed and give your opinion – we would love to hear your opinions!

We hope you will enjoy it and find it useful!

Please view the panel discussion, located on WebBoard, by clicking

here. Once on WebBoard, click on "Special Event - Learning Panel

Discussion." Comments may be posted in the regular Learning folder.

In this section you will find some links to additional resources you may want to explore if you want to further pursue some of the topics discussed above. These are just a starting point.

From Unesco: http://www.unesco.org/bangkok/education/ict/, http://is.iite.ru/html/, on evaluation and indicators http://www.unesco.org/bangkok/education/ict/unesco_projects/JFIT/sitanalintro.htm

Extensive OECD case studies of ICT and Education in OECD countries

TechKnowLogia: Online magazine (free registration required) covering wide range of topics in ICT and Education:

General resource of IT and education

IMFundo - Partnerhsip for IT in Education, UK site. Contains some interesting articles

Some articles on Community Technology Centers (CDCs)

Book: ‘Technologies for Education: Potential, Parameters and Prospects’, Haddad, W.; Draxler, A.; prepared for UNESCO,

Organization that sends recycled computers to developing world educational institutions and education non-profits

Educational software: Click-a-tutor

ClickATutor is an educational software application that provides a variety of material on a wide range of different topics: from Aerodynamics, History, Mathematics, English Grammar, etc. The software is installed locally on each machine and uses a self-paced interactive methodology to support traditional classroom instruction. It is intended to be used by students, teachers and parents. An online tour is available here.

Issues for you to consider:

Since it is locally-installed software, the content is static and externally determined. In what ways might this be a problem and what alternatives can you suggest?

What are the advantages/disadvantages to this format? Even though it doesn’t take advantage of the Internet might this model serve as a step forward that might help teachers and students become more comfortable before accessing the Internet?

Additional Reading:

http://www.clickatutor.com/

Computer Clubhouses

Founded in 1993 by The Computer Museum (now part of the Museum of Science) in collaboration with the MIT Media Lab and millions in grant money, dozens of computer Clubhouses around the world provide a safe and creative after-school learning environment where children ages 10 to 18 from underserved communities work with adult mentors to explore their own ideas, develop skills, and build confidence in themselves through the use of technology. The clubhouses provide thousands of youth around the world with access to resources, skills, and experiences to help them succeed in their careers, contribute to their communities. One of the notions developed is one of ‘young entrepreneurs’. The children in the Clubhouse identify a problem or aspect in their community that they would like to look at, or change, and they work on it. The clubhouses work closely with adult mentors: students and professionals in fields such as art, science, education, and technology who share their experience and serve as role models. The project counts on Intel financial support.

Interviews and Audio:

If you want to listen to an explanation of the project you can listen

to this

audio clip

Issues for you to consider:

Do you have any ideas for a more robust funding model? What are the implications for scalability in this model with the current approach?

Additional Reading:

http://www.computerclubhouse.org/about1.htm

Mitchel Resnick’s Lifelong Kindergarden group at MIT

Recent paper on the computer clubhouse

Braille Language Laboratory

One interesting way ICTs are helping educate is through technologies that are targeted to specific challenges. One of those areas is for blind or otherwise disabled people. India installed a computer lab specifically dedicated to serving the needs of the blind. Set up in Ahmedabad, it uses a "talking keyboard" connected to a Braille printer that allows students to both hear and read what is being typed by the teacher. They currently have 10 Braille printers. The software works in any language and could thus be used in any region in the world.

Additional Reading:

Blind People’s

Association in India