Conference Overview and

Background:

Digital Media Distribution – Speedbumps Scenario

The advent of P2P: instant nostalgia or virtual riot?

For many, Napster was a miracle. Instant access to the music libraries of people across the country enabled a million moments of nostalgia as users found music that they hadn’t listened to in years, and often could find now only on voluminous TimeLife compilations.

Yet eventually, the nostalgia evolved into an atmosphere of widespread celebration among music consumers as they downloaded for free, unchecked by technological, legal or social impediments. It was as if the plate glass windows of the record stores were suddenly smashed and the cops and storeowners were helpless to stop looting. The equivalent of a riot ensued. The entire inventory of the music business lay open, available for the taking, and for the looters, taking it was fun. Downloading music on the P2P networks was slick, easy and free. Kids and grownups alike rushed online to share digital music files peer to peer, searching for what they wanted, finding it, loving it, reveling in the modernity of the method and sticking it to the man. Feeling prevailed that the record labels had it coming. For too long they had been gouging consumers, charging too much for CD's, forcing consumers to buy whole albums when all they wanted was a song. Sharing music was an act of rebellion and retribution. A generation of music consumers increasingly came to think of music as something you get rather than something you buy.

What will it take to recreate a culture where music is regarded as something you pay for?

The contours of this question are bounded by two opposing visions that lie at extremes, each difficult if not impossible to implement, and each with its respective disadvantages. At one extreme is total technological lockdown, brought about by creation of a "trusted" online environment from which digital products cannot escape without permission. Through a combination of hardware modification, software design, encryption, legal sanctions, and internationally coordinated law enforcement, this "trusted" environment would enable regimes of DRM to be established that permit total control of digital products in the online marketplace. Technology would prevent those receiving digital products from copying them in violation of the terms of receipt. This would enable purveyors of digital content to charge what the market will bear without concern for leakage to open free systems of distribution like p2p or sneaker-nets. Such total control describes Nirvana for Big Entertainment, not merely preserving but vastly expanding its market position. Control through technology would be more complete than that which the copyright system has offered in the past, rendering the existing copyright system irrelevant and allowing the industry to capture great value from the efficiencies of digital distribution.

But achievement of such a system faces huge technological and political obstacles. Its creation may be technologically impossible. Experience to date with SDMI suggests the difficultly of creating usable encryption that can't be broken. And somehow technology must be developed that is capable of plugging the "analog hole" – the capacity of users to make new digital recordings of music played from speakers and video from played from monitors or screens free of any DRM embedded in the original digital recording. Displacement of unrestricted machines by machines carrying "trusted" chips would require massive retooling. Implementation of encryption technologies powerful enough to protect digital works from unauthorized copying require relatively expensive equipment and significant processing to decrypt, which puts the interests of the consumer electronics industry in producing inexpensive equipment to sell to mass markets at odds with the interests of Big Entertainment. Many who understand open architecture to be fundamental to innovation and freedom will oppose such change.

At the other extreme from total lockdown is total open sharing -- elimination of all the constraints of copyright law, creativity no longer supported by copyright but by an alternative compensation system (ACS) paid for by taxation. The ACS approach would eliminate the transactional base of the present copyright system and legitimate free distribution of all digital entertainment products. Creators would register their digital entertainment products and be paid by a government agency according to consumer usage with money raised by taxation on the means of digital distribution. The system would be defined by legislative process and administered by a government agency. Those who espouse this system claim economic advantages for it over our existing IP system in terms of cost savings and avoidance of deadweight loss, plus advantages for "semiotic democracy" created by breaking the power of the big labels. They see defeat of the existing system of copyright as inevitable.

But, like the total lockdown approach, implementation of a tax and royalty system faces huge technical and political obstacles. No one has figured out how to count usage in a way that cannot be rigged, or how to assure that money raised by taxation actually gets paid out to creators instead of going to pay for military or medicare, or how to assure nondiscrimination among creators (from gospel to porn), or how to set the amount of tax over time, or how to handle allocation of royalty entitlements among creators of derivative works, or how to deal with international free-riders. And even if these problems could be solved, the end result would appear to be the establishment of an international mega-governmental agency with power of the purse over entertainment, which seems, at least to some, an outcome at least as distasteful as total lockdown.

Speedbumps

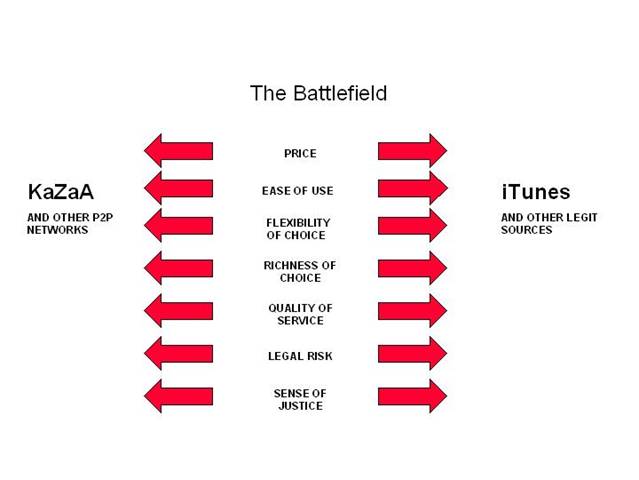

Our speedbump conference will explore a middle ground. Its goal is to help map the path to a viable online commercial marketplace for digital entertainment products without compromising the open end-to-end architecture of the Internet or decimating the existing transaction-based system of copyright. The speedbump approach conceives the field of play as a battleground on which victory will be judged not by total elimination of piracy but by attaining and maintaining a livable level of leakage from the legitimate commercial marketplace. Consider the following schematic:

This graphic pictures the entertainment industry as in a fight to establish a viable commercial online marketplace through a combination of (a) new business models that offer entertainment products on terms that no longer leave many people feeling like suckers, (b) tech impediments to unauthorized copying which, though not perfect, at least impose speed bumps sufficient to make illicit free file-sharing difficult for those who lack skill, time and determination, (c) legal risks credible enough to deter the timid and affirm the instincts of those who are normally law-abiding, and (d) public education designed to sensitize consumers to the viewpoint of artists who need to make a commercial return on what they produce.

The Balance

In many ways, the overarching question of instilling the social norm of purchasing music into a digital context resembles any attempt to persuade (or coerce) people to adhere to certain behaviors. The question becomes finding the right balance of carrot and stick. Arguably, no approach can successfully prevent every instance of transgression; but there is every reason to expect that the right balance of restrictions and incentives will dissuade all but the most dedicated infringers.

In a digital media context, consumers of digital entertainment who are willing to take the legal risk of illegal copying and who have the skill and willingness to spend the time will be able to get their entertainment products free, but this leakage from the commercial marketplace, if limited, can be tolerable, much as is the case in the software industry. Indeed, it some ways limited leakage is positive. Because commercial avenues of distribution must compete with free file-sharing in order to keep leakage limited and maintain their market, there will be continuing pressure to keep prices low and flexibility liberal. A limited leakage model also offers a de facto market solution to the Eldred problem of copyright forever. Protecting a work from leakage to and proliferation on the open file-sharing networks will require continuing expenditure of resources. The economic justification for the expenditure of such resources will be most pronounced in the period immediately prior to and following the new release of a work when its commercial potential is highest, and will then decline. Once the work's potential for further commercial return is exceeded by the cost of protecting it, specific efforts to limit its free proliferation will cease.

The Mechanisms

In most respects, the end is clearer than the means. There are manifold mechanisms and considerations that will bear on the right balance of restrictions and incentives, but they can be grouped loosely into four spheres: business models, technology, litigation and legislation, and education and rehabilitation.

a) Business Models

The development of alternatives to P2P that offer a vast selection of digital media that is easy to access, minimally restricted, and sold at reasonable prices is well underway. Enterprises like iTunes, LAUNCHcast and Movielink are already offering content to consumers using this concept, and offering a viable alternative for people who want to legitimately access and/or purchase digital media online.

For background, see iTunes Green Paper, available at http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/media/uploads/53/GreenPaperiTunes0304.pdf, Derek Slater, Digital Music Store, available at http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/digitalmedia/Slater-The%20Digital%20Media%20Store.htm. For an economist's view of policymaking with DRM, see also Michael Einhorn, Digitization and Its Discontents, http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/digitalmedia/einhorn.htm. The two key parameters for development of a truly successful and long-lasting business model seem to be richness of choice and price. Are content creators and distributors willing to offer content to legitimate digital distributors at a reduced profit margin if it contributes to shifting the culture of digital media consumption from infringement to legitimacy? What level of DRM will provide for flexibility and ease of use while still impeding widespread distribution? Can the digital media industries live with limited leakage? If so, how much?

b) Technology

Technological impediments to infringement are being used sporadically and some argue that their efficacy and even legality is questionable. See Edward W. Felten, DRM, and the First Rule of Security Analysis, available at http://www.freedom-to-tinker.com/archives/000317.html. See also Slater, supra. Traditional tort doctrines like self-help, self-defense, necessity and nuisance can arguably be analogized to provide a safe harbor for copyright owners to protect their property, but whether they would actually justify many of the more invasive techniques remains to be seen. See Curtis Karnow, Launch on Warning, available at http://islandia.law.yale.edu/isp/digital%20cops/papers/karnow_newcops.pdf; Orin S. Kerr, Cybercrime’s Scope: Interpreting “Access” and “Authorization” in Computer Misuse Statutes, excerpt available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=399740. What specific measures should NOT be permitted by content owners to protect their property? If it is assumed that it is reasonable for content owners to be able to do something to protect their property, then what should the parameters of that something be? Not crossing the boundary into a user's computer? Not compromising the privacy of the user? What are the specific values that should be protected in cyberspace when copyright owners employ technological self-help measures?

Spoofing, interdiction, watermarking and the like are tempting strategies, but they require significant time, energy and capital to implement, making them infeasible or inefficient for all but new releases of mass marketed media. A coordinated system of “totalitarian” DRM would seem less labor-intensive from an enforcement perspective, but developing even the most sophisticated and impregnable encryption will not make total DRM possible. See Edward W. Felten, Why Unbreakable Codes Don’t Make Unbreakable DRM, available at http://www.freedom-to-tinker.com/archives/000214.html. Furthermore, the more totalitarian the DRM regime, the less ease-of-use and flexibility is provided to the consumer, arguably eviscerating one of the “incentives” of legitimate purchase. And finally, there is always the problem of the “analog hole.” Is “totalitarian” DRM worth the massive effort and loss of consumer incentive if the analog hole cannot be plugged?

c) Litigation and Legislation

In September, 2003, members of the RIAA began a series of coordinated waves of litigation against individuals accused of downloading, distributing and/or making available for distribution, copyrighted files owned or licensed by record labels. The total number of cases filed is now over 1500, and while many of them have settled, the remaining cases will unquestionably result in a strain on an already-overloaded federal judiciary. For background, see EFF, RIAA v. The People, available at http://www.eff.org/IP/P2P/riaa-v-thepeople.php; IFPI, Recording Industry Starts Legal Actions Against Illegal File-Sharing Internationally, available at http://www.ifpi.org/site-content/press/20040330.html. Yet civil litigation is clearly more of an exemplary strategy, seeking to deter would-be infringers by making good on the threat of litigation, than any kind of cost-effective strategy for recovering damages caused by infringement.

Should the record companies be forced to take the initiative to enforce their federally-granted rights? Or should federal law enforcement agencies assume much of the burden of proceeding against massive, widespread infringement? See Terry Fisher excerpt, available at http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/digitalmedia/Fisher%20Chap4%20excerpt.htm. Recent legislation underscores this latter approach with the recent introduction of two new bills, H.R. 4077 and S. 2237, authorizing Federal law enforcement agencies to enforce copyright laws, both criminally and civilly. See H.R. 4077, 108th Congress. (2004) available at http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/media/uploads/72/9/HR4077.pdf; S. 2237, 108th Congress (2004) available at http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=108_cong_bills&docid=f:s2237is.txt. How effective is civil litigation as a deterrent? Is criminal enforcement appropriate for the masses?

Finally, courts in the U.S. and abroad have not always been sympathetic to the RIAA’s efforts at civil enforcement of their rights under copyright, and have brought privacy issues to the fore. See RIAA v. Verizon, 351 F.3d 1229, available at http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/digitalmedia/Verizon_Internet_Services_.htm; CRIA v. Doe, 2004 FC 488, available at http://www.fct-cf.gc.ca/bulletins/whatsnew/T-292-04.pdf. Even while the DMCA provides a limited safe harbor for ISPs as an incentive to self-police for infringement and terminate access to infringers, some ISPs are resisting mightily. Should some of the time/effort/cost burden be shifted to ISPs as enablers of infringing activity, whether or not they are aware of it? Should ISP's cooperate with entertainment industry efforts to curb online infringement is the ISP is not required to foot the bill? Do university ISPs have significantly different incentives to cooperate? Stated generally, what responsibility for infringement should the ISPs bear?

d) Education and social considerations

Universities present a special case. As institutions of higher learning, many feel an obligation to instill appropriate attitudes towards infringement in their students. See Graham B. Spanier, The Moral Imperative for Stopping Music Piracy, available at http://www.psu.edu/ur/GSpanier/oped/filesharing_111803.html; Graham B. Spanier, The Digital Piracy Dilemma, available at http://www.psu.edu/ur/GSpanier/speeches/digitalpiracy_030204.html. And the stakes are especially high. Under the safe harbor provisions of the DMCA, a university might be obliged to terminate access for a repeat offender. In the university context, the impact on a student’s educational experience of precluding internet access would be draconian.

The recording industry associations have also developed public awareness campaigns intended to increase public awareness of the illegality of infringement. See IFPI, Fact Sheet on Public Awareness Campaigns, available at http://www.ifpi.org/site-content/press/20040330i.html. Arguably, however, awareness alone is not enough; some sort of stigmatization is also required. See Lior Jacob Strahilevitz, Charismatic Code, Social Norms and the Emergence of Cooperation on the File-Swapping Networks, excerpt available at http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/digitalmedia/strelivutz-clip.htm. While it is unquestionable that education and public awareness are key pieces of an overall strategy to effect cultural change, could they be effective without litigation or criminal liability?

Conclusion

P2P does not have to be obliterated in order to limit infringement. Totalitarian DRM and Alternative Compensation Systems define the outer bounds of solution. Speedbumps offers a middle path. The battle against unconstrained infringement is not lost. The open terrain of the net offers some advantage to the forces of protection because infringers can be seen, and the more the infringers act to hide their activities, the more clumsy, skill-demanding and time-consuming their infringing activities become. The battlefield will be dynamic over time. Every move may elicit a countermove, but each time that happens, the forces of protection can gain ground. Some say P2P means DRM is DOA, but this assumes that protection technologies are worthless if they can be broken. CSS proves this is wrong. It's a battle for hearts and minds of consumers and casual downloaders in which no serious effort has yet been made to identify the "bad guys" and the "good guys". The real bad guys are the folks who leak music from studios, who rip music from CD's, and who make huge amounts of commercially viable copyrighted material available for free download. The good guys are the artists who would like to be able to make a dollar from their new releases. With coordinated efforts and a balanced approach, a culture supportive of a vibrant legitimate online marketplace can be developed and maintained.